The Arts Apply to Illness Best

Some people use the terms “disease,” “illness,” and “sickness” interchangeably, and perhaps this is to be expected given that traditional sources refer to one or the other to define the rest of them. These terms can be distinguished among themselves, however, and distinguishing them is essential to applying the Arts where they are most relevant and useful to people with health problems and to people who are interested in the Arts for various reasons.

Here’s the distinction I use:

lllness is what people experience as something distinct from the disease that can cause a health problem and as something distinct from the sickness society may recognize as a health problem. And, it is the illness distinction where the Arts can be applied to best effect, while Biomedicine is best applied to disease distinctions, and societal and cultural responses are best applied to sickness distinctions. My project hinges on being able to distinguish the illness experience as conceived by the person with a health problem from disease as conceived by Biomedicine and from sickness as conceived by Society.

Here’s my argument for this distinction:

We can take a position that disease, illness, and sickness are distinguishable from one another because each of them is an independent entity with clear borders and that exist in nature. Or, we can take a position that distinctions among disease, illness, and sickness derive from contextual factors comprising, as Rosenberg identified, “artifacts of a particular moment in time and of particular institutions and intellectual developments.” (p. 496) As such, disease, illness, and sickness are each socially constructed to some degree as are the distinctions among them. By using a contextual approach in making these distinctions, disease, illness, and sickness become more useful as heuristic tools to describe and explain health problems. The Arts, as products applicable to the illness experience, are created by people who generally understand and react to disease, illness, and sickness more as cultural artifacts than as natural phenomena. Therefore, I will evaluate the distinctions that have been made among disease, illness, and sickness that draw from contextual analyses because these distinctions will align better with the Humanities genres that can address them.

Here’s some scholarly work in support of my approach:

I. Some theory:

Although the distinctions among disease, illness, and sickness had been the subject of theoretical debate since the 1950s, Andrew Twadell in 1967, and Marshal Marinker in 1975, made some of the first attempts to make these distinctions relevant to contemporary health care. Both of them chose to use definitions for disease, illness, and sickness as a way to distinguish each from one another, and the definitions they used refer to some notion of health. Twadell defined disease, illness, and sickness as follows:

Disease is a health problem that consists of a physiological malfunction that results in an actual or potential reduction in physical capacities and/or a reduced life expectancy… Illness is a subjectively interpreted undesirable state of health. It consists of subjective feeling states (e.g., pain, weakness), perceptions of the adequacy of their bodily functioning, and/or, feelings of competence…Sickness is a social identity. It is the poor health or the health problems(s) of an individual defined by others with reference to the social activity of that individual.

Quoted in Hofmann, pp. 652-653

Marinker defines disease, illness, and sickness, but he refers to them collectively as “three different modes of unhealth.” (p. 82) His disease is a “pathological process” that can be discerned or sensed in some objective way through, for example, seeing or measuring. The cancerous tumor can be seen, the amount of blood pumped by the failing heart can be measured. Alas, while putting an emphasis on the objective nature of the disease distinction, Marinker recognizes that what constitutes a disease often represents just some degree of variation from a biological norm. Discerning the degree of variation from a biological norm is tricky business. Getting to what is normal, as Canguilhem advises, “is to know within what range of oscillations around a purely theoretical average value individuals will be considered normal.” (p. 154)

In contrast, Marinker’s illness mode is what a person experiences when in “unhealth,” and as such these experiences are subjective and personal. Thus, people manifest illness through subjective descriptions such as “I feel poorly,” “my head hurts,” or “I don’t feel right.” Marinker’s sickness mode is what is sanctioned socially as “unhealth.” Societies and its social institutions have a stake in what is considered disease and what is considered illness, and when they recognize a person’s disease or illness, they say that person is sick or is experiencing sickness.

Twadell and Marinker thus distinguish disease, illness, and sickness by trying to use straightforward definitions that circumscribe disease as the pathological element of health problems, illness as the subjective experience of health problems, and sickness as the social sanctioning of particular health problems. Would that it were so simple.

Others have elaborated on Twadell’s and Marinker’s definitions of disease, illness, and sickness. Arthur Kleinman also considers illness as the subjective experience of health problems, but he does not confine illness to just the person directly affected by a health problem. In his view, illness is also the experience of people who are affected by the health problems of a particular person, such as family members, friends, and colleagues. He characterizes the illness experience as not only what people may feel in the way of symptoms such as a headache or back pain, but also as the consequences of them such as missing work or school, and the emotional responses such as anger and frustration.

Kleinman further distinguishes disease from illness more as a matter of perspective than as a matter of different modes or phenomena. The physician working within the biomedical model reduces the illness experiences of people to technical concepts that are categorized as recognized disease states. And so disease to Kleinman becomes the physician’s perspective on the experiences people present. Additionally, the perspective physicians take are affected by their particular training, practice, and interests. What the rheumatologist may call fibromyalgia the gastroenterologist may call irritable bowel syndrome. Like Twadell and Marinker, Kleinman distinguishes sickness as the health problems recognized by social and cultural forces, but he also allows that sickness can reflect social problems within particular populations as well as the health problems of particular people. As an example, he describes how tuberculosis can be recognized by a society as a health problem for individuals, but it can also be an indicator of poverty and malnutrition amongst certain groups of people.

Bjørn Hofmann also sees the distinctions among disease, illness, and sickness as a matter of perspective in a way that is similar to Kleinman but more refined. Hofmann says that disease, illness, and sickness are just the three ways that particular health problems are seen in contemporary Western societies. Disease represents a biological perspective, illness represents the phenomenological perspective, and sickness represents the behavioral perspective. It follows, then, that the disease perspective motivates health care professionals and institutions to treat or cure the health problem; the illness perspective causes people to recognize and respond to their health problem; and the sickness perspective results in decisions to assign the sick role status and corresponding rights and support for a particular health problem. However, lest we think that every health problem can produce these three perspectives, Hofmann is quick to tell us that this is not so. Health problems can indeed produce all three perspectives, but health problems can also produce only one of the perspectives or any combination of two of them (vide infra).

Eric Cassell sees disease and illness as different entities, but not because they are necessarily different phenomena or as a matter of perspective, but rather as an imperative. The imperative derives from what people experience apart from the pathophysiological elements of health problems. What people experience can be common across many health problems, and many of these experiences are not sufficiently addressed by those measures aimed at the pathophysiological aspects of particular health problems. Therefore, it becomes imperative to distinguish disease and illness so that physicians and other health care professionals can take the illness experience into account when helping people. Cassell refers to actions aimed at disease as curing and actions aimed at the illness experience as healing. Based on this notion, health care professionals who do not distinguish disease from illness may cure a disease but not heal the patient. Unlike other authors, Cassell does not distinguish sickness from disease and illness as the social sanctioning of health problems. He sees sickness as another dimension of disease and illness based on the severity of the consequences. A person can have a disease or be experiencing illness, but they are sick when their life is threatened or their way of life is substantially altered. In his most prosaic formulation, he says, “let us use the word ‘illness’ to stand for what the patient feels when he goes to the doctor and ‘disease’ for what he has on the way home from the doctor’s office.” (p. 48)

To Judy Segal, the distinction between disease and illness is based on the different ways they are established. Disease is determined by “positive objective tests.” Illness, on the other hand, is a matter of argumentation, i.e., illness is what the ill person can persuade other people to agree what illness is. People with migraine must persuade their physicians that they are not migraine-type people but rather that they suffer from migraine symptoms. People with constellations of malaise, exhaustion, depression, and joint pain must persuade others that they suffer from fibromyalgia. Negotiations may ensue when others are not in agreement with people who argue that they are ill. Similarly, sickness can be distinguished by the success or failure of the arguments people make towards social recognition. Further, illness as argumentation accentuates the distinction between illness and disease because as an argument the process of determining illness can accommodate more and varied inputs, as described by Viesca:

Illnesses, as classified items, exist only in specific historical and cultural contexts and are always expressed in particular languages, in concrete situations wherein it’s possible to recognize the confluence of cognitive factors, systems of cultural representations, mythical beliefs, identity and difference relationships, social relationship nets, all factors defining individual characteristics needed for the illness systems and particular illnesses construction.

p. 31

In contrast, at least for last two-hundred years, Biomedicine limited what could be used to determine disease to inputs that are biological and nontemporal. Appendicitis results from a rotting appendix now as it has for the last two centuries. Argumentation is a part of determining disease as well because the arguments about disease can involve social and culture dimensions, but the arguments are centered more on interpretation of biological inputs.

Whether the distinctions among disease, illness, and sickness are understood as a matter of definitions, modes, perspectives, imperatives, arguments, or aphorisms, the question is whether these distinctions are useful for our endeavor on this site. And indeed they are especially useful when seen as the “triad” Hofmann describes.

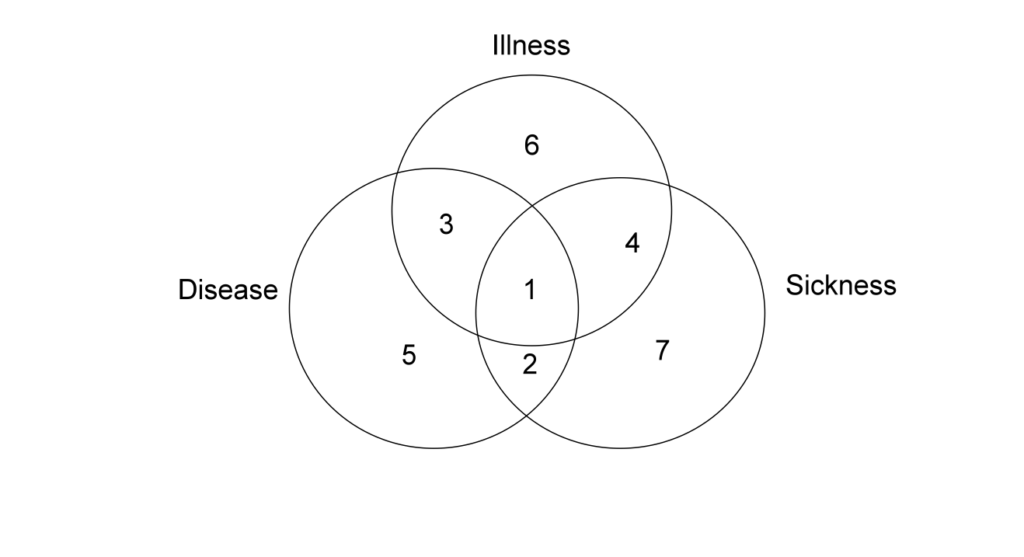

Hofmann describes how a health problem can be seen only as illness, with sickness, with disease, or with both sickness and disease (see figure below). For example, illness stands alone for people who manifest a variety of symptoms such as pain, fatigue, numbness, and general discomfort for which there can be no pathological basis found, and which do not aggregate into recognized entities considered as sicknesses in society. These situations have been called “medically unexplained symptoms (MUS),” “functional symptoms,” “non-organic illness,” “conversion,” “somatization,” “abnormal illness behavior,” “factitious,” “hysterical hypochondriacal,” “psychosomatic,” and “illness idioms.”

Problems such as the common cold and tooth decay are examples of conditions where a person can conceive a health problem for which there is a pathological basis but society does not consider them health problems that rise to the level of sickness.

Fibromyalgia is an example of a health problem that produces illness and sickness because people who have it experience a specific set of symptoms and society has given it the status of sickness through payment for treatment and approval of drugs for it; however, a pathological basis for it remains elusive and so it is not considered a disease.

Migraine represents an example of illness with both sickness and disease because of the discernible symptoms that people conceive as illness, the pathological basis attributed to neurovascular mechanisms, and the societal recognition of it through payment for treatment and time off, and the approval of drugs for clinical management.

Note: The numbers refer to how specific health problems can be associated with disease, illness, and sickness as follows:

1 = Disease, illness, and sickness

2 = Disease and sickness

3 = Disease and illness

4 = Illness and sickness

5 = Disease

6 = Illness

7 = Sickness

This framework can inform the selection of Humanities works for particular people. People with illnesses that are not associated with diseases or sicknesses, for example, will feel particularly isolated and disenfranchised, as represented by number 6 in the figure. As Nettleton et al. characterize this scenario, “they are adrift and they have to live with and make sense of their chaos.” People in these situations have been called “medical orphans.” They are challenged to find meanings to their illness because there is no disease or sickness concepts they can use, for example, how the illness progress, how the illness interferes with life in any serious way for any substantial period of time, or how the illness may diminish social status, position, and support. Theirs is a chaos narrative, and thus humanities content could be selected that shows them an alternative narrative, a narrative that helps them see their illness as part of their humanity and how that realization can lead them to more ordered understandings of their situation.

People with illnesses associated with disease or sickness, as represented by number 3 and number 4, respectively in the figure , may find understanding their situation less challenging because Biomedicine or Society has provided some level of explanation for it. Nonetheless, even with an associated disease or sickness, the illness experience is still one that is often accompanied by a feeling of bewilderment and abandonment. People with illness and disease may feel aggrieved because their plight is not recognized nor supported by Society, while people with illness and sickness may feel legitimized but frustrated by the absence of a concrete biological explanation (and the haunting of the possibility that it’s all in their head (https://www.accordingtothearts.com/2019/07/23/is-it-all-in-your-head/). In choosing humanities content for these people, however, the associated disease or sickness concepts provide a basis to build upon.

II. Some data

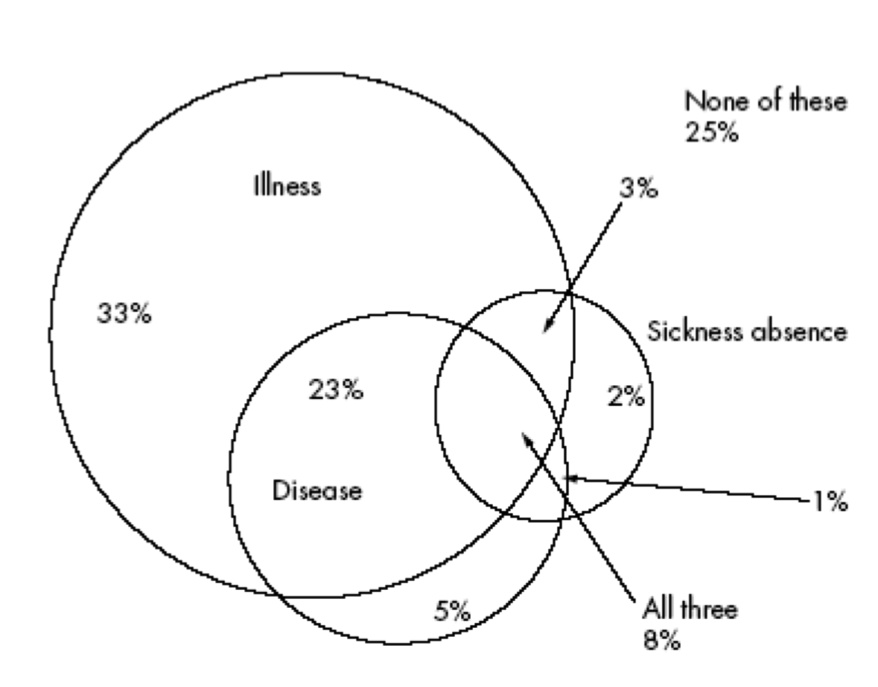

As intellectually appealing and persuasive as the distinctions among disease, illness, and sickness may be on theoretical grounds, the various theories offer little towards understanding whether people can actually be stratified by these distinctions. Knowing whether such stratification actually exists will inform my project with respect to what proportion of people claim illness in the manner the project is meant to address. Wikman, Marklund, and Alexanderson conducted an analysis involving a sample of the Swedish population in an attempt to do just that. These researchers used data from the Swedish Survey of Living Conditions, which has been conducted annually since 1974. About 7,000 people who are randomly selected are interviewed in their homes each year, of which about twenty percent have dropped from participation and have been replaced over the years from 1990 to 2005. For this study, survey data obtained from about 3,500 employed and self-employed people between the ages of sixteen and sixty-five during 1988 through 2001 were used. These researchers also used national registry data.

The analysis assigned people in the survey sample with illness based on survey questions about the existence of various symptoms such as pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances, and also based on the existence of various symptomatic conditions such as asthma and allergies. The researchers used the sick leave benefits registry to assign people in the survey with sickness, and they used disease codes as listed in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Ninth Revision (also know as ICD-9 codes) to assign people in the survey with disease. From these assignments, the researchers estimated the proportion of people who could be assigned with illness, disease, or sickness alone or in any combination.

The results support the theoretical assertions that disease, illness, and sickness can be distinguished, and that they are not always independent of one another, i.e., people can be assigned to only one or any combination of them, as shown in the figure below. Indeed, only twenty-five percent of the survey population could not be assigned at all. Conversely, only eight percent of the survey population could be assigned to the putative paradigmatic case of disease, illness, and sickness at the same time. In summary, the analysis shows that most people can be viewed as experiencing disease, illness, or sickness, or some combination of two of them

Our interest, however, concerns the proportion of people who can be assigned with illness, and how many of them are assigned illness alone and with either disease or sickness. The analysis assigned a third of the survey population with illness. Another quarter of the survey population was assigned disease and illness. When the survey population assigned with illness and sickness, and with illness, disease, and sickness, the analysis assigns a total of two-thirds of the survey proportion with illness. Age, sex, education, or socioeconomic status did not affect the finding of the analysis.

While the results of this analysis may have some methodological limitations, the survey population corresponds to the population my endeavor concerns, i.e., people with health problems with discernible illness experiences, and people based in countries and societies that have similar health care institutions and cultural views on disease, illness, and sickness.

Sources:

Charles E. Rosenberg, “What is Disease: In Memory of Owsei Temkin,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 77, no. 3 (2003).

Bjørn Hofmann, “On the Triad of Disease, Illness and Sickness.” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 27, no. 6 (2002)

Marshall Marinker, “Why Make People Patients,” Journal of Medical Ethics 1, no. 2 (1975).

Georges Canguilhem, The Normal and the Pathological, translated by Carolyn R. Fawcett (New York: Zone Books, 1991).

Arthur Kleinman, The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing & the Human Condition (New York: Basic Books, 1988).

Eric J. Cassell, The Healer’s Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976).

Judy Z. Segal, “Illness as Argumentation: A Prolegomenon to the Rhetorical Study of Contestable Complaints,” Health 11, no. 3 (2007).

Charles E. Rosenberg, “Framing Disease: Illness, Society, and History,” in Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History, eds. Charles E. Rosenberg and Janet Golden (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1992).

Carlos Viesca, “The Construction of Illness: A Context Problem,” in Life – Interpretation and the Sense of Illness within the Human Condition: Medicine and Philosophy in a Dialogue, eds. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka and Evandro Agazzi, 72 (Milan: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1998).

Ludwik Fleck, Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Translated by Fred Bradley and Thaddeus J. Trenn, eds. Thaddeus J. Trenn and Robert K. Merton (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981).

Sarah Nettleton, “’I Just Want Permission to be Ill’: Towards a Sociology of Medically Unexplained Symptoms,” Social Science & Medicine 62, no. 5 (2006): 1167-1169.

Sarah Nettleton, Lisa O’Malley, Ian Watt and Philip Duffey, “Enigmatic Illness: Narratives of Patients who Live with Medically Unexplained Symptoms,” Social Theory & Health 2 (2004): 63.

Howard Waitzkin and Holly Magana, “The Black Box in Somatization: Unexplained Physical Symptoms, Culture, and Narratives of Trauma,” Social Science & Medicine 45, no. 6 (1997): 811-825.

Merilee D. Karr, “The Moment of Death,” in The Healing Arts: An Oxford Illustrated Anthology, ed. R.S. Downee (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Anders Wikman, Staffan Marklund, and Kristina Alexanderson, “Illness, Disease, and Sickness Absence: An Empirical Test of Differences between Concepts of Ill Health,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59, no. 6 (2005): 450-454.

Note:

This post draws from an article I published: Journal of Healthcare, Science and the Humanities, 2012; 2(2): 56-73, and from my doctoral dissertation.