Playwright: Kenneth Lonergan

Director: Lila Neugebauer

Performance venue: John Golden Theater, New York, NY

Seen: January 26, 2019

Running time: 135 minutes

According to the Art:

The play endeavors to show the raw effects of mental deterioration on aging people and those who are connected to them without having to see them through the obscuring and distorting effects of medicalization. More is thus revealed about the family dynamics in these circumstances and about the robustness of the human spirit.

Synopsis:

The play is set between 1989 and 1991, the last two years of the life of Gladys Green, an eighty-five year old woman who runs a small art gallery in Greenwich Village, New York City. She lives on her own near the gallery, but she is watched over by an adoring grandson (Daniel) who lives in the same building, and by a doting daughter (Ellen) and son-in-law (Howard) who live uptown from her. Gladys can’t hear very well and she has diabetes, but otherwise she is doing well enough.

From this point we watch Gladys gradually lose some of her mental capabilities, mostly memory. Our attention is directed to how the family responds and comes to grips with her deterioration. Aware of Gladys’ past before she opened her gallery when she was an activist lawyer with a frenetic lifestyle, Daniel lays out a strategy the family adopts: “she’s got to have something to do.” Their chief tactic is to keep Gladys in the gallery where she could mix with people, keying off what she said keeps her sane: “Everyone needs someone to talk to, otherwise you’d just go nutty. I love to talk to people.”

This approach works for awhile, and mainly through permitting a young artist (Don) who has never before sold a painting to exhibit his work in the gallery. Don keeps her company and talks to her. Don thinks he notices Gladys’ hearing problems worsening, but Howard tells him, “I’m afraid that’s more her memory than her hearing aid.” What speeds up her deterioration, however, is the gallery losing its lease when the owner of the space decides to turn it into a cafe.

A path ensues that is familiar to many people who have been close to a person losing memory and other mental functions with age. The family desperately wants to keep Gladys as independent as possible, but they need more help as time passes. She can stay in her own apartment for awhile with visiting nurses and aides, but eventually she needs to move in with Ellen and Howard; they never liked the idea of putting her in a nursing home, and they never did. In an aside directed at the audience, Daniel describes what his mother did for Gladys thereafter: she “took care of her, dressed her and cleaned her up and fed her and watched her fall apart, day in and day out with nothing to stop it and no relief in sight.” It did end, though, two months later when Gladys died in Ellen’s home.

Analysis:

The focus of the play is more on Gladys’ family and how they handle her mental deterioration than on the particulars of her deterioration per se. We see how the family struggles to maintain their relationships with Gladys and among themselves. We see the emotional challenges families face in this situation, which range from anger to compassion and from frustration to concern, and sometimes all in the course of just a few minutes. But, the playwright, Kenneth Lonergan, may have had more in mind than just rendering family dynamics amidst an older family member losing her mind. He could be siding with the view that the deterioration of the mind in older people is a matter of aging and not disease.

As such, no attention is paid to the medical dimension of Gladys’ mental problems. The words “dementia” and “Alzheimer’s” are never uttered—only reviewers and blurb writers use them. No medical terminology enters any conversation about Glady’s mental status. No doctors are ever mentioned except when Gladys needs attention for her hearing, eyesight, and diabetes. No drugs for Alzheimer’s are prescribed. No clinical trials for promising experimental dementia treatments are sought.

To accentuate this view, Lonergan made both Ellen and Howard practicing psychiatrists, health care professionals who are involved in the medical management of dementias. He has Ellen say to Daniel at a particularly frustrating moment, “when I get senile just put a bullet through my head”—the word “senile” being associated with mental deterioration that can manifest as an ordinary consequence of aging. Another time Howard refers to older people “losing their marbles” as their mental abilities diminish with age, which is a more colloquial form of the term senile for most people. The family is following the advice King Lear’s daughter Goneril gave to those around her father: “But let his disposition have that scope/As dotage gives it,” rather than the advice treatment guidelines medical organizations prescribe.

Without the obscuring effects of medicalization, Lonergan is able to open up room to consider what may be at work in Gladys’ mental problems. One possibility is the haunting prospect that what appears to be a global deterioration of mental function is just a speech problem. This becomes apparent through a note Lonergan used to set up a scene.

While Gladys now has a lot of trouble finding the right words, she still knows exactly what she is trying to say, and still addresses herself directly to the others with the same dogged persistence. In other words, she is not lost in her own world, nor disconnected from the others, nor is she talking to herself. She at all times pressures them for answers, and when they ignore or placate her it drives her even harder to get a real response from them.

Perhaps more haunting yet, Ellen asks once, “I wonder what she thinks. If she thinks anything.”

Lonergan goes further than family dynamics, though. He goes to the resilience and robustness of the human spirit as the family demonstrates through its responses to challenge after challenge with grace and love, mostly, while knowing only more challenges will come. So that no one would miss this punchline, Lonergan gave Daniel these last lines of the play in an aside to the audience.

It’s not true that if you try hard enough you’ll prevail in the end. Because so many people try so hard, and they don’t prevail. But they keep trying. They keep struggling. And they love each other so much; it makes you think it must be worth a lot to be alive.

Also:

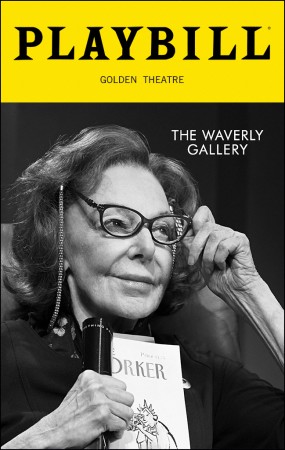

This review is based on the play as seen on Broadway in New York City January 26, 2019. This production featured Elaine May as Gladys, Joan Allen as Ellen, David Cromer as Howard, Lucas Hedges as Daniel, and Michael Cera as Don. The Waverly Gallery was originally staged at the Williamstown Theatre Festival in August 1999, and then Off-Broadway at the Promenade Theater from March 22 to May 15, 2000.

The play received two Tony Award nominations:

— Best Revival of a Play

— Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Play (Elaine May)

Grove Press (New York) has published the script in book form, copyright © 2000 by Kenneth Lonergan.

A version of this review is posted here at the NYU Literature, Arts and Medicine Database.