Iatrogenesis is a term, when applied narrowly, that describes the harm medical professionals or institutions inflict upon people while carrying out their responsibilities to help them. This narrow, but typical application of iatrogenesis may now be insufficient with the slow and steady institutional rearrangements and growing numbers and types of participants involved in affecting health care. A story Gabriel García Márquez set in the late 1700s, Of Love and Other Demons, centers on a young girl either infected with rabies or possessed by demons, points to a nonmedical source of iatrogenesis—the Church. That possible interpretation inspired me to consider expanding on the traditional sources of iatrogenesis.

How the Story Came to Be

Gabriel García Márquez was himself inspired to write Of Love and Other Demons as a cub reporter for a small-town newspaper in Columbia. He was assigned one day in October of 1949 to snoop around some goings on at the site of the “historic” Convent of Santa Clara that Clarissan nuns had operated up to a hundred years before when it became a hospital. Now it was being converted into a luxury hotel. The slowly collapsing roof over the course of those years caused damage where the chapel had been, and where the crypts of “three generations of bishops, and abbesses and other eminent personages” were buried. It became necessary, then, “to empty the crypts, transfer the remains to anyone who claimed them, and bury the rest in a common grave.” (p. 3)

Márquez watched the workers dissemble the crypts. In the case of one crypt in particular, he noticed that,

when the stone shattered at the first blow of the pickax, a stream of living hair the intense color of copper spilled out of the crypt. The foreman, with the help of the laborers, attempted to uncover all the hair, and the more of it they brought out, the longer and more abundant it seemed, until at last the final strands appeared still attached to the skull of a young girl…Spread out on the floor, the splendid hair measured twenty-two meters, eleven centimeters. (p. 4)

The only name legible on the stone was Sierva María de todos Los Ángeles. The foreman told Márquez that human hair continued to grow after death at a rate of “a centimeter a month,” so he figured the girl died about 200 years before.

What Márquez observed that day called to mind a story his grandmother once told him as a child about “a little twelve-year-old marquise with hair that trailed behind her like a bridal train, who had died of rabies caused by a dog bite and was venerated in the town along the Caribbean coast for the many miracles she had performed.” (p. 5) That tale, and what Márquez witnessed, became the basis for the book.

The Story

A twelve-year-old girl, Sierva María de todos Los Ángeles, lives in a seaport town in Columbia, South America. Her father, a marquis of diminishing wealth and influence, neglects her, and her mother hates and resents her. The people the marquis’ family has enslaved, who were mostly from different African countries, essentially raise Sierva María. She learns their languages, their dances, and their behaviors, which are all uncommon and considered erratic among people native to the area or who are there through colonization.

Sierva María is shopping at a marketplace with one of the enslaved workers when a presumably rabid dog bites her. But the location and superficial nature of the wound, and the amount of time that passes without clear evidence of rabies makes the chance it will ever manifest quite low. Nevertheless, when Sierva María develops a fever not thought related to rabies, the marquis brings in various sorts of health care practitioners of the day who put her through tortuous treatments that nearly kill her.

A young physician from Salamanca opened Sierva María’s closed wound and applied caustic poultices to draw out the rank humors. Another attempted to achieve the same end with leeches on her back. A barber-surgeon bathed the wound in her own urine, and another had her drink it. At the end of two weeks she has been subjected to two herbal baths and two emollient enemas a day, and was brought to the brink of death with potions of antimony and other concoctions…She had suffered everything: vertigo, convulsions, spasms, deliriums, looseness of the bowels and bladder, and she rolled up on the floor howling in pain and fury. Even the boldest healers left her to her fate, convinced she was mad or possessed by demons. (pp. 50-51)

Others also thought that if her erratic behaviors, which she often exhibited, were not due to rabies, then she must be possessed by demons. Not all priests consulted agreed, noting “that what seems demonic to us are the customs of the blacks, learned by the girl as a consequence of the neglected condition in which her parents kept her.” (p. 91) The local Catholic bishop and abbess were not persuaded, however, and convinced the marquis that Sierva María be incarcerated at the convent pending exorcism.

When time comes for the exorcism, the bishop is too infirmed and turns the case over to a thirty-six-year-old priest who serves as the bishop’s librarian. Father Cayetano Delaura is among those not convinced Sierva María is possessed, and has fallen in love with her during his visits to provide succor. The relationship becomes affectionate but chaste while plans are made for escape and marriage. When these clandestine meetings are discovered, Delaura is sent away, leaving a bereft Sierva María in the dark about his banishment and at the mercy of the bishop and the abbess.

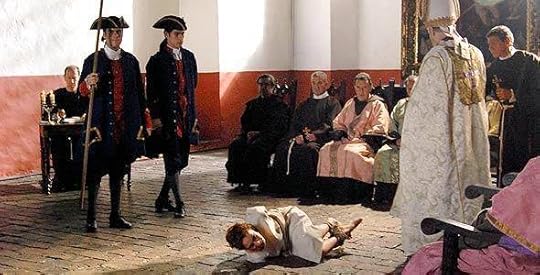

And so the ailing bishop commences the exorcism “with an energy that was inconceivable, given his condition and his age…Sierva María, confined in a straightjacket, her skull shaved by a razor, confronted him with satanic ferocity, speaking in tongues or the shrieks of infernal birds.” (p. 146) She battles each session with all she has despite her increasingly emaciated state from one session to the next. Then, ‘the warder who came in to prepare her for the sixth session of exorcism found her dead of love in her bed, her eyes radiant and her skin like that of a newborn baby. Strands of hair gushed like bubbles as they grew back on her shaved head.” (p. 147)

As Iatrogenesis Gently Creeps

Besides offering an interesting story, the book depicts the way interpretations of health problems and responses to them can get caught up in societal and cultural customs, traditions, beliefs, prejudices, doctrines, and dogmas among other factors. This story reveals how these factors can generate tension among societal and cultural institutions, in this case, medicine and religion, sometimes harming people as a result, and implicating institutions besides medicine, such as religion.

The dangers posed by activities meant to provide aid for people with health problems have always been recognized. Hippocrates, in his eponymous oath, constructed during the 5th century BC, instructs physicians on ways to avoid harming their patients. But not until 1924 when Eugene Bleuler connected the Greek word for physician or healer, “iatro,” with the Greek word for origin, “genesis,” to form “iatrogenesis,” was there a word for problems resulting from medical activities.

Ivan Illich, in 1976, expanded on the sources of iatrogenesis. He reserved the term, “clinical iatrogenesis” for harm resulting from professional health care activity directed at restoring health or preventing illness. To this distinction, he added “social iatrogenesis,” which he refers to as the harm societal arrangements for health care can cause, for example from hospitals and health care product industries. And, he added “cultural iatrogenesis,” which arises when societies yield to institutions, such as organized medicine, that dominate responses to individual and public health problems, pushing aside community responses that could be more nimble, more effective, and more compassionate. In making his case, Illich points to how “the siren of one ambulance can destroy Samaritan attitudes in a whole Chilean town.” Although Illich brings social and cultural dimensions to iatrogenesis, they still link directly to health care functions. In this novel, Marquez retrofits these forms of iatrogenesis as they could manifest in the late 18th century, colonized Columbia, and as they could apply to rabies, a serious and feared disease there at the time. But he also extends iatrogenesis beyond medical functions to encompass religious functions.

Sierva María experienced clinical iatrogenesis when her father, ignoring the principal physician, called in other practitioners when she spiked a fever (vide supra). Márquez allows that iatrogenesis was understood then conceptually when his narrator says of these medical people that many practiced in ways “the Inquisition had condemned…to a variety of punishments.” (p. 50)

The social and cultural iatrogenesis Márquez brings into the story shows how it extends beyond medical activities, in that the Catholic church takes an institutional role as a healer capable of doing Sierva María harm. Indeed, that possibility was known and her principal physician warned her father that since rabies was not a risk, “she, like so many others, would die of the cruelty of the exorcism.” (p. 115) Cultural iatrogenesis comes into Sierva María’s case through the Catholic Church’s domination made apparent by a widely-held sentiment, “that no one believed himself authorized to doubt [the Church’s position that] she was possessed by the demon” when no such consensus existed among individual medical and religious authorities. (p. 99)

Health care has changed a lot since Illich elaborated on iatrogenesis. Influences and determinants of health outcomes for individuals have expanded and grown, many of which create iatrogenic potential. Newer forms of practitioners and institutions take on primary roles as healers, or impose standards and behavioral expectations that can cause harm, making them conceivably accountable for iatrogenesis. The shift in health care delivery from individual practices to incorporated organizations (e.g., hospitals, physician offices, pharmacies, imaging centers) have brought business objectives and standardized methods into the care of individuals that can cause harm as well. As government agencies, religions, and movements are drawn into active involvement in the health of their constituents on grounds counter to accepted medical standards of practice generated by credible sources or legal and regulatory requirements, they elevate the risk of iatrogenesis and accrue accountability.

Other contemporary examples of iatrogenic creep most certainly exist. The combination of human progress and fallibility will ensure that it does, and at a rate faster than the time two centuries pass or twenty-two meters, eleven centimeters of hair grow post mortem.

Also:

Book citation:

Gabriel García Márquez (Edith Grossman, translator). Of Love and Other Demons, New York, Vintage International; 1995: 147 pages.

Of Love and Other Demons has been made into a movie (Del amor y otros demonios, 2009), and an opera.

Title painting:

St. Francis Borgia Helping a Dying Impenitent

Francisco Goya, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gabriel García Márquez is a winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (1982).

Edited by Lucy Bruell