Montaigne and his Essays:

Michel de Montaigne, born in 1533 into a wealthy family in the Bordeaux region of France is best known as the father or inventor of the essay. Stuart Hampshire, in his introduction to the Everyman’s Library collection of Montaigne’s essays, describes what Montaigne created as,

the loose, unstructured, discursive essay, replete with deliberate irrelevances, antiquarian references and classical quotations, with snippets of autobiography and fragments of philosophy and with speculations about the relations between mind and body. The final product, always and necessarily unfinished and open-ended, was to be the confused picture of its unique history.

p. xvii

Montaigne composed scores of essays over the course of several decades, off and on, while working in the Bordeaux municipal government, during an interregnum of his government service, and while serving as Mayor of Bordeaux and after. They were eventually compiled and published as a three-volume collection in 1588. He continued to add new essays and revise others up until the time of his death in 1592.

The primary subject of Montaigne’s essays is Montaigne: “What I write here is not my teaching, but my study; it is not a lesson for others, but for me.” (p. xxi) Among the topics he writes essays about are his health and infirmities. He has his share of infirmities, but kidney stones (“the stone”) seemingly plagued him the most. They caused him excruciating pain, and altered the way he lived. But Montaigne maintains he profited from kidney stones nevertheless, in the form of appreciation for the health he had and how he was able to get on with his life.

Montaigne held the medical professionals of his era in contempt. He resented how they threatened his time and agency, and feared how unreliable medical knowledge drove their decisions. Although health care has come a long way since he railed against what was available to him in the mid-1500s, Montaigne’s complaints bare some resemblance to those of today.

Here I excerpt some of Montaigne’s essays addressing his kidney stones. I divide the excerpts into those concerning acute events with kidney stones, those concerning living with the ever threat of an acute event with kidney stones; and those concerning how Montaigne, despite all he suffered from kidney stones, saw a benefit to them in certain ways. Most of what Montaigne has to say about kidney stones are found in his essays, Of the Resemblance of Children to Fathers and Of Experience.

Acute Kidney Stone Events:

Montaigne’s description of his acute kidney stone episodes corresponds to current-day, paradoxically dispassionate biomedical descriptions while adding an important dimension to what people go through with them. Here is a classic biomedical description of an acute kidney stone event.

From: Curhan GC. Nephrolithiasis. In: Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J. eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2022. Accessed March 01, 2024.

There are two common presentations for individuals with an acute stone event: renal colic and painless gross hematuria. Renal colic is a misnomer because pain typically does not subside completely; rather, it varies in intensity. When a stone moves into the ureter, the discomfort often begins with a sudden onset of unilateral flank pain.

The intensity of the pain can increase rapidly, and there are no alleviating factors. This pain, which is accompanied often by nausea and occasionally by vomiting, may radiate, depending on the location of the stone. If the stone lodges in the upper part of the ureter, pain may radiate anteriorly; if the stone is in the lower part of the ureter, pain can radiate to the ipsilateral testicle in men or the ipsilateral labium in women. Occasionally, a patient has gross hematuria without pain.

Although nephrolithiasis is rarely fatal, patients who have had renal colic report that it is the worst pain they have ever experienced.

Here are excerpts across the essays Montaigne included details of his acute kidney stone episodes and as compiled in The Complete Works published by Everyman’s Library (2003).

I am at grips with the worst of all maladies, the most sudden, the most painful, the most mortal, and the most irremediable. I have already experienced five or six very long and painful bouts of it…But the very impact of the pain has not such sharp and piercing bitterness as to drive a well-poised man to madness or despair.

p. 771

The obstinacy of my kidney stones, especially in the penis, has sometimes cast me into long retentions of urine, for three, even four days, and so far forward into death that it would have been madness to hope, or even to wish, to avoid it, in view of the cruel attacks that this condition brings. Oh what a grand master in the art of torture was that good Emperor (Tiberius) who had his criminals’ penises tied so they would die from not being able to piss!

p. 771

In such extreme accidents it is cruelty to require of us so composed a bearing. If we play a good game, it is a small matter that we make a bad face. If the body finds relief in complaining, let it do so. If it likes agitation, let it tumble and toss at its pleasure. If it thinks that the pain evaporates somewhat…for crying out more violently, or if that distracts its torment, let it shout right out. Let us not command this voice to come out, but permit it to.

pp. 699-700

I test myself in the thickest of the pain, and have always found that I was capable of speaking, thinking, and answering as sanely as at any other time, but not as steadily, being troubled and distracted by the pain.

p. 700

They see you sweat in agony, turn pale, turn red, tremble, vomit your very blood, suffer strange contractions and convulsions, sometimes shed great tears from your eyes, discharge thick, black, and frightful urine, or have it stopped up by some sharp rough stone that cruelly pricks and flays the neck of your penis; meanwhile keeping up conversation with your company with a normal countenance, jesting in the intervals with your servants, holding up your end in a sustained discussion, making excuses for your pain and minimizing your suffering.

p. 1019

Living with the Threat of Acute Kidney Stone Events

The pain and agony, along with other effects of kidney stones, are never forgotten. And, the fear they will strike again is ever present, with good reason; they often return time after time. Here are excerpts related to how Montaigne learned to live with and reconcile this threat, while acceding, somehow, that it could be worse.

…in the eighteen months or thereabouts that I have been in this unpleasant state, I have already learned to adapt myself to it. I am already growing reconciled to this colicky life; I find in it food for consolation and hope. So bewitched are men by their wretched existence, that there is no condition so harsh that they will not accept it to keep alive.

p. 697

‘Fear of this disease,’ says my mind, ‘used to terrify you, when it was unknown to you; the cries and despair of those who make it worse by their lack of fortitude engendered in you a horror of it.’

p. 1019

When it assails me mildly it frightens me, for that means for long. But, by nature, it has vigorous and violent spurts; it shakes me to pieces, for a day or two.

p. 1021

I am tested, however, pretty roughly for a beginner, and by a very sudden and very rough change, having fallen all at once from a very gentle and very happy condition of life to the most painful and grievous that can be imagined…The attacks seize me so often that I hardly feel perfect health any more. Yet I have kept my mind, up to now, in such a state that, provided I can hold fast, I find myself in a considerably better condition of life than a thousand others, who have no fever illness but what they give themselves by the fault of their reasoning.

p. 701

But let us come to those examples in which we shall find that it is with pain as with the stones which take on a brighter or duller color according to the foil they are set in, and that it occupies in us only that much room as we give it.

p. 47

Consider how artfully and gently the stone weans you from life and detaches you from the world; not forcing you with tyrannical subjections like so many other afflictions that you see in old people, which keep them continually hobbled and without relief from infirmities and pains, but by warnings and instructions repeated at intervals, intermingled with long pauses for rest, as if to give you a chance to meditate and repeat its lesson at your leisure. They give you a chance to form a sound judgment and make up your mind to it like a brave man, it sets before you the lot that is your condition, the good and also the bad, and a life that on the same day is now very joyous, now unbearable.

p. 1020

Now it has happened again that the slightest movements force the pure blood out of my kidneys. What of it? I do not, just for that, give up moving about as before and pricking after my hounds with youthful and insolent ardor…It is some big stone that is crushing and consuming the substance of my kidneys, and my life that I am letting out little by little, and not without some natural pleasure, as an excrement that is henceforth superfluous and a nuisance. Do I feel something crumbling? Do not expect me to go and amuse myself testing my pulse and my urine so as to take some bothersome precaution; I shall be in plenty of time when I feel the pain, without prolonging it by the pain of fear.

p. 1023

Profiting from Kidney Stones

As it was during Montaigne’s time, and is still now, kidney stones are among just a few conditions ranked as producing the most pain humans can experience. Montaigne writes of suffering greatly from them with some regularity. Yet, he professed having “profited” by the pain and suffering they caused him, mostly through blunting his fear of death, yielding morbidity-free remissions, and realizing he could be much worse off with many other infirmities.

I have at least this profit from the stone, that it will complete what I have still not been able to accomplish in myself and reconcile and familiarize me completely with death: for the more my illness oppresses and bothers me, the less will death be something for me to fear.

p. 698

But is there anything so sweet as that sudden change, when from extreme pain, by the voiding of my stone, I come to recover as if by lightning the beautiful light of health, so free and so full, as happens in our sudden and sharpest attacks of colic? Is there anything in this pain we suffer that can be said to counterbalance the pleasure of such sudden improvement? How much more beautiful health seems to me after the illness, when they are so near and contiguous that I can recognize them in each other’s presence in their proudest array, when they vie with each other, as if to oppose each other squarely!

p. 1021

I argue that the extreme and frequent vomitings that I endure purge me; and, on the other hand, my loss of appetite and the unusual fasts I undergo digest my morbid humors, and nature voids in these stones its superfluous and harmful matter.

p. 1022

Do not tell me that it is a medicine too dearly bought. For what about all the stinking potions, cauteries, incisions, sweatings, setons, diets, and all the methods of cure that often bring us death because we cannot endure their violence and relentlessness? So, when I have an attack, I take it as medicine; when I am exempt, I take it as lasting and complete deliverance.

p. 1022

I notice also this particular convenience, that it is a disease in which we have little to guess about. We are freed from the worry into which other diseases cast us by the uncertainty of their causes and conditions and progress – an infinitely painful worry.

p. 1023

Comments

Montaigne shows how kidney stones were known as one of the most excruciating experiences a human can go through in the 1500s as they are to this day. However, it is near impossible to imagine that anyone in a developed nation during the first half of the 21st century could appreciate kidney stones in the same way as Montaigne. The first-time event sends most all people to the hospital, and most not knowing the cause of the worst pain they’ve had in their life. Subsequent bouts send some back to the hospital and others to their medicine cabinets or searching for other means of relief biomedicine has to offer. No health care system like those in developed nations now existed for Montaigne, but he talks about doctors and apothecaries and the various medical services that were available. He eschewed them having witnessed what becomes of people availing themselves of these services.

In the first place, experience makes me fear it; for as far as my knowledge goes, I see no group of people so soon sick and so late cured as those who are under the jurisdiction of medicine. Their very health is impaired and corrupted by the constraint of their regimens. The doctors are not content with having control over the sickness; they make health itself sick, in order to prevent people from being able at any time to escape their authority.

p. 704

Montaigne wants to break through what he considers biomedical hegemony so that if he must endure kidney stones, he is free to profit from them in ways he values. This made me think of David B. Morris’ formulation of illness and eros in his book of that title, and that Montaigne is exhibiting a form of eros—”medical eros”—in his desire for this profiting while trying to resist “medical logos,” that is, all that biomedicine encompasses. However, in an episode of the podcast, The Clinic & the Person, David Morris took the position that Morris’ “profit” represented more of an acceptance forced on him rather than a desire he sought. I elaborate on Morris’ concepts in a separate blog post.

Also:

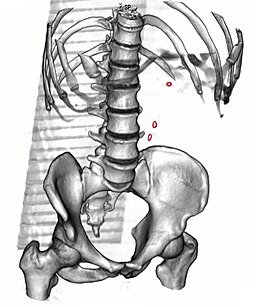

Title image credit: Three Kidney Stones Highlighted in Red. Sanderlewis, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

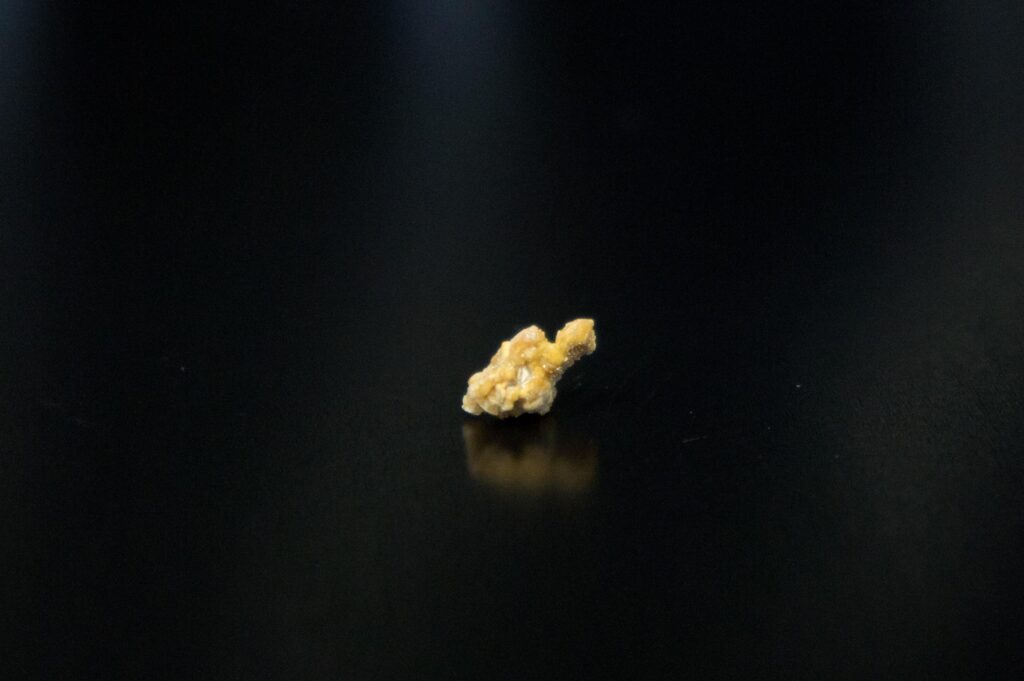

Kidney stone images from Kidneystoners.org.