Human reactions to plagues have been consistent over many centuries, and have led to societal tensions and conflict of all sorts, like: blaming and stigmatizing certain groups for outbreaks; recommending or requiring protective measures; generating and trafficking misinformation; developing and distributing treatments; and conjuring up conspiracy theories and intrigue about everything. Fleeing is also among these human reactions, and analyses of population migrations in response to the Covid-19 pandemic show some common characteristics with a past plague, namely, The Black Death of the fourteenth century. Here, I draw from a literary depiction from The Decameron of population movement during the 1348 visitation of the bubonic plague in Florence, Italy to compare with the population movement out of New York City (NYC) during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic as reported in The Pandemic’s Impact on NYC Migration Patterns.

The Decameron (Florence, Italy, 1348)

As a major commercial hub during the first half of the fourteenth century, Italy operated several ports that became entryways for fleas carrying the bubonic plague bacteria, Yersinia pestis, and transported by infected rats. During the latter part of 1347, merchant vessels brought the plague to the ports of Genoa and Pisa, which then raced through Tuscany, depopulating cities along the way and ultimately to Florence by the end of the year. Just a few months later, the city was laid waste by death, disease, and debauchery (“everyone was free to behave as he pleased”). (p. 8)

Within six months, as Robert Gottfried reports in his book, The Black Death, “as much as a third of the city’s population might have died,” and overall, estimated death rates “ranged from 45% to an incredible 75% of Florence’s total population.” (p. 46) Offering a sense of the city when the plague was at its worst, Gottfried quotes another literary source, Cronaca Fiorentina di Marchionne di Copppo Stefani, in which “the chronicler Stefani claimed that the only sounds that could be heard came from carts—those of the rich, fleeing with their belongings, and those of the charnel crews.” (p. 47)

Giovanni Boccaccio, is one of the three “crowns,” along with Dante and Petrarch, of the early Italian Renaissance in the fourteenth century. Boccaccio eschewed his father’s desire that he become a businessman and opted for the writer’s life. He was in Florence when the Black Plague arrived and took hold. He saw the city quickly descend into ruin, and how dark and bleak life had become for its inhabitants who had not succumbed to the pestilence or the mayhem. What he could offer is what he could write. He wished “to some extent repair the omissions of Fortune…to provide succour and diversion,” but mostly for “the ladies” being “of the more delicate sex.” (p. 3) Boccaccio’s stated hope was that “sorrows are dispersed by the advent of joy,” (p. 4) of the kind he can bring to those who could flee Florence while it was engulfed in pestilence and mayhem.

Thus, The Decameron came about, a book Boccaccio describes as comprising,

one hundred stories or fables or parables or histories or whatever you choose to call them, recited in ten days by a worthy band of seven ladies and three young men, who assemble together during the plague which recently took such heavy toll of life.

p. 3

The stories are also sometimes referred to as novellas.

In the introduction, Boccaccio provides an eyewitness account of life in Florence as the plague ravaged the city. He notes how some, but not all of the inhabitants had the option to flee.

Some people, pursuing what was possibly the safer alternative callously maintained that there was no better or more efficacious remedy against the plague than to run away from it. Swayed by this argument, and sparing no thought for anyone but themselves, large numbers of men and women abandoned their city, their homes, their relatives, their estates and their belongings, and headed for the countryside, either in Florentine territory or, better still, abroad.

p. 9

Boccaccio builds knowledge of these actions into the consciousness of the seven women who would become part of the ten storytellers while they were meeting at the Church of Santa Maria Novella about their predicament (“Novella” in the name of the church having nothing to do with the form of the stories). He then constructs the measures they would take and their reasoning. They begin to talk about their particular situations and options when one of them, Pampinea, makes and argument for their decampment.

What are we doing here? What are we waiting for? What are we dreaming about? Why do we lag so far behind all the rest of the citizens in providing for our safety? Do we rate ourselves lower than all other women?…We have only to recall the names and the condition of the young men and women who have fallen victim to this cruel pestilence, in order to realize clearly the foolishness of such notions.

pp. 15-16, 18

I would think it an excellent idea for us all to get away from this city…We could go and stay together on one of our various country estates shunning at all costs the lewd practices of our fellow citizens and feasting and merrymaking as best we may without in any way overstepping the bounds of what is reasonable…There we shall hear the birds singing, we shall see fresh green hills and plains, fields of corn undulating like the sea, and trees of at least a thousand different species; and we shall have a clearer view of the heavens, which troubled though they are, do not however deny us their eternal beauties, so much more fair to look upon than the desolate walls of our city.

While the ladies were voicing some hesitation about the advisability of executing such a plan without male supervision, three men, all of whom were known or related to one or more of the ladies, approached them. When the men were apprised of the opportunity to join the ladies on their escape, they agreed with alacrity. And, off they went, leaving those behind who had neither the means nor wherewithal to protect themselves in that way, or in any way.

The Pandemic’s Impact on NYC Migration Patterns (New York City, 2021)

As hospitals and morgues in NYC overflowed with people who were dead or close to death from a raging, coronavirus infection, people must have been having conversations along the lines Boccaccio’s seven ladies had in Florence almost 700 years before. And, like the people in Florence then, people with the means to leave NYC followed their lead. The migration from NYC was apparent to people living there, but exactly how many people left, who the people were who left, and where they left for were not known.

The NYC Bureau of Budget undertook an analysis of “out-migration” from NYC during the first few months of the Covid-19 pandemic to answer those and related questions, and published its findings in November, 2021. The analysis was largely based on requests received by the United States Postal Service (USPS) for a change of address form.

Some of the findings that correspond with Boccaccio’s set up for his book based on his observations during the first few months of the plague in Florence as published in the report including the following:

In the first three months of the pandemic, net out-migration from NYC increased by an estimated 130,837 from March 2020 through June 2021, as compared to pre-pandemic trends.

p. 2

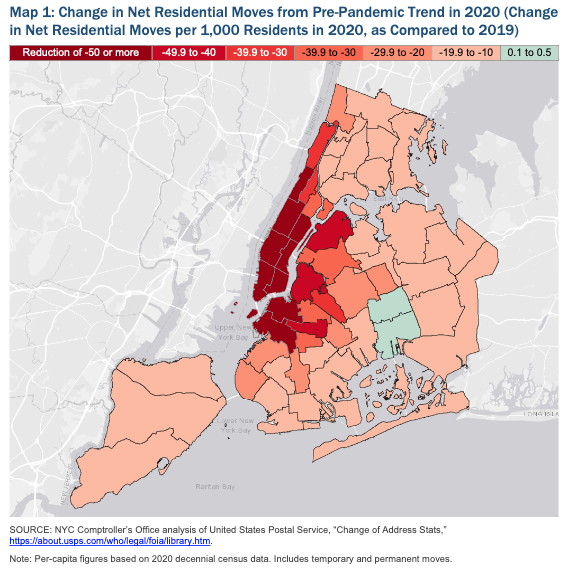

From March to May 2020, more than 60 percent of net moves from city addresses were marked as temporary. (See Map 1 from report.)

Residents in the wealthiest 10 percent of neighborhoods, corresponding to median incomes above $110,000, were 4.6 times more likely to leave than other residents during 2020, recording 109 net move-outs per 1,000 residents vs 24 elsewhere. Such neighborhoods include Park Slope/Carroll Gardens in Brooklyn and Battery Park City/Greenwich Village, Murray Hill/Gramercy, Chelsea/Midtown, the Upper West Side, and the Upper East Side in Manhattan. During the spring of 2020, residents of the wealthiest neighborhoods were 7.2 times more likely to exit.

p.2

Since July 2021, USPS data has shown an estimated net gain of 6,332 permanent movers, indicating a gradual return to New York City, mainly in neighborhoods that experience the greatest flight.

From March through August 2020, net in-migration within New York rose 9 percent in Westchester County but more than doubled on Long Island. More than 59 percent of the gain on Long Island was from temporary moves to Suffolk County, home of the Hamptons.

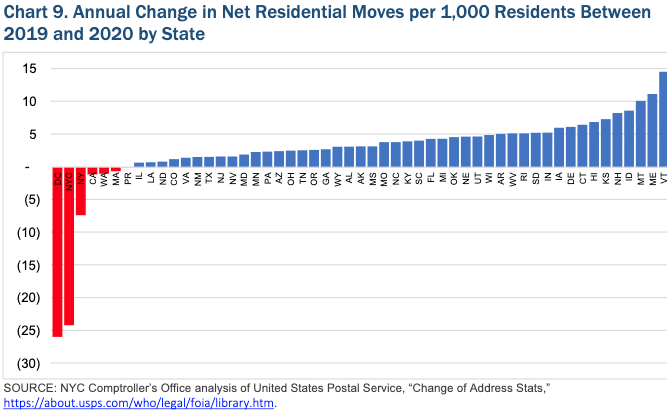

Migration out of NYC went beyond New York borders as well, with most of it going to other states in the Northeast or decidedly less dense areas such as in mountain and plains states (see Chart 9 from report.)

p. 13

Conclusion:

Disease, illness, death, and grief are major aspects of the human condition, and as such, a concern of the humanities. Plagues draw particular attention from the humanities because of the profound effects plagues have on individual human lives in the way of their wellbeing, capacity, and potential, and on their support structures such as governance, commerce, and protection. In many cases, renderings of particular disease and illness scenarios add to classic biomedical and public health texts and teachings.

The Decameron is a case in point as it concerns human reactions to infectious plagues, and in particular population migrations. As a backdrop to the stories comprising the book, Boccaccio used the visitation of the Black Plague in Florence during 1348. His set up for the book reflects the time when, though nothing was known about germ theory or the cause of plague specifically, people knew it was deadly and contagious. A primary response among those who could was to vacate the city, at least temporarily. Almost 700 years later, an apparent plague descends on NYC, and although people there had a good idea an infectious agent was at work, they also saw that it was deadly and contagious. Many of those who could—the monied and connected classes—also chose to vacate the city, at least temporarily. Thus, from The Decameron, and other works, we could have expected that when the Covid-19 pandemic emerged, people who could, headed for the hills.

Works Cited:

The Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio, [GH Mc William, translator], New York, Penguin Classics, 1972 (written in 1351-1353).

The Black Death, Robert F. Gottfried, New York, The Free Press, 1983.

The Pandemic’s Impact on NYC Migration Patterns, New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Bureau of Budget, November 2021.

Also:

This topic is taken up further in an episode of the podcast The Clinic & The Person, as well as are other examples of literary sources showing how human reactions to plague over the centuries manifested during the Covid-19 pandemic.

A literary explication of how the plague spreads that offers an elaboration on biomedical texts is available in Maggie O’Farrell’s novel, Hamnet, which is covered here in this blog.

Cover image credit: The Plague of Florence, 1348; Etching by Sabatelli the elder (1772-1850). Source: Wellcome Collection

Edited by Lucy Bruell