Øystein Ustvedt

Alison McCullough – translator

New York

Thames & Hudson

2020

223 pages

According to the Art:

National Museum (Oslo) art curator and Munch expert, Øystein Ustvedt, brings together art history and Edvard Munch’s biography in explaining how his work depicts both emotional and subjective aspects of the human condition, to include illness and its consequences.

Synopsis:

Most people hearing the name Edvard Munch (1863-1944) will likely associate him with his painting, The Scream. Not as many will know that over a period of sixty years he produced over 1,800 paintings, scores of which have made Munch one of the most important painters during the last 150 years. He was also, to varying degrees, an author, poet, graphic artist, sculptor, draughtsman, photographer, and filmmaker. As might be expected, there is no shortage of books about the famed, Norwegian artist. Nevertheless, the National Museum (Oslo) art curator and Munch expert, Øystein Ustvedt, saw a need for “an up-to-date and reliable publication, written for a more general readership.” (p. 9) The book proceeds chronologically, with individual chapters covering the 1880s; 1890-1900; 1900-1916; and 1916-1944. Each chapter comprises several sections of just a few pages each, rarely more than ten. Colored illustrations accompany most of them, with 130 in all.

Ustvedt notes that Munch is considered “an autobiographical artist,” meaning his “work is formulated in a way that is connected to subjective engagement and emotional involvement.” (p. 32-33) Munch’s biography is filled with anxiety, illness, death, and grief among himself, family members, and friends, and is amply represented in his oeuvre. He is known to have said, according to another Munch biographer, Sue Prideaux, “Illness, insanity and death were the black angels that hovered over my cradle.” (Prideaux, p. 17) Ustvedt, however, also captures interests beyond these elements of his biography.

His works thematize the love, suffering and pain of the human condition, as well as the lyrical beauty of nature and the more mundane aspects of everyday life…His works bear witness to his multifaceted and dramatically inclined nature; to an artist who was simultaneously a tradition-bound realist and an experimental modernist.

p. 10

Changing styles and preferences in art during Munch’s active years affected him and his work. Ustvedt describes how his style wasn’t always in synch with aesthetic characteristics critics, curators, and collectors valued in paintings at a given time, and how his fortunes varied accordingly. For example, he tells how the first version of Munch’s painting, The Sick Child, a rendering of his older sister succumbing to tuberculosis, created when realism remained the preferred style, was considered “unaccomplished and unfinished, and was described by many as a miscarriage—a failure.” (p. 14) Munch was savaged and openly ridiculed. In order to gain favor towards winning a grant to study in Paris, he produced another version of the painting closer to realism (Spring), which accomplished his objective. When the artistic form known as “expressionism” was better appreciated, The Sick Child was eventually regarded as the “first step in [Munch’s] journey to become one of the great, groundbreaking artists of his time.” (p. 29)

Munch returned to certain paintings often for various reasons, such as evolving his techniques and interpretations. Ustvedt refers, again, to The Sick Child as a case in point.

The Sick Child was the motif Munch returned to most often, and over the longest period of time. He created six paintings over forty years – the format, composition and perspective were always the same, but the execution varied. The paintings are the same, and yet different. Viewed together, they reveal Munch’s development as an artist: from painterly realism to intense expressionism, and from explosive colours to decorative surface painting.

p. 173

The history of individual works painted several times over a prolonged period can reveal how what they convey or the attention they attract can change. Ustvedt notes how, in particular, the paintings often evolve “from the depiction of experienced reality and emotional content, to a greater emphasis on the formal execution,” that is, more about “precisely how, rather than what.” (p. 173)

At various times, Munch applied different methods and processes. As an example, Ustvedt uses the painting, Death in the Sickroom, which he refers to as “Munch’s most monumental depiction of loss within a family.” (p. 91)

The execution of the painting itself conveys smell, moisture and bodily fluids involved in death and illness. The pale colours strengthen the theme’s impact, as do details such as the shapeless duvet, the blood-red medicine bottle, and the chamber pot sticking out from under the sickbed.

p. 92

Usvedt shows in a succinct yet thorough fashion, that through genre, figurative, portrait, and landscape motifs, and an expansive range of subjects and interests, Munch’s work covers a wide swath of the human condition. Of his more important and recognized works are those providing perspectives on the effects anxiety, illness, death, and grief cause people.

Analysis

Ustvedt’s survey of Munch’s work is comprehensive, but because of Munch’s particular interest in health problems and their consequences, much of what he covers concerns how Munch addresses anxiety, illness, death, and grief. And, he intertwines how changes in artistic trends and interests affected his work on these subjects. For example,

With his personal approach, Munch added an emotional dimension to the portrayal of loss. The execution of The Sick Child explicitly connected the painting’s form with one for the most difficult of life’s experiences: that of losing a child.

p. 34

And Ustvedt tells of how this relationship between Munch’s wrenching emotional connection to the evolving form of the painting continued for forty years. He’s known to have said that “few artists ever experienced the full grief of their subject as I did in The Sick Child,” while at the same time, as Ustvedt reports separately, Munch credits the progress he made in his art to the it: “Most of what I have done since was born in this painting.” (p. 31)

Munch’s family biography of illness and death would scar anyone, and it did scar him, but to his and eventually our benefit. Ustvedt saw how “personal suffering and self-imposed renunciation became a theme with many variations in Munch’s oeuvre and the very cornerstone of Munch’s perception of himself as an artist.” (p. 92) Prideaux reported that Munch, himself, considered his “maladies” essential to his art and so he courted and welcomed them.

I must retain my physical weaknesses; they are an integral part of me. I don’t want to get rid of illness, however unsympathetically I may depict it in my art…My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder. My art is grounded in reflections over being different to others. My suffering are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings.

p. 251

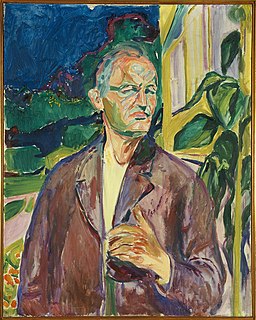

Munch brings credibility to his renderings of illness and its most dire consequences. But, with such an encompassing body of work on this subject, which of Munch’s painting are best seen to capture both his painterly style and emotional expression? In the book, Ustvedt identifies a few in particular, including: The Sick Child; Spring; The Smell of Death; Death in the Sickroom; Melancholy; Blossom of Pain; Self-Portrait of the Spanish Flu; Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed; and The Scream. When I posed this question to Ustvedt during an interview with him at the National Museum in Oct, 2023, he presented a similar list and explained the basis for his choices. The interview is published in an episode of The Clinic & The Person podcast. These paintings can be viewed through the online collections of the National Museum in Oslo with the exception of The Smell of Death and Self Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed, which can be viewed through the online collections of the Munch Museum in Oslo.

Ustvedt ties together art history and Munch’s biography in explaining how his work depicts both emotional and subjective aspects of the human condition, to include illness and its consequences. Ustvedt also suggests we approach Munch’s work with all our senses activated and be prepared to develop synesthesia, as least for a while.

Also:

See earlier blog piece focusing on Munch’s paintings and the soul, and where several of the paintings described above are produced.

An earlier blog piece considered Munch’s The Sick Child.

I reference Sue Prideaux’s biography of Munch, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream, in a couple of places in the piece.

Edited by Lucy Bruell.