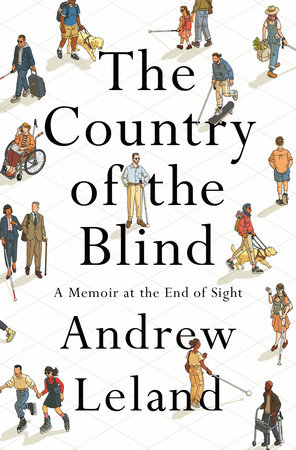

Andrew Leland

New York

Penguin Press

2023

339 pages

According to the Art:

The book is classified as a memoir, and while it has the elements of a memoir, Leland crosses seamlessly into other genres, such as history, philosophy, political science, and long-form journalism. He plunges into the country of the blind, which for him is a “teeming variety of their stories of struggle, adaptation, and adventure.”

Synopsis:

Andrew Leland has been losing his vision since high school, slowly, but definitively. The cause is retinitis pigmentosa (RP), a group of eye diseases affecting light-sensitive cells in the retina, the rods and cones particularly. People with RP often first notice problems with seeing at night, later their peripheral vision narrows progressing to blurred images making reading impossible and moving unaided hazardous. RP often manifests in childhood or adolescence and progresses at varying rates—including into old age—before legal or total blindness is reached. Leland wrote this book while early into his fifth decade, more than twenty years since his RP diagnosis, and after he qualified as legally blind.

The book is classified as a memoir, and while it has the elements of a memoir, Leland crosses seamlessly into other genres, such as history, philosophy, political science, and long-form journalism. As much as he had a professional interest in telling his story as a writer, editor, and podcaster, he was motivated as a person in the midst of losing vision and wondering what might be ahead of him.

The blinder I get, the more curiosity I feel about the world of blindness and what possibilities might exist there. So I went out into the world, to find a more accurate image of what might be waiting for me.

p. xv

As a consequence of his investigations, Leland sees that the “book isn’t merely the account of my own experience of vision loss…it’s the chronicle of an intentional journey I took into the greater world of blindness.” (p. xvi-xvii)

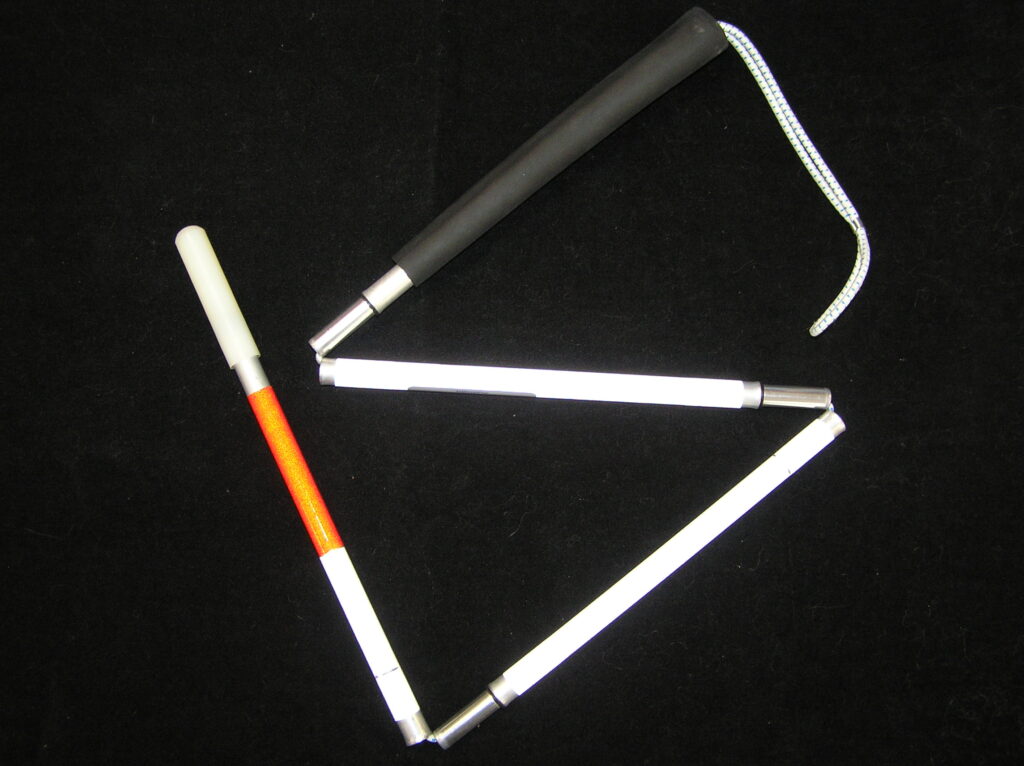

Across three sections, bookended by an introduction and a conclusion, Leland plunges into the country of the blind, which for him is a “teeming variety of their stories of struggle, adaptation, and adventure.” (p. xxv) He visits his eye doctors; advocacy organizations for the blind; disability advocates; and blind writers, artists, educators, entrepreneurs, and technology developers. He attends conferences and enrolls in training programs. He tries out various assist technologies, and learns how to use screen readers, braille, and collapsible canes. He researches the history and politics of government and nongovernment support for the blind, and the history and politics of research initiatives. He wonders about how life with his wife and son might change. He draws from literature, poetry, art, and philosophy to find his place in a world he is losing earthly sight of. It’s liminal, it’s ambiguous, it’s uncertain…it’s ok.

Analysis:

Leland’s title, The Country of the Blind, is taken from an the H.G. Wells short story of the same name, and from the proverb, “In the Country of the Blind, the One-Eyed Man is King.” In most interpretations, it serves as a warning to those who come into an environment in which they believe their superior traits will afford them a dominate place, only to find it is they who are at a disadvantage. Leland’s use of the story seems directed at establishing a platonic ideal for blindness. All the inhabitants in Wells’ country are blind and have been for fifteen generations. When a sighted man, Nunez, finds himself in the country of the blind, he encounters a civilization that has evolved past the need for sight or even the conception of sight; if this population has disabilities, they are not related to sightlessness. Nunez’s sight, in fact, brings him disadvantages and disabilities, not his expected reign as king.

Leland wants to approach this platonic ideal, but not fully attain it. His hope is that blindness becomes “merely a characteristic,” as it is in Wells’ County, but that saying blindness is not a disability goes too far. In his formulation, he would be “perfectly capable and independent” with “alternative techniques” various assist technologies offer, (p. 236) though not to the extent where Ray Kurzweil’s prediction of how,

the unimpeded development of technologies—machine vision, synthetic speech, artificial intelligence—would eventually lead to a future where ‘disabilities such as blindness, deafness, and paraplegia are not noticeable and are not regarded as significant.’ [For Leland,] Kurzweil’s enthusiasm for this trans-humanist future, where bodily difference gets absorbed into a kind of cyborgian democracy, erases much of what is interesting, powerful, and beautiful about disability.

p. 191

Towards that end, Leland describes how he has “been searching for blind mentors, people who in their inhabiting of blindness make it seem not just like something that can be overcome, but like something that’s intellectually productive, interesting, even cool.” Leland found, however, counterintuitively to his way of thinking,

the medical world is by definition positioned against blindness—in a way that makes it hard to conceive that some blind people (particularly those blind from a young age) might want to remain blind, or that being blind has any value in and of itself.

p. 212

He will have to fight his way to achieve the balance he seeks. And he seems up for the challenge when he says his “inclination is to just put my head down and barrel into blindness becoming proficient in all of the skills it requires and then moving on with my life.” (p. xxii)

As a man of letters, and as a writer, Leland tells of seeking mentors from among important writers and artists who were also challenged with varying degrees of blindness. Among them is Jorge Luis Borges, who apparently influenced Leland’s ideal about blindness, writing “It should not be seen in a pathetic way. It should be seen as a way of life: one of the styles of living.” (p. 162) From other blind writers, and from James Joyce especially, he learns that their writing became more “aural (and oral)”, and he quotes Samuel Becket’s remarks about a particular James Joyce novel that “it is to be looked at and listened to.” (p. 134) Joyce also contributed to Leland’s ideal, “What the eyes bring is nothing. I have a hundred worlds to create, I am losing only one of them.” (p. 288) Leland might get his steeliness from John Milton who he quotes responding to a charge that his blindness could function as a metaphor for “gaps in his reasoning,”

I would, sir, prefer my blindness to yours; yours is a cloud spread over the mind, which darkens both the light of reason and conscience; mine keeps from my view only the coloured surfaces of things, while it leaves me at liberty to contemplate the beauty and stability of virtue and of truth.

p. 48

Others he turns to are no less than Cicero, Sophocles, Homer, and Shakespeare.

Leland’s liminal, ambiguous, and uncertain state is a source of frustration, but one he strives to accommodate: “Living in this weird shadowy landscape between blindness and sight has forced me to reckon with this, and to try to let go of my desperate desire for resolution.” (p. xxii). He finds Beckett’s play, Endgame, helpful in its acknowledgement of this predicament.

Beckett’s play sits with the pain and ambiguity of the in-between, a world in which the sun has set but it’s not night, where the sky is not simply gray but ‘light black.’ This is precisely my experience of blindness: a long decline in vision that will almost certainly end with the disappearance of form and detail, but with a paradoxical sense that even as the decline continues, it might never quite arrive at its terminus. I’m living in this infinite endgame, a frozen twilight where I’ve gone blind but still can see.

p. 283

Leland does not spare the health care system any critiques, but none that is not commonly heard. He expresses frustration around the inconsistencies in what he is told about the rate of deterioration in his eyesight he can expect. He notes that much rides on the accuracy of this rate. He also notes the frequency with which his physicians’ reference “the incredible work occurring in clinical trials,” giving him the sense that “the field seems to be in a permanent state of promising development,” but that he is “resigned to the fact that if this promise is ever realized, it will be long after it’s of any use to me.” (p. 201) A cruel hoax.

Nevertheless, Leland is a happy warrior. As far as he’s concerned, “reading braille is marvelous, and blindness opens up interesting hermeneutic and epistemological questions that I could spend the rest of my life exploring. A full and joyous blind life is indeed possible.” (p. 215) He will go about his country without fear of a one-eyed king.

Also:

Leland offers a literary description of RP to compare with a biomedical description. His description:

I have severe tunnel vision, but what I see doesn’t look like a tunnel; the walls or the enclosure aren’t visible. I have the strongest sense of the contours of my blindness in periods when my vision changes—when suddenly there are things I don’t see that I ought to, that I saw until recently.

p. xiv

A biomedical description from Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 21st Edition:

Retinitis pigmentosa is a general term for a disparate group of rod-cone dystrophies characterized by progressive night blindness, visual field constriction with a ring scotoma, loss of acuity, and an abnormal electroretinogram (ERG). It occurs sporadically or in an autosomal recessive, dominant, or X-linked pattern. Irregular black deposits of clumped pigment in the peripheral retina, called bone spicules because of their vague resemblance to the spicules of cancellous bone, give the disease its name.

The 2017 French movie, Ava, features the acute, behavioral reactions of a thirteen-year-old girl coming to grips with losing vision from RP.

Edited by Lucy Bruell.