Kazuo Ishiguro

New York

Vintage International

2005

288 pages

According to the Art:

The novel can be read as simply a dystopian story. But it can also be read as an ethical analysis of human cloning technology applied to organ supply, whether the author, Kazuo Ishiguro, had that purpose in mind or not.

Synopsis:

The story follows the intertwining fates of Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy from the time they first came together as young students at Hailsham, ostensibly a boarding school in England, until their fates were no longer intertwined. The three of them progressed through Hailsham together as children. At age sixteen, finished at Hailsham, they were relocated to new living arrangements where they watched over each other before sent to their destinies.

Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy, as all who were placed at Hailsham, were not students, they were human clones created and nurtured for the purpose of supplying human organs; Hailsham was not a school, but rather a human organ farm, where “guardians” protected their bodies and formed their minds. Kathy tells the story of Hailsham looking back after having passed through it many years before, and through her relationships with Ruth and Tommy.

The three of them had a seemingly normal boarding school experience, but the students nevertheless felt unsettled early on during their time at Hailsham, as Kathy recalls.

Even at that age—we were nine or ten—we knew just enough to make us wary of that whole territory. It’s hard now to remember just how much we knew by then. We certainly knew—though not in any deep sense—that we were different from our guardians, and also from the normal people outside; we perhaps even knew that a long way down the line there were donations waiting for us.

p. 69

They would learn when they got older that their nagging suspicions were justified. Along the way to those realizations, the students learned their lessons, played their games, spread their gossip, pursued their romances, satisfied their urges, dreamed of their futures, and, for as long as they could, ignored their destinies. The destinies the Hailsham students ignored eventually foreclosed on their dreams. A rogue Hailsham guardian, stepping beyond limits set for how much students can be told about their future, confirmed what they had been expecting.

None of you will go to America, none of you will be film actors. And none of you will be working in supermarkets as I heard some of you planning the other day. Your lives are set out for you. You’ll become adults, then before you’re old, before you’re even middle-aged, you’ll start to donate your vital organs. That’s what each of you was created to do.

p. 81

But still, their lives were close enough to ordinary humans that they could consider similar trajectories for themselves. Such thinking made some of them vulnerable to rumors about deferments of three or four years before their services in organ donation commenced. Some were also convinced their lives would conform to those of their “possibles,” who were the humans they were cloned from, and so they searched for them. Though they were all told that as clones they would never produce babies, Kathy, inspired by a song she often listened to—Never Let Me Go—dreamed she would someday. All were mirages. They all went on to become donors until they “completed.”

Before that eventuality, however, Kathy and Tommy sought out the former guardian who they thought was a keeper of the secrets surrounding Hailsham. The guardian told them how Hailsham was created to treat human clone organ donators better than the traditionally secretive and impoverished lives they led before released into the donor pool.

For a long time you were kept in the shadows, and people did their best not to think about you. And if they did, they tried to convince themselves you weren’t really like us. That you were less than human, so it didn’t matter. And that was how things stood until our little movement came along.

p. 263

The “little movement” achieved a measure of support and visibility while producing several cohorts of organ donors who “grew up in wonderful surroundings…[and] were kept away from the worst of the horrors.” (p. 261) Eventually, a scandal involving human cloning technology unrelated to the movement nevertheless made continued public support for it untenable and led to its demise—Hailsham had itself completed. But because human clones were still needed for organs, they were relegated out of sight so they could be out of mind.

Analysis:

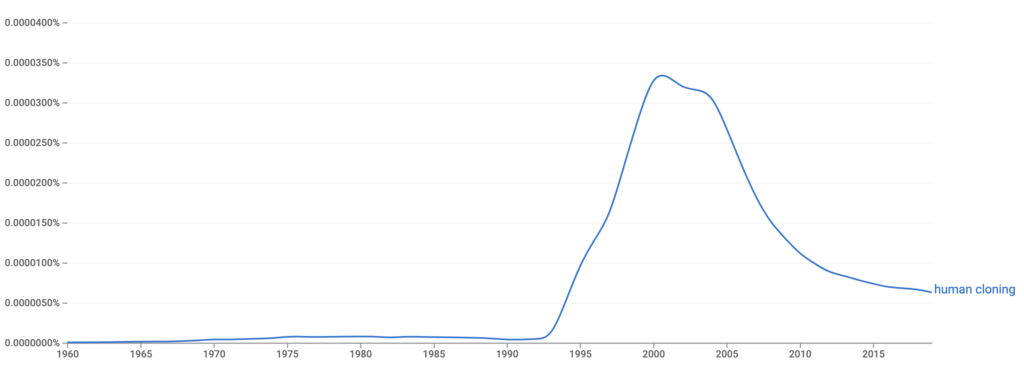

The novel can be read as simply a dystopian story. But it can also be read as an ethical analysis of human cloning technology applied to organ supply. Public interest in human cloning technology was peaking during the time this novel was published in 2005 (see Ngram showing the frequency the term “human cloning” appears “in a corpus of books [e.g., ‘British English,’ ‘English Fiction,’ ‘French’] over the selected years”).

The novel brings to light ethical implications the technology generates, in particular whether there is a way human clones used for organ donations can be treated that ever makes the practice acceptable. The ethics involves an arrangement—give the human clones a good life until the time comes to give up their organs. The acceptability of the arrangement depends on whether providing the clones an existence “as sensitive and intelligent as any ordinary human being,” rather than an existence “only to supply medical science” meets ethical standards. (p. 261)

Ishiguro is seductive. His prose can lead us along thinking that this is a fair tradeoff. A guardian defended the tradeoff to Kathy and Tommy this way:

Whatever else, we at least saw to it that all of you in our care, you grew up in wonderful surroundings. And we saw to it too, after you left us, you were kept away from the worst of the horrors…I hope you can appreciate how much we were able to secure for you. Look at you both now! You’ve had good lives, you’re educated and cultured.

p. 261

Hailsham clones, however, are offered only the opportunity to be as sensitive and intelligent as humans, not to be humans and not to be with humans. But as we watch clones we have come to know complete, we are startled, come to our senses, and say, “wait, is that ok?” We ask ourselves, is it enough to walk like humans, talk like humans, feel like humans, harbor aspirations like humans, have sex like humans, and suffer like humans—while never integrating their lives with humans—to gain the moral standing of humans?

If so, then whether it’s okay to treat clones well before their organs are confiscated depends on which of two moral principles prevail: one asserting that humans cannot under any circumstances serve as a means to an end (i.e., deontological), or one asserting that the greater good for the greater number can justify humans serving as a means to an end (i.e., utilitarian). In current times, moral principles against the use of humans as a means to an end would be favored, especially when the means require human sacrifice, and so readers equating human clones to humans would say it’s not okay. If this is how we read the story, then it should end with the preclusion of human clone use for human organ supply altogether. The story does not end there, though.

The story ends, instead, with the collapse of the movement, and the return of the clones to the shadowy existence they led before. And there the story leaves us, and the clones, and their organs, and with an impression that humans pressed with a desperate need will avert their gaze from unpleasant realities and tricky ethical dilemmas. That makes for an incomplete—nay, nihilistic—ethical analysis. However, Ishiguro has said that his story is about human relationships within a compressed time period short life spans create. He used the life span of the human clones as the device for that purpose. In interviews, Ishiguro has further said that he recognizes the impulses some readers will have to consider the ethical dimensions the story offers, and he does not object, but that was not his intention.

Nevertheless, the story also highlights how novels can serve as a medium where particular ideas concerning highly charged and contentious subjects can be fully explored without explosive reactions derailing rational arguments and productive debates. And as as the speculative element of the novel suggests, consideration can be given to the perspectives of human clones in debates concerning their fates.

Also:

In another angle to the ethics raised in Never Let Me Go, Jody Picoult, in her novel, My Sister’s Keeper, considers parents of a child needing a bone marrow transplant conceiving another child to serve as the source for the transplant.

Never Let Me Go was made into a movie and released in 2010.

Kazuo Ishiguro won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Literature.