And then—the watcher at his pulse took fright. No one believed. They listened at his heart. Little—less—nothing!—and that ended it. No more to build on there. And they, since they Were not the one dead, turned to their affairs.

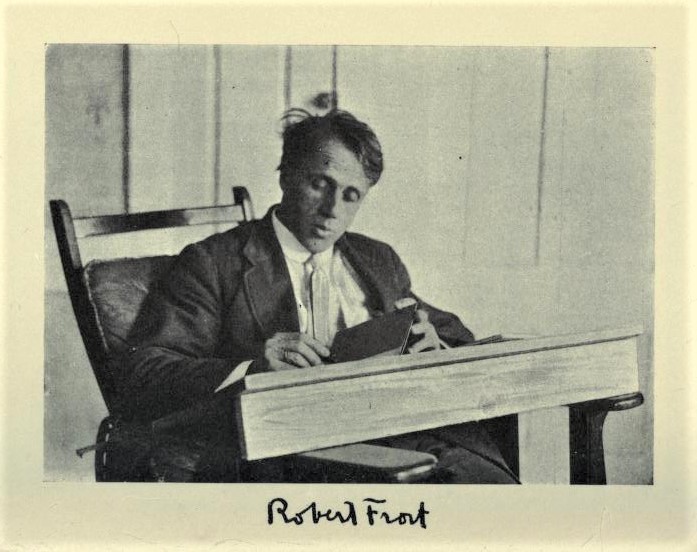

And so ends the Robert Frost poem, “OUT, OUT—“. The connection of the title to Macbeth’s brief soliloquy upon hearing of Lady Macbeth’s death suggests that Frost was referring to resignation and futility with regard to injury and death, and in this case concerning the death of a boy whose hand was sawed off accidentally. This reaction is in keeping with life in early twentieth-century agrarian societies wherein the important task was to keep living. Western societies in the twenty-first century, in contrast, are structured to provide health care for purposes beyond just those necessary to keep living. Health care is now seen as being important for individuals who seek equal opportunities to pursue their own life plans, and often as a basic good of a caring and compassionate society. The end of the Frost poem read in the twenty-first century can thus appear more like banality than the futility Frost meant to convey.

Hannah Arendt used the concept of banality when trying to explain the evil of Adolf Eichmann’s behavior as a Nazi leader involved in the mass murder of millions of Jews. Eichmann claimed he was only obeying orders and that the guilty party was the state. He was just going about his job.1 Evil can be banal when the evildoers “have never given thought to the matter.”2 In “OUT, OUT—“, no thought is apparently given once there is “no more to build on there.”

Other writers have described this banality. Jarrell3 in his poem referred to

Our little flock Of blue-smocked sufferers, in naked equality, Longs for each nurse and doctor who goes by Well and dressed, to make friends with, single out the I That used to be, but we are indistinguishable.

During treatment for his prostate cancer, Broyard observed that “To most physicians, my illness is a routine incident in their rounds, while for me it’s the crisis of my life.”4 Both these writers have encountered a banality that exists in health care. They are the object of someone else’s routine job and not the object of their compassion and care.

The Arendt concept of banality involves the failure to remember or think about what a person is doing and how it affects others. The concept may have applicability in understanding and improving relationships between health care professionals and patients. But, before such a conclusion can be made, a formal analysis of the viability of banality as a useful concept will be necessary. While the field of psychology should be part of this analysis, so should the field of literature.

References:

- Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. New York: Penguin, 1964.

- Arendt, Hannah. Responsibility and Judgment. New York: Schocken Books, 2003.

- Jarrell, Randall. “The X-Ray Waiting Room in the Hospital.” On Doctoring: Stories, Poes, Essays. Eds. Richard Reynolds and John Stone. 3rd ed. New York: Simon & Shuster, 2001: 154.

- Broyard, Anatole. “Doctor, Talk to Me.” On Doctoring: Stories, Poems, Essays. Eds. Richard Reynolds and John Stone. 3rd ed. New York: Simon & Shuster, 2001. 166-72.

*Photographic portrait of American writer Robert Frost (1874-1963) sitting at a desk. From Tendencies in Modern American Poetry by Amy Lowell. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1917, p. 77. Includes replicated signature. Photographer unidentified, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons