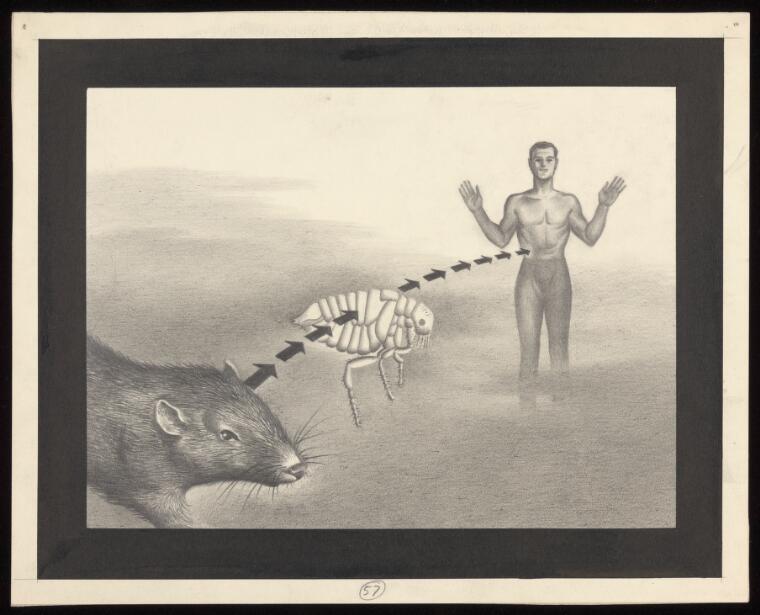

Though it terrorized and depopulated civilizations episodically for thousands of years, only in the last century did scientists discover how the plague wreaks such havoc. The plague spreads its killing agent, the bacteria Yersinia pestis, among humans mostly through the right animals and the right insects, under the right conditions and at the right times. Biomedical texts describing the spread of plague obscure many key events behind technical words and phrases. People new to biomedicine or people not in biomedicine can be left wondering how the plague actually spreads among humans.

In her recent novel, Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell, describes how two characters in the book—eleven-year-old twins, Hamnet and Judith, who live in Stratford, Warwickshire, England—contract the plague in 1596. Her text aligns with modern-day biomedical explanations, but she expands on them by placing the many necessary steps of infection spread among story details, thereby showing how everyday activities can spread the plague, albeit as they were four hundred years ago.

To illustrate this point, I juxtapose a compressed biomedical explanation of how the plague spreads from a recent review published in a prominent medical journal with excerpts from O’Farrell’s novel where she describes how the plague reached and infected her two young characters.

The Biomedical

From: Glatter JA, Finkelman P. History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19. American Journal of Medicine 2021; 134(2): 176–181.

An ancient disease, its bacterial agent (Yersinia pestis) is an aerobic, gram-negative coccobacillus in the family Enterobacteriaceae. Its primary vector for transmission is the Xenopsylla cheopis flea, although roughly 80 species of fleas can carry it. During the Black Death, the flea was transported by the black rat or Rattus. A controversial new theory argues that ectoparasites such as human fleas and lice also spread the disease during the second plague pandemic. Fleas can also survive in infected clothing or grain. The bacteria multiply in infected rodents (more than 280 mammalian species can serve as carriers) and block the fleas’ alimentary canal, causing the fleas to regurgitate the Y. pestis bacteria into its animal host…Plague transmission is generally from infected fleas by rodent vectors or, rarely, in clothing or grain but may also occur through ingesting contaminated animals, physical contact with infected victims, or direct inhalation of infectious respiratory droplets.

pp. 177-178

The Literary

From: Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell, New York; Alfred A. Knopf, 2020.

Here are excerpts from the novel where story details include necessary and complex sequences of events for plague to spread.

Timing is everything…

For the pestilence to reach Warwickshire, England, in the summer of 1596, two events need to occur in the lives of two separate people, and then these people need to meet. The first is a glassmaker on the island of Murano in the principality of Venice; the second is a cabin boy on a merchant ship sailing for Alexandria on an unseasonably warm morning with an easterly wind.

p. 140

The glassmaker gets hurt and loses two fingers in his factory in Murano. A fellow worker fills in for him and packs up an order of glass beads for shipment to England…

One of his fellows, then, is the one to pack up the tiny red, yellow, blue, green and purple beads into boxes the following day. This man doesn’t know that the master glassmaker—now at home, bandaged and dosed into a stupor with poppy syrup—usually pads and packs the beads with wood shavings and sand to prevent breakage. He grabs instead a handful of rags from the glassworks floor and tucks them in and around the beads, which look like hundreds of tiny, alert, accusing eyes staring up at him.

pp. 140-141

At the same time, the cabin boy is sent onshore in Alexandria to fetch provisions for the crew, where he encounters a man with a monkey…

The monkey climbs up the boy’s arm, using all four of its feet, across his shoulders and up on to his head, where it sits, paws buried in the boy’s hair…What the boy doesn’t know—can’t know—was that the monkey leaves part of itself behind. In the scuffle, it has shed three of its fleas…One of these fleas falls, unseen, to the ground, where the boy will unwittingly crush it with the sole of his foot. The second stays for a while in the sandy hair of the boy, making its way to the front of his crown. When he is paying for a flagon of the local brew in the tavern, it will make a leap—an agile, arching spring—from his forehead to the shoulder of the innkeeper.

pp. 142-144

The cabin boy returns to the ship with the flea, and the ship sets sail…

The third of the monkey’s fleas will remain where it fell, in the fold of the red cloth tied around the boy’s neck, given to him by his sweetheart at home…The boy will pick up his favourite of the ship’s cats,…and nuzzle it against his neck. The flea, alert to the presence of a new host, will transfer itself from the boy’s neckerchief, to the thick, mild-white fur of the cat’s neck. This cat, feeling unwell… will take up residence, the next day, in the hammock of the midshipman. When he, that night, comes to his hammock, he will curse at the now-dead animal he finds there.

pp. 144-145

Four or five fleas, one of which once belonged to the monkey, will remain where the cat lay. The monkey’s flea is a clever one, intent on its survival and success in the world. It makes its way, by springing and leaping, to the fecund and damp armpit of the sleeping, snoring midshipman, there to gorge itself on rich, alcohol-laced sailor blood…Three days out, the midshipman is unwell…Shortly afterwards, they dock at Aleppo…

‘Ah, says the captain, how is the man…the, well, midshipman?’ The physician scratches under his wig…’Dead, sir.’

A.L. Tarter.

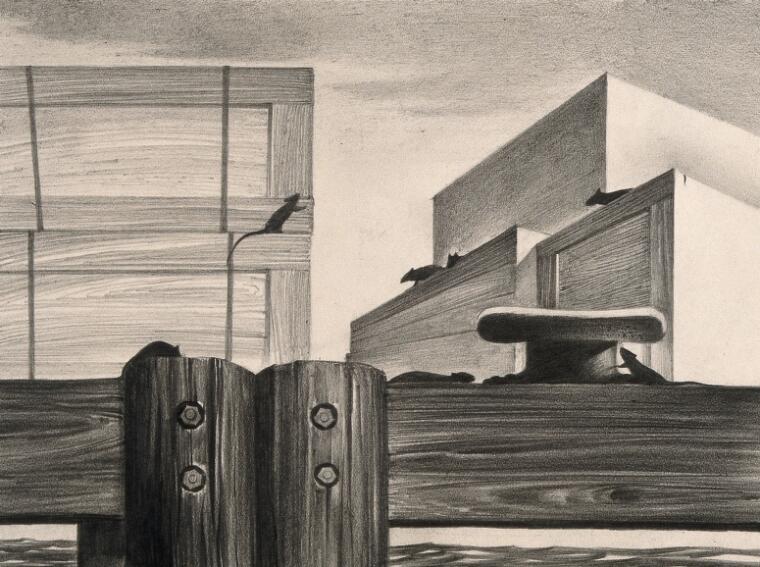

Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

The ship arrives in Murano where the cargo taken on includes the glass beads heading for England. The cabin boy meets the glassmaker while looking for cats that can cull the ship’s rat population…

He is gesturing to the sailors, to his boxes, while gripping his cart, and the boy sees that the first two fingers of his and are missing…He is calling to the sailors, gesturing at the ship with his good hand, at his boxes, and the boy can see that the cart is about to lurch sideways, that the boxes will soon be spilt all over the dockside. He leaps forward, rights the cart, grins at the surprised face of the man with the mangled hand, then darts away because he has seen, underneath a stall selling fish, the whiskered, triangular faces of several cats.

pp. 147-148

Unbeknown to them both, the flea that came from the Alexandrian monkey—which has, for the last week or so, been living on a rat, and before that the cook, who died near Aleppo—leaps from the boy to the sleeve of the master glassmaker, whereupon it makes its way up to his left ear, and it bites him there, behind the lobe. He doesn’t feel it in the cool air of the misty canal has rendered his extremities sensationless, and he is intent only on getting the beads aboard the ship.

While at sea heading to England, fleas find shelter in the boxes with glass beads…

The Venetian cats, when not killing rats…sleep in the hold, on the boxes of beads from Murano…When the cats die—and they do, in succession, one by one—their bodies remain unfound, on top of these boxes. The fleas that leapt from the dying rats into their striped fur crawl down into these boxes and take up residence in the rags padding the hundreds of tiny, multi-coloured millefiori beads (the same rags put there by the fellow worker of the master glassmaker; the same glassmaker who is now in Murano, where the glassworks is at a standstill, because so many of the workers are falling ill with a mysterious and virulent fever).

pp. 148-149

A.L. Tarter

Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

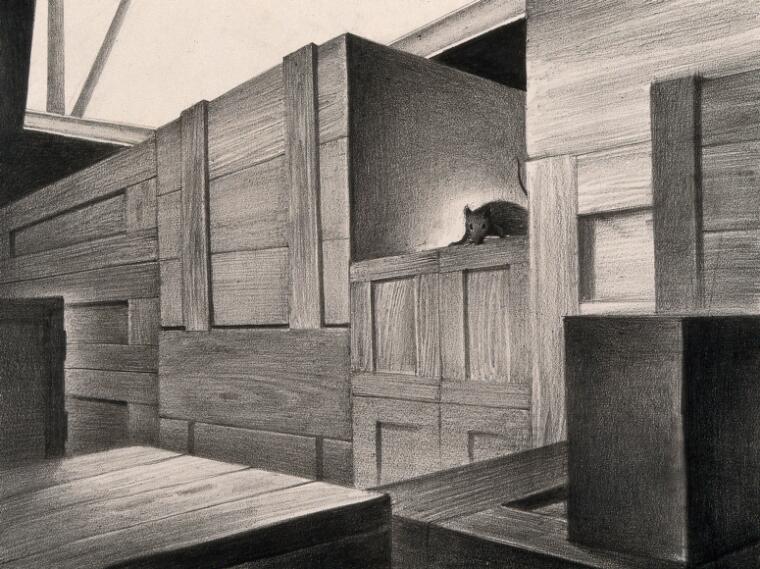

The ship arrives in London and the glass beads are taken to a warehouse before they are picked up for transport to its destination…

The boxes of glass beads, crafted by the glassmaker on the island of Murano, just before he injured his hand, lie on the shelf in a warehouse for almost a month. Then one is dispatched to a dressmaker in Shrewsbury, another in York, a jeweller in Oxford. The final box, the smallest of the lot, still wrapped in rags from the floor of the Venetian glassworks, is sent by messenger to an inn at the north edge of the city, where it remains for a week. It is then carried outside by the innkeeper and, along with a parcel of letters and a packet of lace, is given to a man heading into Warwickshire on horseback.

p. 149

The fleas emerge and find new hosts…

[During the two-day journey], the fleas in the rags crawl out, hungry and depleted by their hostless stay in the wharfhouse. Soon, however, they are recovered, rejuvenated, springing from horse to man and back again, then out on to the various people the rider encounters along the way…By the time the rider reaches Stratford, the fleas have laid eggs: in the seams of his doublet, in the mane of the horse, in the stitching of the saddle, in the filigree and weave of the lace, in the rags surrounding the beads. These eggs are the great-grandchildren of the monkey flea.

p. 150

The fleas the rider brings to Stratford find Hamnet…

He delivers the letters, the packet of lace and the box of beads into the hands of an innkeeper on the outskirts of the town. The letters are delivered, one by one, to their recipients, by a boy [presumably Hamnet], in return for a penny.

p. 150

The fleas find Judith…

The box of beads is taken by the same delivery boy to a seamstress in Ely Street. She has an order for a new gown for the wife of a guildsman…that must have a bodice decorated with Venetian beads…

p. 150-151

The seamstress holds aloft the box. ‘Look,’ she says to the girl, who is small for her age, and fair as an angel, with a nature to match.

The girl clasps her hands together. ‘The beads from Venice? Are they here?’

The seamstress laughs. ‘I believe so.’

‘Can I look? Can I see? I cannot wait.’

The seamstress puts the box in her counter. ‘You may do more than that. You may be the one to open them. You’ll need to cut away all these nasty old rags. Take up the scissors there.’

She hands the girl the box of millefiori beads and Judith takes it, her hands eager and quick, her face lit with a smile.

A few days later, “Agnes is gripping [Judith’s] limp fingers…trying to tether her to life. She would keep her here, haul her back, by will alone, if she could.” (p. 164) And, she did. Soon thereafter, though, Agnes would say of Hamnet, “He is dead, he is dead, he is dead.” (p. 219)

A.L. Tarter

Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

NB:

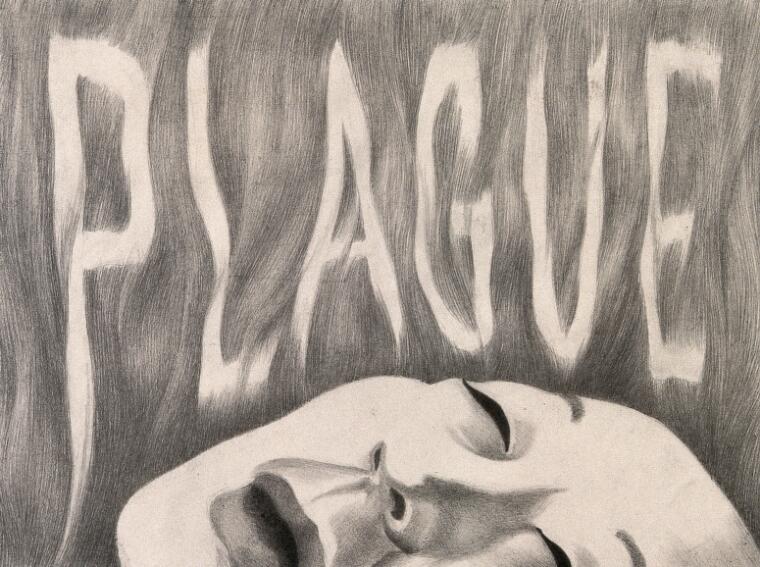

The title picture is, The path of infection of plague from rats via fleas to man, by A.L. Tarter from the Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

I cover the novel more broadly here.