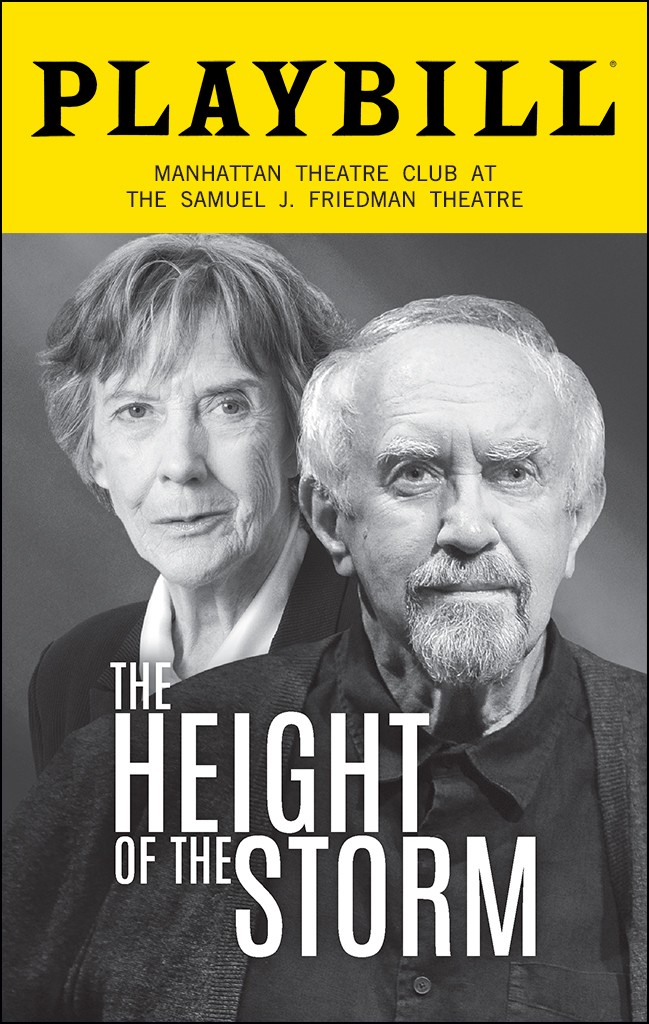

Playwright: Florian Zeller

Translator: Christopher Hampton

Director: Jonathan Kent

Performance venue: Manhattan Theatre Club at The Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

Performance dates: September 24, 2019 – November 24, 2019

Run time: 90 minutes

A Play Written with Jazz

With his play, The Height of the Storm, Florian Zeller returns to the subject of an older man descending into dementia. His earlier work was The Father, a 2016 Tony Award winning play that successfully conveys the dementia experience of the father character through a combination of dialog and staging. In The Height of the Storm, Zeller challenges the audience to experience André’s story structured with variations and interpretations of particular events that are unconventional and unexpected as expressed in the jazz idiom. That is to say that Zeller worked off of storylines, scripts, staging, and lighting common to standard plays in the same way the jazz composer works off melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and tones common to standard songs. He is writing with jazz.[i]

The Height of the Storm is thus the result of fusing two artistic genres to tell a story; in this case fusing dramatic theater and jazz. My objective is to describe how Zeller fuses jazz into this play, and how in the end, the play is as jazz does.

The Play

The play is set in the kitchen of a country house on the outskirts of Paris where André has lived for decades with his wife Madeleine and their two daughters, the older one Anne and the younger Élise, before they reached adulthood and struck out on their own. As the play opens, we see André staring at the garden through the kitchen window, and Anne entering to join him. “It’s no use waiting,” she says to him after he doesn’t react to her invitations to sit down. He is waiting for Madeleine to come in from the garden, but by most appearances, she has died a few days before. Anne tells him she encountered his diaries as she was going through his papers, and that his editor is interested in them. He turns and stares at her, but says nothing. “There are heaps of paper to sort through…But now all that needs organizing. That’s what I’m here for,” she tells him.

When André responds, he says nothing that has anything to do with what Anne has been talking about. He is not of right mind. He probably has dementia, which recent events are making worse. This brings Anne to the other reason she is there, “we need to find a solution…You can’t live here on your own. When there were the two of you, it was still viable. But now, it might be time to come up with something else. A different configuration.”

From this point the play diverges from a standard form in theater—a different configuration—as André eventually comes to grips with Madeleine’s death and his new circumstances. This is hard work for André, and Zeller makes it hard work for the audience to follow at times. Madeleine makes appearances throughout the play and goes about as if she were still among the living. A woman unknown to Madeleine and her daughters, who says she and André “know each other very well” from many years before, has a part. Élise brings a new boyfriend into the house. Zeller uses these characters (his musicians), and various scenarios (his scripting), to offer slants on the standard storyline to move the play along in ways that can engage and stimulate audiences, or that can confuse and alienate them.

As the play ends, all the characters are gone except for André and Madeleine who sit at the kitchen table. Madeleine talks about how they only need each other, and André talks about what would become of him without her. As she’s reassuring him that “I’m not going to let you down,” André finds a condolence card in his coat pocket and reads it, then realizes, finally, as the lights on Madeleine fade to black, it’s no use waiting.

The Play in the Jazz Idiom

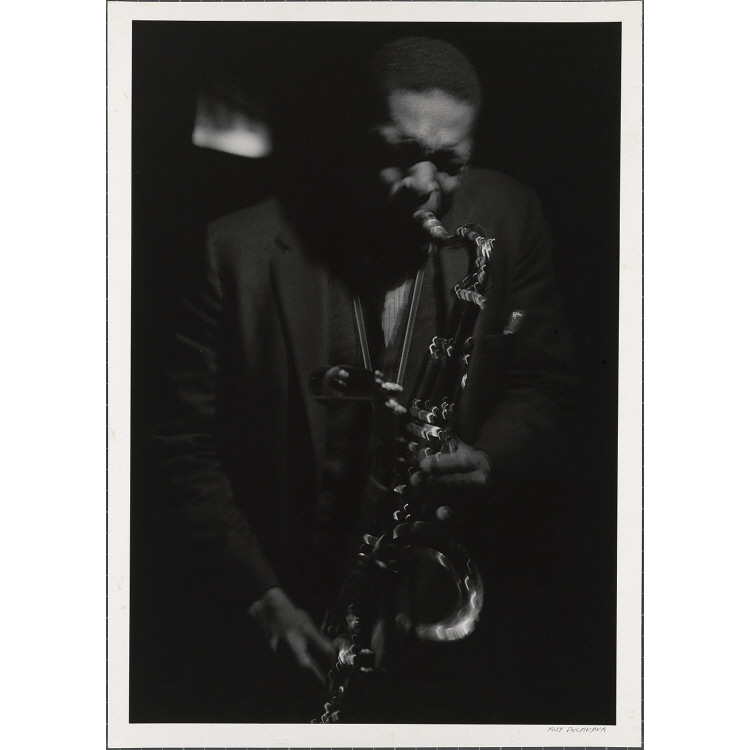

The jazz idiom refers to how jazz musicians take elements of a familiar song and alter them in different ways, to varying degrees, during certain intervals. The songs can remain easily recognizable and predictable during these departures from their original structures, like the Keith Jarrett Trio improvising on a standard (e.g., Autumn Leaves), or they can become increasingly less recognizable and eventually incomprehensible before they are familiar again, like late-career John Coltrane work. While it can be said that many genres of music depart from standard melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and tones, what distinguishes the jazz idiom from the other genres are characteristic methods and expressions, in particular its improvisational core.[ii] But, for Wynton Marsalis, “jazz musicians…almost always maintain the rhythm and harmonic structure of the melody when improvising.”[iii]

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution ©Roy DeCarava

As the playwright writing in the jazz idiom, Zeller is the composer, working with literary analogs of melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and tones, and structuring the roles for actors as “improvisations” off a standard storyline that are embedded in the script for them to follow closely. In contrast, jazz musicians bring their own, individual improvisations (i.e., storylines) to a composer’s structure of a particular song. Thus, the playwright writing in the jazz idiom provides the improvisation the idiom requires, and as such, is seeking the same opportunity John Coltrane said jazz musicians are seeking “for more plasticity, more viability, more room for improvisation in the statement of the melody itself,” but for the storyline itself instead.[iv] And like in jazz, when the play moves away at times from the recognizable storyline, the questions and tensions for audiences about where its going and why usually get resolved—that is where the art is.

Examples of the Jazz Idiom at Work in the Play

Zeller starts The Height of the Storm with the familiar and recognizable story of two daughters coming to the aid of their father who has just lost his wife (their mother) and who, they think, is not capable of living on his own. They begin to talk about what needs to be done and how to overcome all the challenges they will face with this task. But, Zeller early on introduces different ways of moving the story along, as if bringing in new harmonies, rhythm, and tones to a jazz composition. When Zeller departs from the original and recognizable storyline, what the audience perceives during some of these scenes is still recognizable, some of them are less familiar and hard to keep up with, and at other times they seem dissonant and even atonal—to use jazz terminology—before returning to the original and recognizable storyline.

Here are some examples from the play where the jazz idiom becomes evident to varying degrees beginning with the least departure from a traditional storyline in the play to the most unrecognizable. The increasing abstraction across these examples also resembles the layers of abstraction jazz musicians will often add to a song as it progresses.

The first example of where the play moves away from a standard storyline occurs early with the appearance of Madeleine coming into the kitchen after she had been out shopping and where she finds Anne and André. The two of them begin to trade dialog with Madeleine—first Anne speaks to Madeleine, then André speaks to Madeleine, and they continue to trade in this fashion—like jazz musicians trading musical ideas (improvisations) through their solos—to move this scene along. From these trades: we learn that Anne is going through André’s papers to assemble his unpublished works into a book; we hear of Anne’s difficulties with her philandering husband; and we get a hint that André may have had an affair in the past. Madeleine, as a deceased person, is an unexpected instrument in a conventional sense. These trades stop when Madeleine exits the stage and Élise picks up the conversation with André and comes back to the chorus of moving him into a better living arrangement in the more standard story trajectory.

The second example involves a scene that departs further away from a familiar storyline, while still remaining recognizable. Zeller uses the woman André knew long ago to describe his dementia and Madeleine’s fate. While calling on André at Madeleine’s invitation, this woman tells the story of her brother and his wife: “We had to put him in a nursing home. It was very painful… No one was expecting her to go first. The woman is telling the story of André’s dementia and Madeleine’s death in the same recognizable melody and rhythm as Madeleine would have used, but the woman’s voice, being different than Madeleine’s, again, represents a different instrument that produces a different sound and feel.

In the third example, the dialog and action leap away from the familiar and become dissonant, but with some concentration and imagination, audience members can follow the storyline. In one such instance, Zeller uses the woman who visits André to tell a part of his history that may have involved an affair with this same woman that produced a son. The familiar parts of a story about an affair are discernable as she recounts it to Madeleine, Anne, and Élise, but the way names and events are intertwined at times and unconnected at others leave the audience struggling to hang on to the story. As if Zeller anticipated (or intended) that the confusion in the audience would build a tension that needs to be relieved, he has Madeleine ask the question that empathizes with the audience’s situation, “Who is she talking about?” before she admits that she “doesn’t understand anything about this story.” For the same purpose, Élise says, and perhaps to also confirm for the audience that the jazz idiom is at work, “It seems to me we’re talking about something different from where we started out,” conjuring the way jazz musicians will sometimes drop in a few notes of a familiar melody in the midst of a seemingly unrelated improvisation. The conversation then returns to a more standard storyline form with a transition to dialog about their shared experiences with finding living accommodations for relatives with dementia, which are likely only too recognizable for many in the audience.

The last example highlights the most extreme manifestations of the jazz idiom in the play. In this case, the familiar or expected storyline is completely lost to the audience and scenes take on an atonal sensibility, that is, in the jazz idiom, a song in no key and with no mode, and to the unsophisticated ear, just noise. In one of these scenes, Madeleine speaks to Élise in front of André as if he had died. They don’t look at him, they don’t see him, they don’t acknowledge him:

I’m here! I…I…There, there’s my chair. I can still sit in it. And there are the flowers…I can still smell them. There’s the window. The door. The lamp. And me. I’m here. I…Look at me…

In abandoning the story’s structure entirely by making it possible for the audience to believe that it is Andréwho is dead, not Madeleine, Zeller is creating the confusion and tension for audience members that André experiences. This confusion and tension eventually resolves when the story comes back to a relatable form of the storyline as André finally realizes that Madeleine has died and he is without her just as jazz musicians often resolve the dissonance they can create from the basic structure of a song.

Program Rewards

Zeller offers his audiences insights on dementia and family relations in this play, but he makes them work for these insights. Zeller rewards this work, as composers of Western music do, when he provides the aesthetic satisfaction that comes from building tension through some degree of dissonance, and then resolving it into a sound familiar to listeners and comfortable to their senses. He may also be conditioning us to apply the jazz idiom to dramatic theater, or to combine other art forms, for greater pleasures and deeper insights.

Acknowledgments

Benedict Teagarden and Sam Petitti contributed mightily to my understanding of the jazz idiom and how best to describe it as it worked for this play. I doubt I did justice to their knowledge and experience; I appreciate their efforts and patience. Lucy Bruell made my attempt to convey how jazz is at work in this play much more readable than it would have been otherwise, as she always does with my writing.

A version of this essay is posted at the NYU Literature, Arts and Medicine Magazine site.

Endnotes

[i] Jarrett traces this quote to the person who wrote the liner notes to Coltrane’s album, Coltrane Live at the Village Vanguard Again!

[ii] I take these distinguishing features of the jazz idiom from Christine Recker’s M.A. thesis, Varieties of literary interpretations of jazz in American writings of the 1950s and 1960s (2006).

[iii] Quote is from Wynton Marsalis’ book, Moving to Higher Ground: How Jazz Can Change Your Life, Random House, 2009, p. 15.

[iv] I draw here from Michael Jarrett who characterizes what Zeller is doing to bring improvisation into this play as “writing with jazz.” (American Literary History, Volume 6, Issue 2, 1 July 1994, Pages 336–353.)

Also:

Figure credit: Jon Tyson on Unsplash