According to the Arts

The fatal shooting of a health care insurance executive in December, 2004 brings to mind four movies from the late 1990s and early 2000s. They depicted a building rage about new restrictions to health care coverage and the methods used to apply them, that spring from underlying structures and incentives embedded in US health care.

An Expected Event?

The fatal shooting of a health care insurance company executive in front of a hotel in Midtown Manhattan on December 4, 2024, is plausibly linked to the shooter’s rage about health care insurer practices of denying coverage for people in certain situations. Reactions to this event revealed a deep, seething antipathy across the country directed at the health care insurance industry, an antipathy that has existed for at least thirty years. The persistence of this hostility brings to mind four movies, three released in 1997 and one in 2002, for spotting a building rage in response to increasingly aggressive management health care payers were applying to coverage, and imagining what could happen as a result in specific scenarios, and in one case, a gun is drawn.

How it Starts

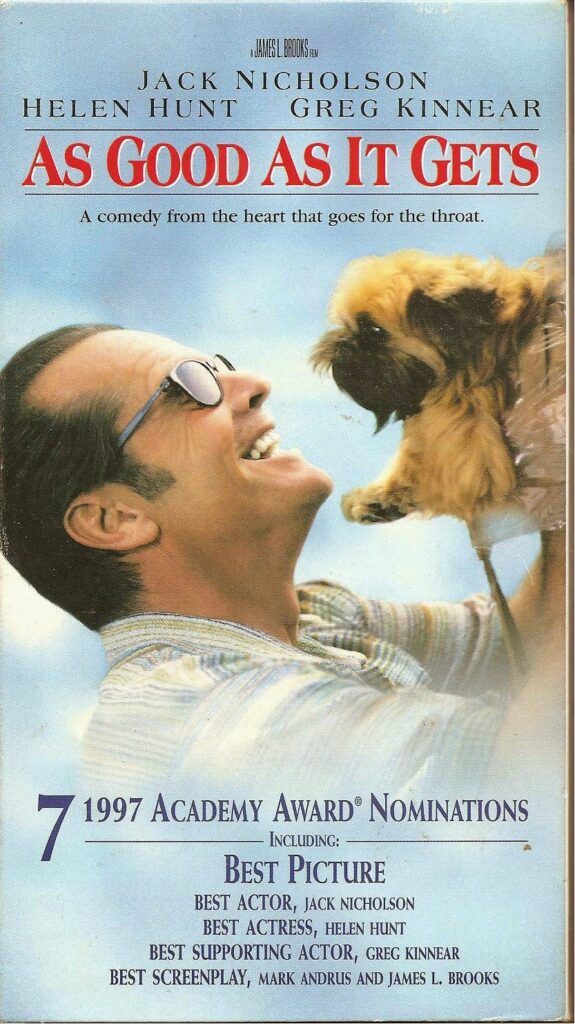

Fucking HMO bastards, pieces of shit…sorry.

This is how Carol reacts to the pediatrician who tells her the HMO should have covered certain tests for her suffering, asthmatic son. “Actually, I think that’s their technical name,” is the doctor’s response. This is from a scene in the 1997 movie, As Good As It Gets, directed by James L. Brooks. The movie won major awards from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts, Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and Screen Actors Guild, but it also won attention from the mainstream press for revealing a building rage about to boil over.

Ruthe Stein, from the San Francisco Chronicle, sensing the importance of the scene, wrote on December, 23, 1997,

As Good as It Gets may be the first movie to take on HMOs…Brooks strikes a chord when he has Carol use four-letter words to describe the HMO that has mangled her son’s case. The audience hoots and claps its approval.

The attention reached its cultural apogee in January, 1998 when President Clinton pointed to the scene as representative of real life while speaking at an event involving the Health Care Bill of Rights.

If As Good As It Gets was the first movie to take on the newly more aggressive management of health care costs, it wasn’t to be the only one, as others appeared around the same time or not long after. As creators in the arts often do, the makers of these movies were picking up on trends and signals before they were appreciated throughout society, and envisioning how they might play out in real life. Would these management practices just produce more public outbursts decrying them; would the health care payers self-correct; would state and federal governments step in with laws and regulations; or would health care providers and consumers eventually become inured and accept a new reality?

Worrying Trends and Alarming Signals

During the 1980s in the US, the rate of rise in health care costs were striking fear into health care insurers, governments, retirement systems, employers, trade unions, and individuals among others who were paying health care bills. Modifying payment structures and managing utilization were among the actions taken to address this problem, with the former affecting health care providers mostly (e.g., hospitals, physician practices) and with the latter affecting both providers and health care consumers. Health care consumers accustomed to filing insurance claims that payers reimbursed no questions asked (“indemnity plans”), started getting questions as payers began applying “management” to their health plans (“managed care”). Answers often determined whether particular claims were paid at all or how much would be paid, whether a physician or hospital was “in network,” whether a drug was “on the formulary,” or whether a particular procedure or use of a drug was approved for coverage.

The practical consequences of these and other management activities meant that patients were denied coverage for certain products and services altogether or pushed to a “preferred alternative,” asked for additional information before approval of a product or service (e.g., prior authorization), or made to find different doctors, clinics, pharmacies, lab services, or hospitals. Providers and health care consumers were assured, however, that these management activities “lower costs and improve health care quality.”

By the 1990s, these changes began to take hold. Increases in overall health care spending slowed, which was reflected in smaller increases in annual premiums. Thus began a rush to managed care plans from indemnity plans, especially for employer-sponsored health care plans. Enrollment in employer managed care plans reached 86% by 1998, when it had been 29% in 1988.

At these levels of penetration in the US population, and with the intensity of management activities ramping up, the unhappiness, and in some cases bad results they produced, got noticed. Mentions in mainstream media jumped from just under 500 in 1990, to about 4,000 every year from 1995 through 1999. Moviemakers noticed, too.

Movies Raging Against the Managed Care Machine

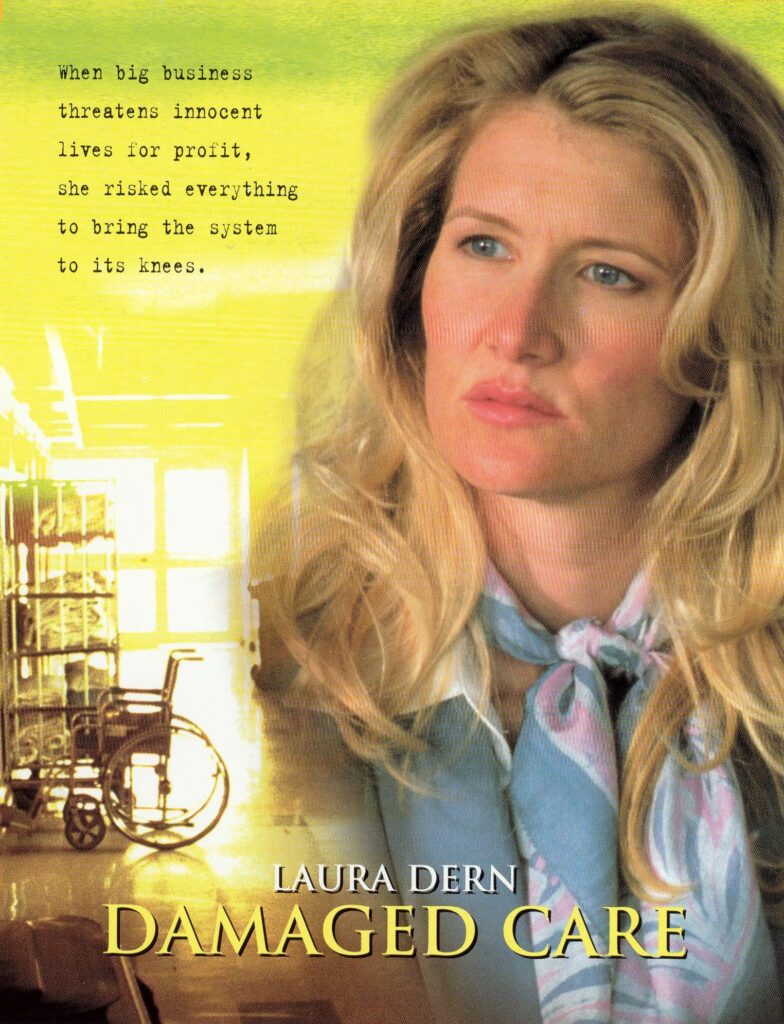

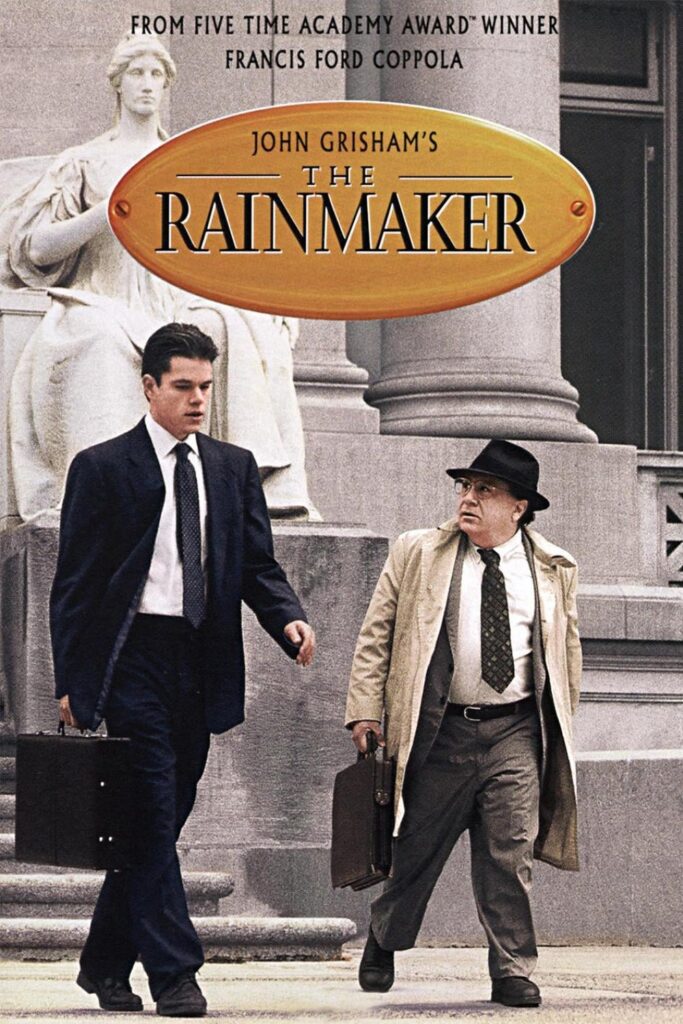

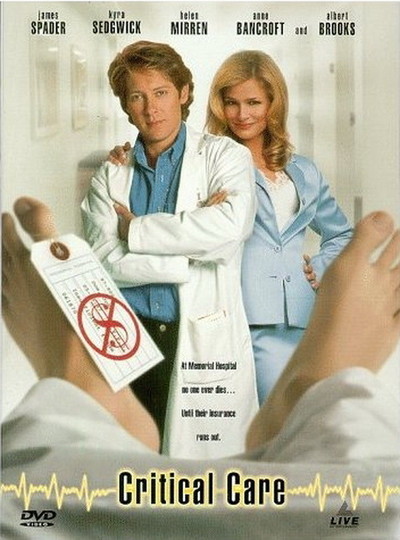

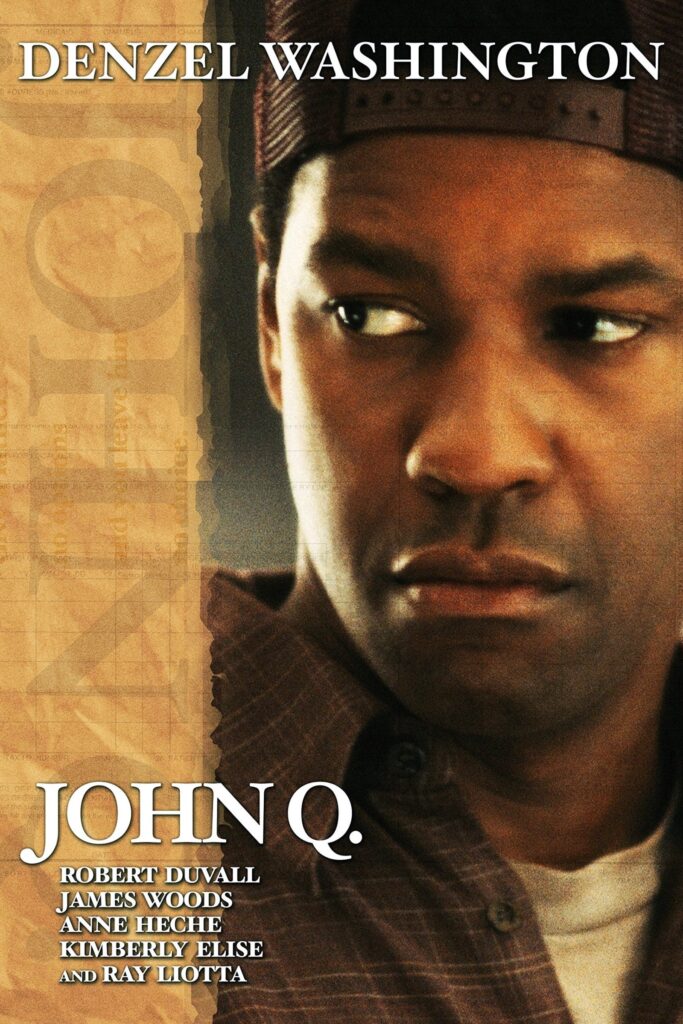

The first movies getting attention for featuring real or imagined scenarios in which managed care activities had serious consequences were released in 1997, and were, As Good As It Gets, Critical Care, and The Rainmaker. In 2002, John Q was released with others yet to come. (1)

As Good As It Gets (1997, director – James L. Brooks). The movie mostly concerns the relationship between an author with obsessive compulsion disorder and a waitress who the author depends on for a routine set of practices around his breakfasts. A side story involves the waitress’ young son who has severe asthma. At one point he needed certain tests, but his health plan refused coverage. This situation led to the scene in which the boy’s mother reacts to this news in a way that attracted widespread public attention. The scene lasted for less than a minute, yet its effect on the image of managed care activities continued for years.

The Rainmaker (1997, director – Francis Ford Coppola). The movie plot involves a scam operation posing as a health insurance company. A young lawyer, fresh from passing the bar exam, takes on the company through the case of a plaintiff. The plaintiff is a young man who has a form of leukemia that can be successfully treated, but would kill him otherwise. The insurance company denies coverage for the needed treatment, and denies seven subsequent appeals. The lawyer eventually ascertains how the company denies all claims as a matter of course. Although a judgment is made against the company, it declares bankruptcy and goes out of business, thereby vitiating the settlements awarded. The patient dies. The movie is known for a line said by the lawyer’s assistant fueling the growing public sentiment at the time: “There’s nothing more thrilling than nailing an insurance company.”

Critical Care (1997, director – Sydney Lumet). The setting for the movie is mostly in a hospital critical care unit. Like in As Good As It Gets, a particular scene feeds the fury to come about managed care. A resident physician taking care of a terminal patient who has been clear about not wanting to continue treatments that only prolong suffering, argues with a senior physician and mentor about the advisability of putting the patient through yet more futile interventions. With his guard down from a combined state of inebriation and dementia, the senior physician tells the resident that the patient is fully insured and is thus a source of guaranteed revenue. He goes on to explain the economics (and immorality) driving these decisions.

[With HMOs] we get paid not to perform medical procedures. It’s a little like when the government pays the farmers not to grow crops. However, with insurance we get paid to perform medical procedures. Do you understand the difference?

On that basis, and that basis alone, he demands that the resident proceed full speed ahead.

With this scene, the moviemaker is going further than pointing to just the managed care organizations as the source of rage, but also to the health care providers who can spot opportunities for self-dealing. Viewers already sensitized to managed care activities could become even more worried, incensed, or nihilistic about the situation.

John Q (2002, director – Nick Cassavetes). About the same time John Q. Archibald’s full time factory job is cut in half, along with his health insurance, his son collapses from heart failure while playing in a Little League Baseball game. After a cardiologist tells John about their son’s need for a heart transplant and the financial requirements that he can’t meet, a nurse they asked why his heart condition had not been detected before tells them, “HMOs pay the doctors not to test. That’s how they keep costs down.” This comes up again when John asks the cardiologist how it could be that his son’s condition had never been discovered. An accompanying intern chimes in saying,

HMOs pay their doctors not to test. That’s their way of keeping costs down. Let’s say Mike did need additional testing and insurance says they won’t cover them. The doctor keeps his mouth shut and, come Christmas, the HMO sends the doctor a fat-ass bonus check.

The surgeon qualifies the intern’s assertion as possible but unlikely.

Try as he might, John Q cannot come up with the $75,000 down payment. The hospital administrator will not put his son on the transplant list and he is released to be taken home where he will die. John pulls out a gun and takes the emergency room hostage. No one is killed, no one is shot, and a solution is found in the end. However, the movie raised the level of rage to one that produces the possibility of gun violence.

What Lies Beneath

Nearly thirty years have passed since these movies depicted the rising rage coming in response to aggressive measures directed at managing health care costs, especially when they involved restrictions on certain products and services health care providers ordered and patients expected. Did these movies get it right? In large measure, they did. Management activities became more aggressive over the years and indeed many of those became a reality for some. As a medical affairs executive in a large pharmacy benefit company before, during, and after these movies were released, I witnessed (and fought) these and others as bad or worse (with the exception of gun violence).

These movies also got some of the motivations for the highlighted management activities right when linking them mostly to capitalistic principles and business objectives, despite marketing taglines promoting as their primary interests the health of the people they serve. Less explicit in these movies is the underlying political preferences over several decades for privatization of health care in the US. The products and services covered, the provider networks available, the costs borne by health care consumers, and other components of health care are left to for-profit, commercial entities. They can also be left to nonprofit health care organizations that behave similarly in the pursuit of the “margin” they need for their mission. Even state and federal government agencies cede these kinds of activities to the private market for some segment of their beneficiary populations (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid).

What the movies did not consider, and would not be expected to, is that cost management activities applied to health insurance coverage are not the province of health insurers and managed care organizations only. Self-insured employers, for example (for-profit and nonprofit), often choose to pay for health care directly instead of paying premiums to insurers, and so have an interest in taking actions to lower costs for their own profitability. Some, but not all by any means, will therefore encourage or demand that their third-party administrators (e.g., health care insurers, pharmacy benefit managers) carry out aggressive cost management practices like those seen in the movies. (2) In serving payer clients in these roles, third-party administrators share accountability for the clinical and ethical consequences of their involvement in cost management actions.

Viewers could take from the movies that any management of health care costs are prima facie inappropriate, unethical, and even illegal. But when considered from broader understandings of heath care financing, they could temper their reactions when taking into account the ways health care insurance provides access to health care that wouldn’t be possible without it. One way is just by spreading the risk for these costs over large groups making coverage available to people who do not have access to it through other means. And, for another, the need to set limits for coverage because of the insatiable demand for it creates opportunities for interjecting reasonableness and fairness into coverage policies and cost management practices. (3) Thus, the movies should not be used in calls for eliminating health care insurance management practices altogether, but rather for demands that they be reasonable and fair for the people affected.

Will it Ever End?

The movies helped to identify the problems early, and also to bring attention to them, even if the problems were used only as plot points. Professional health organizations and consumer advocates among other affected constituencies pushed legislatures and regulators into creating laws and rules about how health care insurance cost management activities must and must not be run. And accreditation agencies reacted as well in creating new standards and criteria tied to coverage policies and management practices. These measures helped some, but the rage remains, and is maybe even intensifying to a level the movie John Q anticipated.

Notes

These movies were available on various streaming services at the time of posting.

Health care insurance companies can serve their payer clients as either the actual insurers taking risk for the payers’ health care costs through premiums they receive or as third-party administrators for self-insured employers on a fee-for-service basis.

For details on how “reasonableness and fairness” can be worked into health care insurance and management, see:

Daniels N, Sabin JE. Setting Limits Fairly: Learning to Share Resources for Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Wynia MK, Schwab AP. Ensuring Fairness in Health Care Coverage: An Employer’s Guide to Making Good Decisions on Tough Issues. New York: AMACOM, 2007.

Pearson SD, Sabin JE, Emanuel EJ. No Margin, No Mission. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Daniels N, Teagarden JR, Sabin JE. An ethical template for pharmacy benefits. Health Affairs 2003;22:125-137.

Russell Teagarden and Dan Albrant discuss these movies and how they anticipated anger and frustration resulting from managed care activities on episode 27 of their podcast, The Clinic & The Person.

A version this post is at medhum.org.