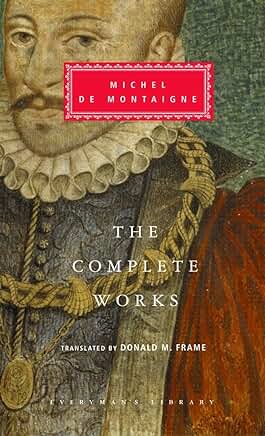

In an earlier blog entry, I covered how Montaigne suffered from kidney stones—”the worst of all maladies”—but he nevertheless asserts benefiting from them. Among the benefits he claims across several essays in The Collected Works (Everyman’s Library), were fearing death less and appreciating good health more between events. From his experience with kidney stones and various other health problems, Montaigne had occasional encounters with doctors and general health care services available during his lifetime (1533-1592). From these encounters, he formed opinions about health care and how he would manage his relationship with it. His opinions derive from an extensive experience with his own illnesses, of which he had many: “no one can furnish more useful experience than I, who present it pure, not at all corrupted or altered by art or theorizing. Experience is really on its own dunghill in the subject of medicine, where reason yields it the whole field.” (p. 1007)

The doctors and health care services Montaigne critiques shared the same objectives as those of the twenty-first-century, even though the levels of medical sophistication and support differ by a monumental degree. Yet, many of Montaigne’s observations echo today. To sample Montaigne’s views on doctors and health care services he encountered, I draw from these three essays: Of Experience, Of Moderation, and Of the Resemblance of Children to Fathers. I group his observations under: finding the right balance; worrying about the reliability of medical knowledge; and engaging doctors and health care services.

Finding the Right Balance

Montaigne’s general approach to staying healthy and recovering from illnesses never involved giving doctors or health care services complete control over him. He had learned that a combination of patience with ailments and acceptance of inevitability have their own benefits:

I have allowed colds, gouty discharges, looseness, palpitations of the heart, migraines, and other ailments to grow old and die a natural death within me. I lost them when I had half trained myself to harbor them. They are conjured better by courtesy than by defiance. We must meekly suffer the laws of our condition. We are born to grow old, to be sick, in spite of all medicine. (p. 1017)

More specifically, Montaigne anchored the balance he sought for his health to his habits. He wants neither health problems nor health services interfering with his life, and indeed he thought that such interference was its own cause of problems: “It is for habit to give form to our life, just as it pleases; it is all-powerful in that.” (p. 1008) In other words, just taking us away from those habits have possible independent deleterious health consequences.

Montaigne recognizes the difficulty achieving this balance because doctors “keep prescribing for sick men a way of life not only new, but contrary: a change that a healthy man could not endure.” (p. 1014) He offers a specific example of how “to be subjected to the stone and subjected to abstaining from the pleasure of eating oysters are two troubles for one.” (p. 1014) He returns often to his objections to treatments that upend routines or habits, and quotes the sixth-century, Etruscan poet, Maximianus, in summing up the predicament people can find themselves in when engaging doctors and health care services.

Obliged to wean our souls from things on which they thrive,

We give up living, just to keep alive,

Should they be said to live who cannot breathe free air

Or see the light, without oppressive care? (p. 1014)

The balance Montaigne sought between his lifestyle and health care needs when they arose, which seems to privilege letting nature takes its course, aligned him with the element of Stoic philosophy wherein happiness comes from “living in agreement with nature,” and enduring all that comes with it. For Montaigne, then, he would suffer considerably before seeking medical attention. But there were other reasons for his reluctance.

Worrying about Reliability of Medical Knowledge

Montaigne argues for strong and vital health care services given that “health is a precious thing, and the only one, in truth, which deserves that we employ not only time, sweat, trouble, and worldly goods, but even life; inasmuch as without it life comes to be painful and oppressive to us.” (pp. 703-704) At the same time, he is aware that the science behind “our preservation and health is unfortunately the most uncertain, the most confused, and agitated by the most changes.” (p. 709) This reality impaired his ability to assess whether engaging with doctors and health care services for specific purposes would interfere with his habits and routines for acceptable reasons, and in particular, for good outcomes.

When Montaigne considered availing himself of health care services, he approached the decision with a high degree of doubt: “I do distrust the inventions of our mind, of our science and art, in favor of which we have abandoned nature and her rules, and in which we know not how to maintain either moderation or bounds.” (pp. 703-704) He knows his uncertainty of the science is shared with doctors from the “perpetual disagreement that is found in the opinions of the principal ancient masters and authors of this science…and inconsistencies of judgment which they foster and continue among themselves.” (p. 709)

When Montaigne gives greater detail on the roots of his worry about the reliability of medical knowledge, he describes many of the elements underlying health care decisions today.

God knows how difficult is the knowledge of most of these details; for how, for example, shall he find the proper symptoms of the disease, each disease being capable of an infinite number of symptoms? How many controversies and doubts they have among themselves over the interpretation of urines! Otherwise whence would come this continual altercation that we see among them over the diagnosis of the malady? How should we excuse this mistake into which they fall so often, of taking marten for fox? In the illnesses I have had, however little difficulty there was, I have never found three of them in agreement. (p. 712)

Woodcut

National Library of Medicine – Images from the History of Medicine

He doesn’t leave the issue there. Within his skepticism for any certainty physicians during his time convey about particular diagnoses and treatments, lies the components of knowledge acquisition embedded today in biomedical research. He points in particular to hypothesis testing, replication of findings, and publication bias (the problem of negative results going unpublished).

…even if the cure should be performed, how can he [the doctor] be sure that this was not because the illness had reached its term, or a result of chance, or the effect of something else he had eaten or drunk or touched that day, or the merit of his grandmother’s prayers? Moreover, even if this proof had been perfect, how many times was the experiment repeated? How many times was that long string of chances and coincidences strung again for a rule to be derived from it?

When the rule is derived, then by whom? Out of so many millions there are only three men who have undertaken to record their experiences [i.e., Parcelsus, Fioravanti, and Argenterious]. Will chance have lighted precisely on one of these? What if another man, and a hundred others, have had contrary experiences? Perhaps we would see some light if all the judgments and reasonings of men were known to us. But that three witnesses, and they three physicians, should lay down the law to mankind is not reasonable, unless human nature had deputed and chosen them and declared them to be our arbiters by express power of attorney. (p. 722)

Maybe Montaigne would be assuaged somewhat if he were living now and seeing how individual practitioners, health care institutions, payer organizations, and government agencies have adopted research and technology assessment methods designed to guide diagnosis and treatment decisions. But, only somewhat, probably, if he looked more closely at current factors degrading the reliability of medical knowledge, of which I take up in another blog entry.

Engaging Doctors and Health Care Services

Montaigne held complicated and generally negative views of doctors specifically and health care generally, some of which related to challenges achieving the balance he sought and the problems with reliability of medical knowledge. When taken together, his basic contention was that doctors did too much and knew too little.

The arts that promise to keep our body in health and our soul in health promise us much; but at the same time there are none that keep their promise less…The most you can say for them is that they sell medicinal drugs; but that they are doctors you cannot say. (p. 1008)

These promises, Montaigne further notes, become “tyrannical” in the way they can capture “poor souls who are weakened and beaten down by sickness and fear.” (p. 707)

Even though Montaigne was often harsh in his judgements of doctors, saying once, for example, “a man would have to be preternaturally blind not to feel that he runs a great risk in their hands,” he allowed that his criticism may be directed more at the profession than any individuals. (p. 709) In doing so, he situates the medical profession in the same place as any other “occupation” serving the general public.

My quarrel is not with them but with their art, and I do not greatly blame them for making their profit of our [ignorance], for most people do so. Many occupations, both less and more worthy than theirs, have no other foundation and support than in the folly of the public. (p. 719)

Montaigne admits that he could very well submit himself to the care of doctors, but not necessarily as an act of a sound mind.

I do not say that I may not be carried away someday by that ridiculous notion of committing my life and my health to the mercy and government of the doctors. I may fall into such a madness; I cannot answer for my future firmness…It will be a very evident sign of a violent sickness. My judgment will be extraordinarily unhinged. If impatience and fear win this victory over me, people may infer from it a very fierce fever in my soul. (p. 724)

And so, while Montaigne allows that he may seek health care and doctors on certain occasions, he will not allow that he trusts those decisions any more than he trusts his doctors.

Woodcut

National Library of Medicine – Images from the History of Medicine

Montaigne’s Harmony

In today’s world, Montaigne would find that health care and its practitioners have advanced as he probably hoped it would and more than he could have imagined. However, he would still be challenged to meet his primary objective of achieving the right balance between health care consumption and his preferred lifestyle (i.e., habits), especially in the U.S. Health care in a capitalist society is as voracious as any industry, and can be as tyrannical as Montaigne worried about in his time, if not more so. It beckons us through television, radio, internet, and even billboards, and is still making promises—ever more often and ever more fantastical—that cannot be met. People could spend a good majority of their time (and money) in the health care system when they are not discerning about the value of any health care service and the tradeoffs needed in their lives. Indeed, contemporary essayists have made this point recalling Montaigne five-hundred years later.

Modern medicine has produced miraculous, live-saving results. And it has produced methods for preventing illness and restoring health for less serious problems but ones that cause discomfort and self-limited conditions. However, in nearly every case there are costs in the forms of money, time, and opportunities, and thus as Montaigne said during his time, and that he might say again now: “Our life is composed, like the harmony of the world, of contrary things, also of different tones, sweet and harsh, sharp and flat, soft and loud.” (p. 1018) His is a poetic way of urging us to consider all dimensions of our lives—our world—when engaging health care services.

Edited by Lucy Bruell.