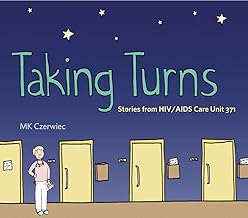

MK Czerwiec

University Park, Pa

Graphic Mundi

The Pennsylvania State University Press

2021

According to the Art:

The book is a graphic memoir covering MK Czerwiec’s time mostly as a nurse in the HIV/AIDS unit at Illinois Masonic hospital in Chicago, Illinois from 1994 until 2000 when the unit closed. It provides a personal context for one of the most serious and complex medical calamities in decades, and in a form that adds value to conventional forms of biomedical texts and teachings.

Synopsis:

With a degree in English and Philosophy, MK Czerwiec was intent on becoming a writer, but she found that her “attempts were just dreadful,” and that the best job she could get “was making copies and sorting tax forms.” (p. 2) That would not do. She began thinking about nursing school. Czerwiec had done a good job taking care of her father for the seven years following his stroke before he died, and her mother’s career as a nurse was an inspiration. With a promise from her brother, a high school chemistry teacher, that he would get her through chemistry and math, she enrolled.

The book is a graphic memoir covering Czerwiec’s time mostly as a nurse in the HIV/AIDS unit at Illinois Masonic hospital in Chicago, Illinois from 1994 until 2000 when the unit closed. Also covered is some of the time leading up to her assignment on the unit and some retrospection many years later with a former patient, fellow staff members, and her social network.

Czerwiec describes the thinking behind creating a special unit for HIV AIDS patients and contrasts its design, operation, ethos, and pathos with more typical inpatient units. She depicts some of the challenging aspects of caring for HIV/AIDS patients and tells the stories of certain patients, one of which she became particularly close with, maybe even too close, with their personal relationship and off-duty get togethers: “I think it’s time for me to stop being Tim’s nurse.” (p. 114) Also getting attention in the book is Czerwiec’s frightening needle stick incident; counseling she sought with the “psychiatric liaison to Unit 371”; and developments in HIV/AIDS treatments, including “highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)” that became available, and eventually obviated the need for the unit altogether.

A subtext in the book concerns how Czerwiec came to graphic medicine. While working on Unit 371, she “wrote in a notebook, usually stories from the previous night’s work…Writing helped clear my head.” (p. 75) She later added painting as a way to deal with grief. Eventually, as the unit was winding down and closing, she recalls: “my writing morphed into whiny journal entries, painting wasn’t working anymore. Images alone felt inadequate. I needed to find a new way…or perhaps I needed to let a new way find me.” (p. 165) She started playing with a comics format, and “Whoa. This comic ends in hope…Didn’t see that coming.” (p. 166)

Since then, Czerwiec has attracted an audience. She has built a considerable oeuvre, and has become a prominent figure in graphic medicine.

Analysis:

Graphic medicine has taken on some of the attributes of a genre. It is taught in health care professions, is featured in professional journals (e.g., Literature and Medicine), publishes a journal (Graphic Medicine Review) and is supported by a professional organization (Graphic Medicine International Collective). A steady stream of graphic medicine media in many formats is produced. Czerwiec’s book, Taking Turns, is illustrative of the genre.

Czerwiec tells how Unit 371 was purposely designed and operated as an atypical hospital floor in order to meet the intense and specialized needs of HIV/AIDS patients during the peak years of the crisis: “What I’ve learned over time is that there absolutely are boundaries on Unit 371, but they are thinner than in other settings. Appropriately so.” (p. 91) She includes a drawing of the unit with all its patient rooms, therapy rooms, kitchens, lounges, patios, nooks, and crannies (p. 34). A certain logic attaches to describing this atypical unit in an atypical format such as Czerwiec’s graphic memoir. As a case in point, because of the high mortality of AIDS at the time, the unit allocated a certain number of beds to hospice care.

In several instances, Czerwiec shows how the graphic medicine medium offers advantages over more conventional literary genres. One in particular is a graphic showing how managing all the treatments and procedures as ordered for a single patient is not possible. She draws an IV pole with eight hooks all attached to various infusions: some antibiotics to be given every six hours and some every four hours (there will be mix ups); toxic infusions that require time and attention to address, time that is needed for other infusions (there will be serious reactions); and twenty-four-hour infusions that cannot be administered with any other medications making several IV lines necessary (or fingers crossed). (p. 36)

Another set of illustrations shows how plans for an orderly shift quickly disintegrate. Czerwiec draws a chart showing each of her patient’s names and what she needs to do for them and at what times. She draws a second chart in which she superimposes unplanned exigencies and emergencies over her original chart, showing intervening diversions such as: “your patient is having a seizure”; “Andy pulled his IV line, there’s blood everywhere”; and “He’s not regaining consciousness. Let’s get him an ICU bed.” (pp. 42-43)

In a full-page, single-panel graphic, Czerwiec explains the complications of HIV/AIDS. She places a patient standing in the center, and with text boxes pointing to the involved anatomical location, she lists the diseases and complications most commonly resulting from HIV/AIDS. Across the bottom of the graphic, Czerwiec notes, poignantly: “Often several of these things will happen at once.” Making the further point about patient involvement in their their own care and as sources of their own medical information, the patient pictured is given a voice bubble reminding readers of one other important disease of AIDS. (p. 9) In this one graphic, she offers as much information, albeit in a truncated form, as a biomedical textbook chapter on the complications of AIDS.

Dismissing Czerwiec’s book and graphic medicine in general as gimmicky or unserious might be expected of hardcore biomedical professionals and followers, as I once was myself. Those who adhere to that view, however, will deny themselves perspectives and knowledge not as available from conventional biomedical texts and teaching. Taking Turns makes this point with one of the most serious medical calamities in decades.

(from https://comicnurse.com)

Also:

More of MK Czerwiec’s work can be seen at her website, comicnurse.com, and at the Graphic Medicine International Collective website.

An interview with MK Czerwiec about Graphic Medicine and her memoir on the podcast, The Clinic and The Person is posted here.

Edited by Lucy Bruell