Andrew Scull

Cambridge, Massachusetts

The Belknap Press

2022

494 pages (86 pages of notes)

According to the art:

Andrew Scull documents how psychiatry’s quest for safe and effective treatments for mental illness over the past century and a half has not produced any notable successes and left many people severely and fatally harmed along the way. The lessons learned apply to medicine more broadly today, and likely forever more.

Synopsis:

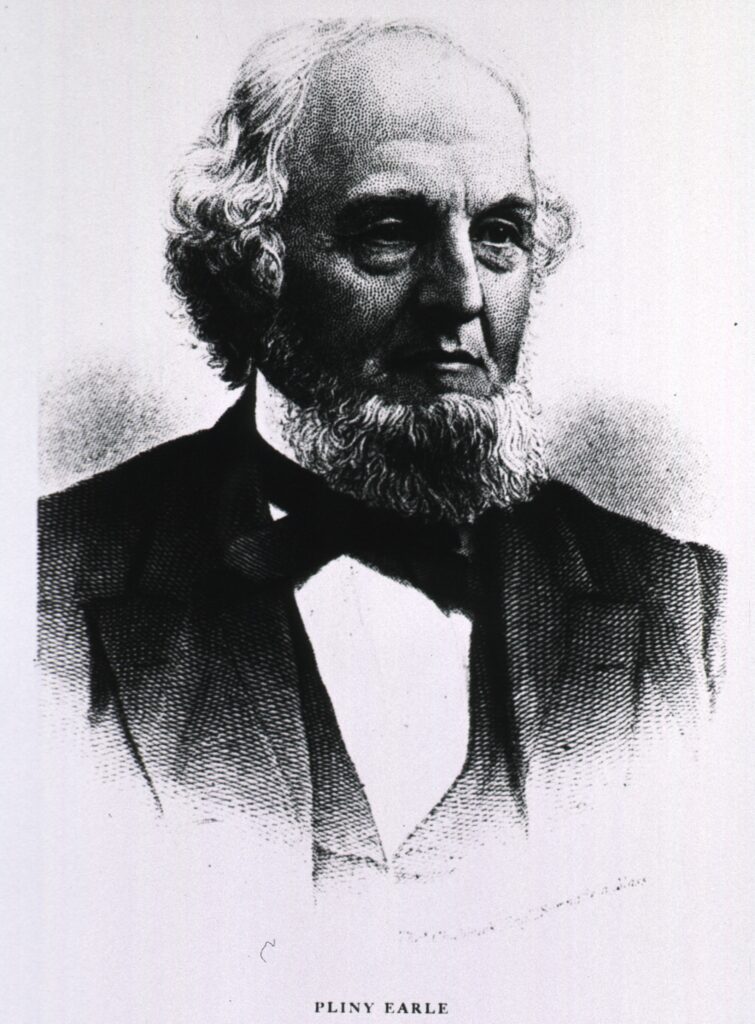

Pliny Earle II was an American psychiatrist and a founder of the American Medical Association, the New York Academy of Medicine, the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane, and the New England Psychological Society. Towards the end of the book, the author, Andrew Scull, quotes him saying in 1886,

In the present state of our knowledge, no classification of insanity can be erected on a pathological basis, for the simple reason that, with but slight exceptions, the pathology of the disease is unknown…Hence…we are forced to fall back upon the symptomatology of the disease.

p. 349

Scull then appends, “Nearly a century and a half later, nothing, it seems, had substantially changed.” (p. 349) In this book, he explores the sociological and historical events, fashions, and dogma in psychiatry from the beginning of the “asylum era” in the 1820s to the present time as he seeks to learn how this can be so.

In seeking answers, Scull applies “a skeptical assessment of the psychiatric enterprise,” allowing for the possibilities that its efforts to improve the lives of people with mental illnesses made them worse instead. (p. ix) Based on an assumption that psychiatrists shared goals “to relieve suffering and, more ambitiously, to restore the alienated to the ranks of the sane,” Scull structured his analysis around four central questions: “how have psychiatrists sought to realize these goals; how have [they] attacked the problem of mental illness; what weapons have they chosen and why; and have those treatments succeeded in relieving suffering and curing those consigned to psychiatrists’ tender mercies.” (p. ix)

The book is separated into three parts, mostly in chronological order. The first part covers the era in which asylums dominated; the second part covers the constituencies and events shaping psychiatry more as a medical profession, and as “deinstitutionalism” begins; and the third part covers the intensified-but-doomed efforts of psychiatry to align with medicine in form and practice by establishing a pathophysiological basis for mental health problems that could lead to safe and effective treatments.

In the first part of the book, Scull gives considerable attention to early “therapeutic” interventions. He lists just a few of the favored procedures in the book preface:

Inducing fevers by deliberately infecting patients with malaria, by injecting horse serum into spinal canals to induce meningitis, or by placing patients in diathermy machines that broke down the body’s homeostatic mechanism, attributed to Dr. Julius Wagner-Jauregg.

p. xiv

Surgically removing teeth and tonsils, followed by the evisceration of stomachs, spleens, cervixes, and colons, attributed to Dr. Henry Cotton.

Using newly-discovered insulin to create artificial comas that often brought patients to the brink of death, attributed to Dr. Manfred Sakel.

Inducing artificial epileptic seizures, first with drugs, then with electricity passed through the brain, attributed to Dr. Ladislas Meduna.

Severing of brain tissue, either through surgical operations on the frontal lobes or by thrusting an ice pick through the eye socket into the brain—so-called transorbital lobotomies, attributed to Dr. Walter Freeman.

He provides more examples and detail about these and like procedures, all of which began in the asylums, and some of which saw use outside of them and even into the twenty-first century. Scull also reveals: how the psychiatric community, especially within asylums, supported the procedures, and how many leading health care institutions eventually adopted them: how professional organizations lauded them (e.g., developer of lobotomies awarded 1949 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine); how mainstream media promoted them; and how eventually they fell out of favor and became seen as the atrocities they were.

The second part covers psychiatry as it begins expanding away from asylums and advanced mental illness. Mental hygiene and particularly psychoanalysis come into the picture, and resistance among institutional psychiatrists pushed these methods into private settings. At the same time, psychiatry was becoming part of university-based medical school education and attracting private and government funding. Scull describes in detail how psychoanalysis grew to prominence and how World War II and the resultant immigration of European psychoanalysts affected the field and its evolution in these directions. These new directions and participants resulted in opposing camps that jockeyed amongst each other for dominance in position, acceptance, and funding. One of the major results of all these movements was the inexorable decline and end of institutional psychiatry, and “so it was that an alternative version of malign neglect became public policy, dressed up in the raiment of reform.” (p. 247)

The last part of the book covers the efforts psychiatry makes towards becoming a branch of medicine. Psychiatry had landed on mental illness as a problem of the brain rather than of the mind. So, like other medical fields, it operated on the theory asserting a pathophysiological basis is at work in mental illness and corresponding remedies would reveal themselves. Scull points to the introduction of antipsychotic drugs (e.g., chlorpromazine) in 1954 as a watershed event in this movement. Indeed, in recognizing the significance of the shift from psychosurgery (e.g., lobotomies) to psychopharmacology that the drug represented, its actions were described as providing a “medical lobotomy.” (p. 273) He examines the profession’s efforts at creating diagnostic schemes (e.g., Diagnostic Statistical Manual), developing community care models, and finding pathological mechanisms for mental illness using advanced neuroscience technologies and genetic analytical methods.

Scull concludes this part noting psychiatry has made few advances since the beginning of the asylum years and has harmed many people. He points to the absence of convincing pathophysiological mechanisms for mental illness as a cause this predicament. “The symptoms and suffering will not disappear, but if they do not correspond to a distinctive disease, then trying to discover the cause or causes of that non-existent disease will necessarily be a fruitless task.” (p. 357)

Scull admits that some patients have benefitted from psychiatric interventions, even if for a little while.

It would be a serious mistake not to acknowledge that for some patients, antipsychotics and antidepressants provide real relief from some of the symptoms that cause so much distress and suffering…Yet it must also be pointed out that, for many patients, the therapeutic interventions the profession relies on have only limited efficacy.

p. 358

Overall, Scull is unsparing in his assessment of what psychiatry offers. “For the present, we need to be honest about the dismal state of affairs that confronts us rather than deny reality or retreat into a world of illusions. Those, after all, are classically seen as signs of serious mental disorder.” (p. xvii) For this state of affairs, though, he does not leave governments off the hook.

The closing of asylums coincided with the abandonment of any serious public effort to ameliorate the sufferings of those gravely disabled by mental disturbances of all kinds…In a society that valorizes the market as a universal solvent, and that attributes failure to the shortcomings of the individual, those with serious mental illness face a harsh future. The malign neglect that has for nearly three-quarters of a century constituted public policy in this arena was not instituted at the behest of psychiatry, though with few exceptions the demise of public psychiatry drew little protest from with the ranks of the profession.

p. 385

Pliny Earle II died in 1892. If he were back today, he might be pleased his assertion that a pathophysiological basis for mental disorders is needed still holds, but nevertheless horrified seeing people with mental illnesses not much better off than when he died.

Analysis:

Though Scull never mentions Michel Foucault by name, through lines exist from his book to Foucault’s Madness and Civilization and The Birth of the Clinic. The through lines are easily appreciated and serve to support the arguments made in this book.

In Madness and Civilization, Foucault constructs a history of insanity since the time madmen wandered the countryside and represented one end of the human behavior continuum (“village idiots”), through the period when authorities confined the mentally ill and other unseemly types (e.g., criminals, indigents) together, and until they were separated into asylums. Once in asylums, people were classified based on how others perceived the variability in their behaviors (e.g., schizophrenic, depressive), because these perceptions were not associated with any pathological explanations. Scull begins his analysis here into how psychiatry developed around people housed in asylums and classified based on perceptible manifestations of mental illness.

In The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault describes the transformation medicine made once “pathological anatomy,” the science linking knowledge about physical and functional alterations of organs and tissues to particular disease states. Before, only signs and symptoms the body surface presented served more for classifying than discerning health problems. Now certain signs and symptoms with a pathological basis could be used to classify particular health problems, and hence the shift from “classificatory medicine” to “clinical medicine.” From then on, clinical medicine operated from a premise that diagnostic processes and treatment regimens should derive from known, or at least plausible pathophysiological mechanisms of disease.

Scull argues that despite intense efforts over a century and a half to establish a pathological basis for mental illnesses as clinical medicine had, none was found. As a result, psychiatry could not emulate medicine in its own evolution. Psychiatry was stuck with behavioral characteristics that represented, as Thomas Szasz saw them, “problems with living.” Perceiving mental illness in any other way, he goes onto say, “was nothing more than a myth, an imaginary entity conjured up by his fellow professionals that has no biological reality.” (p. 299) Without these pathophysiological frameworks, psychiatrists have been free to conjure all sorts of ideas about causes and invent all sorts of interventions, many of which range from useless to horrific and deadly.

Expanding the boundaries of what psychiatrists could conjure was the absence of any agency available to the people who would be affected. Scull makes the point repeatedly about the vulnerability of people subjected to these interventions. First, as he notes, “virtually all of these were disproportionally visited on women, though the best data we have indicate that mental illness afflicts men and women almost equally. The pattern of disparate treatment is indisputable.” (p. xiv) Scull attributes this maldistribution to “gendered prejudices,” wherein men perceived that “women’s minds…were much more closely linked [than men’s] to their peculiar biological nature,” i.e., female. (p. 148)

Second, Scull notes that the problems many people with mental illness have with reasoning vitiates the validity of informed consent prima facie. But much of the more heinous activities took place at a time when informed consent was not uniformly available, accepted, or required, and in some cases where it existed in some form, ignored. “As a general rule…Cotton ignored objections from patients and their families and was quite open about doing so. Such protests were, he claimed, short-sighted and ignorant.” (p. 85)

And third, families had strong incentives for submitting family members to these interventions in the interest of helping them recover full function, or in their own interests to regain a manageable and peaceful family life. In effect, people subjected to these confinements and interventions were not seen as patients or as informed subjects, but as victims.

The absence of constraints around how mental illness could be understood and treated, combined with the absence of constraints around standards of care and ethical obligations, unleashed a Promethean hubris during the asylum era that exists to a degree still. Scull beseeches the psychiatry profession on this account.

It would help enormously if psychiatry were to be more honest about the limits and imperfections of its knowledge, as well as less committee to a single approach to the problems with which it grapples. Humility and open-mindedness are deeply desirable qualities, but they are in short supply.

p. 385

Beyond some of the interesting and horrifying history Scull’s book provides, a good use for it is to see psychiatry and its history as a proxy for the medical professions generally. The use of psychiatry exaggerates the general picture, but the other medical professions have similar histories and problems differing only in degree. The pathophysiological basis for the diseases they confront are in many cases only explanatory models occasionally leading to abjectly wrong diagnoses and treatments that over time come to be seen as ineffective, dangerous, and even barbaric, witness radical mastectomy for breast cancer.

The philosopher, John Huss, asks: “Should we worry about the reliability of medical knowledge?” Scull’s book is a full-throated and well-documented affirmation that we should worry, a lot, and we should always worry based on human fallibility and folly alone, before we even consider all the shenanigans associated with medical knowledge development and dissemination. A practical implication of Scull’s work, then, is that we should approach health care knowing what is accepted as standard medical practice today, maybe even miraculous today, could be considered abhorrent in the future.

Also:

Scull never mentions Thomas Kuhn, but a through line also exists to his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, in particular as it gives theoretical form and historical examples concerning how shifts from one approach to another took place in psychiatric practice. A full explication of Kuhn’s theory of how science advances is beyond the scope of this piece, but it does well in accounting for the major changes in approaches to mental illness over the decades, for example, from psychobiology to psychoanalysis, from psychoanalysis to psychosurgery, from psychosurgery to psychopharmacology, and from institutionalization to community care.

The story of Walter Freeman and ice pick lobotomies are depicted through a fictional figure in the movie, The Mountain, and as the subject of the PBS documentary film, The Lobotomist. Henry Cotton’s ideas around tooth extraction, tonsil removal, and abdominal and gynecological evisceration as treatments for mental illness are briefly depicted in the tenth episode of the first season of the television series, The Knick.

Maggie O’Farrell novel, The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox, provides literary portrayals of how young girls and women who were quirky, headstrong, oppositional, inconvenient, or embarrassing were institutionalized and subject barbaric treatment during the asylum era.

The book is featured in an episode of the podcast, The Clinic & The Person.