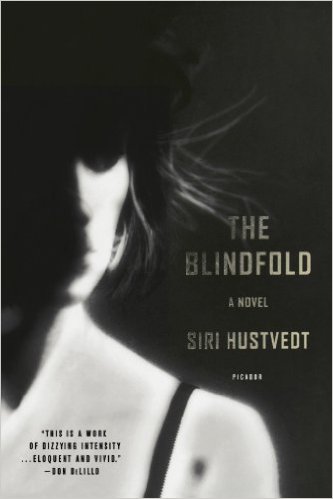

Siri Hustvedt

New York

Picador

1992

221 pages

According to the Art:

The book comprises four sections that can work together or independently of one another, but across all of them are scenes in which the main character experiences migraine headaches that provide perspectives on the physical suffering they can cause, the nature of relationships migraineurs can have with health care providers, and some of the social implications associated with chronic migraine headaches.

Synopsis:

Iris Vegan is a young graduate student at Columbia University in New York City during the late 1970s. She arrived there from Minnesota in pursuit of a PhD in English Literature. The book comprises four sections, which are not sequenced chronologically, and could stand apart from one another. In fact, according to her biography, two of these sections were published in literary magazines as short stories. Iris is the first-person narrator of them all.

Each of the four sections centers around Iris’s relationship with a particular person, in one case as part of a job, another case as social, once both job-related and social, and once as a ward mate in a hospital. The two primary throughlines traversing the sections are Iris’ struggles common among many graduate students—poverty, despair, hopelessness—and migraine headaches. Some characters make appearances in more than one section, and events in some sections are referenced in others. Nevertheless, readers can discern a beginning, middle, and end, roughly.

As this site is concerned with literary depictions (among other genres) of specific health problems and clinical scenarios, I focus here on the attention given to Iris’ migraine headaches. Migraines occur in the book within different scenarios providing perspectives on the physical suffering they can cause, the nature of relationships migraineurs can have with health care providers, and some of the social implications associated with chronic migraine headaches.

Analysis:

The author, Siri Hustvedt, does not make Iris’ migraine headaches pivotal to any storylines. Even in the section where Iris is placed in a hospital for treatment, the story is mostly about her relationship with a wardmate. But her migraines are present enough to give readers a sense for how they affect sufferers in various ways.

In one scene where Iris is consulting a migraine specialist, Hustvedt portrays the terror the migraine aura can cause, shows how a specialist can reduce the event into cold, unemotional, and impersonal medical language, and the impact both can have on the patient.

I could see that Dr. Fish was restless, and although I wanted to explain that the feeling of completeness, of perfection, was essential to the story, I rushed on. ‘But as soon as I stepped inside my apartment, I felt a tug on my left arm, just as if someone had yanked it hard. I lost my balance and fell down. I was so dizzy and sick to my stomach that I didn’t get up for a long time. While I was sitting there on the floor, I saw lights, hundreds of bright sparks that filled up half the room, and after they disappeared, I saw a big, ragged hole in the wall. That hole scared me to death, and the strange thing was that I didn’t experience it as a problem with my vision. I really thought that part of the wall was missing. I don’t know how long it lasted, but after the hole was gone, the pain started.’

p. 93

Dr. Fish picked up the microphone. ‘The patient suffered a scintillating and a negative scotoma.’

This ferocious editing had a peculiar effect on me. As the interview continued, I mumbled, coughed, forgot words, and lost track of what I was saying…I felt that if I could articulate my illness in all its aspects, I might give a trained ear the clue that would make me well, but my words were always inadequate.

Interactions like this one can push migraineurs away from health care providers or can make them reluctant to report the true state of their health. Iris exhibits this response when she describes how she approached her migraine specialist thereafter.

Every week, I went to Dr. Fish, and every week, I looked better to him, less pale, less tired. He interrupted me more frequently and summarized my complaints in an increasingly optimistic light. I couldn’t see or feel these changes myself…the truth is I participated in the deception…Concealing illness from a physician is absurd, but I couldn’t bear to be seen for what I was—a person going to pieces.

p. 94

Maybe Iris would have been more forthcoming if her physician didn’t interrupt her so much. Hustvedt apparently knew from experience or intuition about how frequently physicians interrupt patients. She could also know of empiric data from a frequently quoted study reporting physicians interrupt their patients eleven seconds on average after they began talking.

Iris’ reluctance to admit she suffers from migraine may stem also from broader forms of denial and nihilism associated with migraine. Concealing migraine headaches is common among migraineurs. Many of them want to avoid questions people often ask, like, how bad could it be, it’s just a headache. While describing herself to a friend who told her she has asthma, Iris starts with, “I have no chronic illnesses that I know of.” (p. 127) Migraine is mostly an episodic event, but it occurs chronically; Iris is splitting hairs to keep her migraine condition private. She came clean when she was admitted to a hospital for migraine control, and when she reported that she had migraine headaches “for seven months almost without respite.” Nihilism is also at work when she says: “As a migraineur, I had low status…and headaches had little clout on the neurology ward.” (p. 91)

Hustvedt makes the trepidation migraineurs can demonstrate in engaging with heath care providers all the more tragic with Iris’ telling of the extracorporeal nature migraine auras can manifest and the world-altering perceptions they can produce.

I have never been able to write off these experiences as aberrations that are purely neurological, because while they are happening, I am convinced that I am seeing the truth, that the terrible fragility and absence I feel is the world—stark and unclothed. That nakedness is irretrievable. It is left behind in the raw voiceless place that exists beyond the muttering dreams of everyday life, where you cannot ask to go but must be taken.

pp. 67-68

Migraine aura is the source of Iris’ suffering for the most part. Not much is said about the pain that usually follows. Of one of her more striking migraine pain events she said, “My pain had ballooned: it filled my whole head and seemed to enlarge my skull as it grew. I was all head then, a female Humpty-Dumpty with four useless limbs.” (pp. 106-107) This description calls to mind the “Syndrome of Alice in Wonderland,” J. Todd discerned in 1955, from individual case studies of migraine resembling scenes in the book, Alice in Wonderland. The author, Lewis Carrol, was known to suffer from migraine headaches.

The Blindfold was published in 1992, which was around the time new and more effective medications became available for the treatment of migraine headaches (i.e., “triptans”), and so what Iris went through with her migraine headaches might have been different from that time on. However, triptans are not used to prevent migraines, just to treat them. Newer drugs—monoclonal antibodies—have become available more recently. Yet for many people with migraine headaches, the experience remains much the same as Iris’.

Hustvedt knows of where she speaks as it concerns migraine headaches. She, herself, has suffered from them through her life. She also knows life as a graduate student in English at Columbia University after having been born and raised in Minnesota. When we root for Iris to overcome her migraines and for her success in graduate school, we root for Hustvedt. We don’t know what became of Iris, but we know that Hustvedt became an important writer and thinker whether or not her migraine headaches dissipated.

Also:

This novel was featured along with Joan Didion’s essay about her migraine experience, In Bed, in an episode of the podcast, The Clinic & The Person, that I cohost with Dan Albrant and with executive producer Anne Bentley.

A comparison of biomedical and other literary texts describing migraine is here.

Reference to Syndrome of Alice in Wonderland: Todd J. Syndrome of Alice in Wonderland. CMAJ 1955;73:701-703.