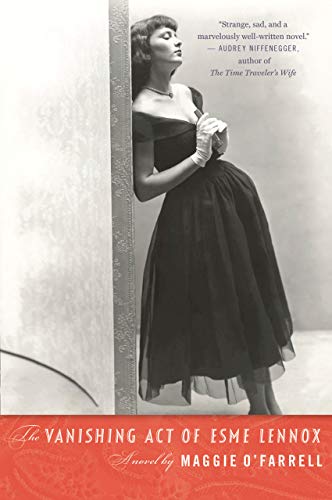

Maggie O’Farrell

New York

Harvest

2008

245 pages

According to the art:

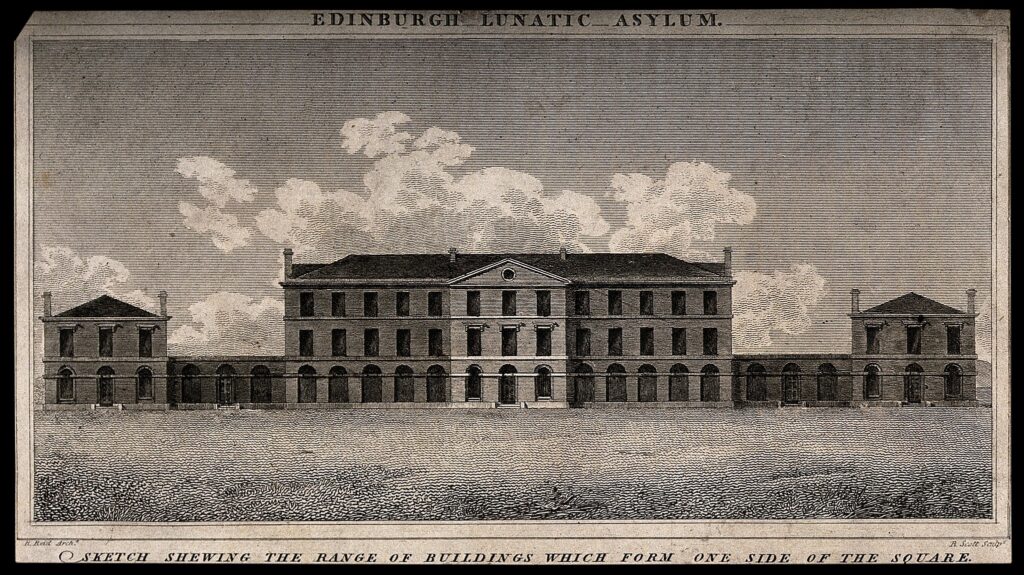

A central concern of the novel is the role and operation of asylums in Western nations during most of the twentieth-century, with particular attention to how asylums affected the plights of women. The story is a literary representation of the period for asylums that corresponds with social historian Michel Foucault’s analysis in his book, Madness and Civilization.

Synopsis:

Euphenia (“call me ‘Esme’”) Lennox didn’t fit well in her family or in the family social circles. She was tall, she had curly hair, she was fiercely independent, she was outspoken, she was ambitious, she was obstinate, and she was obsessive among the other attributes and characteristics known to her family. “You never knew, with her, what was going to happen from one minute to the next,” Esme’s sister, Kitty, said about her. (p. 127) And what happened next was sometimes horrifying, often unacceptable, and always embarrassing for the family given where and when the novel takes place.

The place and time of the novel offered the socially-conscious, aristocratic, British family a solution; in 1938, they committed Esme to an asylum—“Cauldstone”—at the age of sixteen. Henceforth, she was never to be spoken of; she had vanished and would remain as such for “sixty-one years, five months, four days” when a family member two generations on was notified of her imminent discharge. (p. 76) The asylum was closing down, and consequently Esme became the ward of her assumed great niece, Iris. Before then, neither of them knew of each other’s existence, and so Iris was surprised to learn that she was on record as the family contact for Esme at the asylum. Esme was just as surprised.

Esme was born in India, probably in 1922, while her British parents were stationed there. Also there is Kitty, who is six years older, and her younger brother, Hugo, a toddler at the time. Esme is a problem child from the beginning, “impossible, disobedient, unteachable, a liar” according to the tutor the family hired. (p. 26) These traits are all common enough in young children. It was Esme’s reactions to two particularly searing and traumatic incidents, among a few others, that landed her in the asylum.

One incident was the death of Hugo from typhoid when Esme was probably around twelve years old. Her parents were away and their caretaker had also succumbed. Esme was left alone holding her brother’s corpse for days in the house library. She was in shock. “She wouldn’t let them take Hugo. They had to prise him from her.” (p. 42) Esme was given no succor or help for her trauma—her mother would neither speak to or look at her. Worse still, no one was to speak of Hugo’s death, but Esme could not comply. As a result, as Kitty relates,

Father had to take Esme into his study…[and] when she came out she looked very pale of face, very agitated, her lips trembling and her arms folded. She never spoke of him again…She seemed to take it the way she took everything: excessively hard.

p. 92

From then on, Kitty recalled, Esme had moments when she became “perfectly still, motionless, in fact. Barely breathing. She would be staring into space and I say staring when in actual fact she didn’t seem to be looking at anything at all. You might speak to her, call her name, and she wouldn’t hear you.” (p. 93) She was catatonic.

The other incident occurred after the family had returned to Scotland. Esme was sixteen when she was forced to attend a social gathering where she could attract the attention of potential suitors. The attention she attracted, however, was from the boy her family wished for Kitty. Esme reluctantly agrees to dance with this boy who glides her off the floor into an adjacent room and rapes her. Upon seeing her mother the next morning, Esme “opened her mouth and she screamed, she screamed, she screamed.” (p. 169) Her mother called the doctor and told him “something about how she was sick to her back teeth of these fits of shouting and raging.” (p. 173) With Kitty providing additional evidence of Esme’s mental instability, her father took her to the asylum kicking and screaming.

Kitty was told never to mention Esme’s name again. And she didn’t, until Iris had some questions for her about who she thought was the great aunt she had never heard about. The answers unravel remaining mysteries around family lineages, in particular how Iris is related to Esme and Kitty, and what led to the deadly consequences of Esme’s long and unjust confinement.

O’Farrell tells the story through a third-person narrator, interspersed with a combination of random and prompted recollections of Kitty, whom, at the time, Iris knows as her grandmother. Kitty exhibits a degree of dementia, which Iris calibrates as: “Some things she remembers quite clearly and others are just gone. Generally, she’s stalled at about thirty years ago.” (p. 206) O’Farrell’s use of a fractured narrative and literary style heightens the suspense and accentuates the many revelations and injustices.

Analysis:

A central concern of the novel is the role and operation of asylums in Western nations during most of the twentieth-century, with particular attention to how asylums affected the plights of women. Esme’s time in the asylum mirrors the time from when people who were considered sources of embarrassment and shame to a family were committed for behaviors classified under vague and nonspecific terms—hysteria, mania, hypochondria, and melancholia—to the time asylums were decommissioned and closed over concerns they cause more harm than good.

Esme’s story is a literary representation of the period for asylums in Western countries that corresponds with social historian Michel Foucault’s analysis in his book, Madness and Civilization. O’Farrell creates a scene illustrating the range of behaviors and circumstances that resulted in admission to the asylum in the 1930s. Iris wants to know why Esme was put in the asylum, and so she obtains authorization to review her records. A clerk gives her several volumes of patient records to search through from around the years Esme was probably committed. Before she finds Esme’s records, she comes across the records of several others.

Iris reads of the refusals to speak of unironed clothes, of arguments with neighbours, of hysteria, of unwashed dishes and unswept floors, or never wanting marital relations or wanting them too much or not enough or not in the right way or seeking them elsewhere. Of husbands at the end of their tethers, of parents unable to understand the women their daughters have become, of fathers who insist, over and over again, that she used to be such a lovely little thing. Daughters who just don’t listen. Wives who one day pack a suitcase and leave the house, shutting the door behind them, and have to be tracked down and brought back.

p. 58

O’Farrell highlights how people committed may have had no say in the matter. Kitty reports that the doctor who came in response to Esme’s screaming episode after the rape said to her, “we are going to take you somewhere for a wee rest, how would you like that?” She, of course, in her way said she wouldn’t like it at all, and then his voice went stern and he said, “we are not giving you a choice so—.” (p. 172) Another time Iris reports what she has learned about asylums to her love interest: “Imagine. You could get rid of your wife if you got fed up with her. You could get shot of your daughter if she wouldn’t do as she was told.” (p. 64)

O’Farrell goes further in describing the cruelty and banality that could accompany the actual process of bringing someone to the asylum. Esme’s father drives her to Cauldstone. Upon arrival, “he doesn’t speak as he gets out, as he and the doctor wedge her between them and walk her across the gravel and up the steps to a big building.” After Esme is forcibly turned over to a nurse,

[She] sees her father stoop briefly over the drinking fountain, wipe his mouth with his handkerchief, then walk away over the chess squares of marble towards the door…He descends the steps, he buttons his coat, he puts on his hat, he glances up towards the sky, as if checking for rain, and then he disappears.

pp. 175-176

Reflecting the changes in characterizing and managing behaviors during the six decades of Esme’s residence, Iris reads from her records: “Euphemia has had a variety of diagnoses from a variety of…of professionals during her stay at Cauldstone.” (p. 35) Kitty said that “dementia praecox [the term used for behaviors eventually classified as schizophrenias] is what they said for her. Father told me that when I asked him once.” (p. 174)

When mounting social, cultural, and political pressures forced asylums into closures during the latter half of the twentieth-century, many people in the asylums were returned to families or turned out into the streets (“sidewalk psychotics”). They could be managed better and more humanely in clinics, or they were ready to function successfully in society, so the wishful thinking went. O’Farrell insinuates that asylums suspiciously found their patients rehabilitated and prepared enough for release at just about the time they were to close. In one scene, Cauldstone staff seek to assure Iris that Esme is prepared for discharge. “My colleagues and I have worked closely with Euphemia during our recent schedule of Rehabilitation Programmes. We are fully convinced of her docility and are very confident about her successful rehabilitation into society.” Iris challenges the credibility of their assessment. “And I suppose that this opinion of yours has nothing to do with the fact that this place is being closed down and sold for its land value?”

The response: “Are you willing to take her?” (p. 35) If O’Farrell wanted the novel to critique family and societal abuse of past and current approaches to mental health, then she probably would have had Iris refuse to take Esme and leave her to a fate on the streets as so many others have been to this day. But, O’Farrell had more of a story to tell that required Esme’s participation, and so Iris took Esme, only to learn that she wasn’t insane, she was mad.