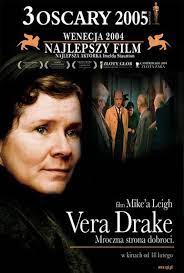

Vera Drake

Mike Leigh – writer and director

Les Films Alain Sarde, Film Council, Inside Track Productions – production companies

US release – February, 2005

Run time – 125 minutes

In the film Vera Drake, the director Mike Leigh is asking viewers to consider more than whether abortion is right or wrong prima facie. He is forcing viewers to bring in motive as a qualifying factor to the rightness and wrongness of abortion. Motives of the nature given to the character Vera Drake are rarely considered in contemporary mainstream debates about abortion.* Leigh’s background suggests that he might have wanted to draw attention to this aspect as Taubin reveals in a review of the film.

For Leigh, the starting point of Vera Drake was, without question, the issue of abortion. He dedicated the film to his parents, “a doctor and a midwife,” and, in an interview, he told me that because his parents’ practice was largely in a working-class neighborhood, he was aware, since childhood, of women who performed illegal abortions.

Leigh isolates the aspect of motive so viewers can see motive in this film as transcending the subject of abortion and making it a metaphor to investigate motive and virtue. In particular, Leigh is permitting the viewer to reference Kantian moral philosophy as a way to understand the importance of motive. As characterized by Kemerling, Kant specified that:

…actions are morally right in virtue of their motives, which must derive more from duty than from inclination. The clearest examples of morally right action are precisely those in which an individual agent’s determination to act in accordance with duty overcomes her evident self-interest and obvious desire to do otherwise.

Early in the film, Leigh shows Vera helping neighbors and family who cannot even manage to make a cup of tea or retrieve a biscuit. She goes about this work cheerfully but no less dutifully. She is not shown to make any claims of self-interest. These people need help. This is not so hard for the viewer to grasp. But then Leigh shows Vera performing abortions “[to help] out young girls in trouble.” Here is where Kant’s moral philosophy emphasizing the role of motivation in determining virtue gets tested.

Kant concluded that the expected consequences of an act are themselves morally neutral, and therefore irrelevant to moral deliberation. The only objective basis for moral value would be the rationality of the Good Will, expressed in recognition of moral duty.

Leigh isolates Vera’s motivation (or duty to her). The young girls in trouble are shown in shots that convey desparation. They are shown in poorly lit, stark, stuffy rooms that no one with money would choose to live in by themselves let alone with a child to raise. They are shown as scared and in much need of succour. To further isolate the desparation that Vera addresses, Leigh juxtaposes the case of Susan, who because she has enough money can get an abortion after date rape in a relatively safe, discreet, and dignified manner. Vera is not needed here even though she works as a domestic where Susan lives. Susan is frightened, but she is not desparate. Vera could not justify performing an abortion on her even though the consequences are the same for her and as they are for the poor young girls in trouble, i.e., abortion to Vera is a morally neutral consequence, it is helping out desparate girls that matters.

The foundation for Vera’s Kantian moral philosophy is shown to the viewers through a question posed to Vera by the inspector about her own history of seeking an abortion when she might have been a young girl in trouble. Leigh has Vera answer this question without speaking. The camera is kept on Vera’s face for a seeming eternity as viewers watch her try to say yes but can never get it out. Her face seems to show the horror of reliving her trouble, a horror that burned into her soul a motivation to help similar girls in trouble without regard to consequence.

Leigh gives the film viewers other perspectives on the moral philosophical theme in the film when they are shown several scenes where friends and family members are clearly perceiving (through shots of various admiring glances) or remarking on Vera’s basic goodness. Vera’s husband Stan is reminded often by his brother about how lucky he is to have Vera, and Stan himself often remarks that Vera is as “good as gold.” When Vera’s family learn that she has been performing abortions and why, viewers see that her moral philosophy may not be shared. Her son, Sid, rejects motives as sufficient and focuses on the consequences, i.e., killing unborn babies. Leigh makes this character a tailor, a person concerned with how people look without necessarily being concerned with why they look a certain way. Stan is shown in stunned silence. The viewers’ attention is kept squarely on Stan as if they can see the wheels turning in his head. He is wondering whether good motives can be justified in the case of abortion. In the end he sides with Vera, but not necessarily from an endorsement of her moral philosophy but rather from fidelity. Leigh is not letting viewers think that Kantian moral philosophy is to be accepted without challenge or argument.

Critics might argue that this film cannot be read as abortion as metaphor serving Kantian moral philosophy because then motivations can be used to justify killing abortionists to save babies every bit as well as to justify helping out young girls in trouble. However, the metaphor can work when consequences are morally neutral, i.e., motives are isolated from consequences.

Leigh’s personal background suggests that he is sympathetic to young girls in trouble and the women who want to help them out. A literal read of the film Vera Drake can generate that view. However, the film is created in a way that also permits a deeper investigation of motives from Kantian moral philosophy.

*Though not about abortion, the TV situation comedy series, The Good Place, aired originally from 2016 to 2020 on NBC, and then became available on Netflix, explores intentions as a key determinant of the moral rightness of a given action.