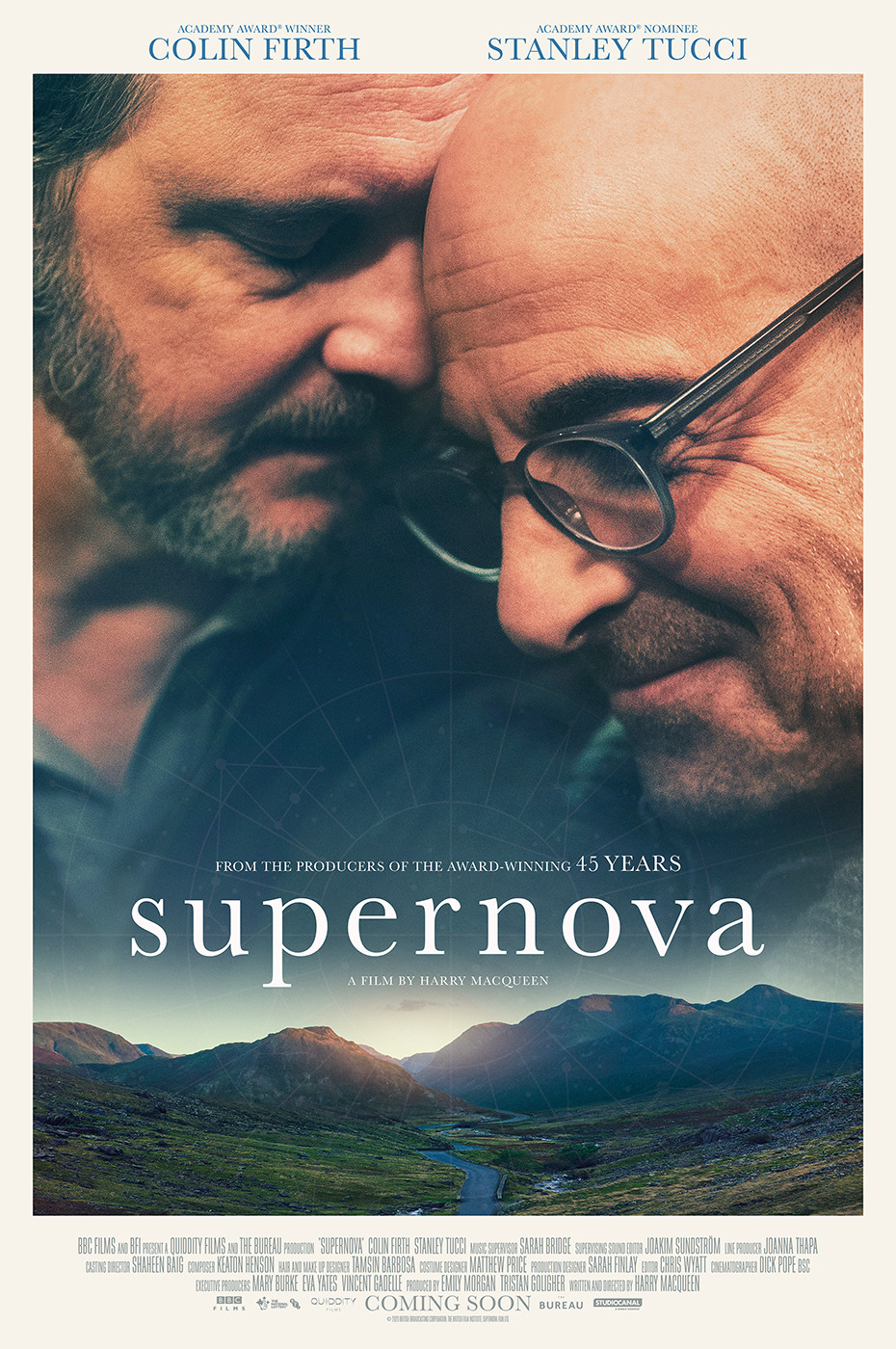

Harry Macqueen – writer / director

British Film Institute and BBC Films – production

2020

Streamed on Hulu

Runtime – 93 minutes

According to the art:

The movie shows how a long-term gay couple faces the onset of dementia as any heterosexual couple does, but does not consider how it could be different.

Synopsis:

Sam and Tusker hit the road. They head for the calm and bucolic English Lake District in their aging camper van. Sam (played by Colin Firth) and Tusker (played by Stanley Tucci) are aging also; they look in their sixties. Their relationship, too, is aging having lasted thirty years, but the nature of it is changing with Tusker showing signs of dementia.

Tusker, still quite able in many ways, arranged the trip ostensibly around Sam’s piano concert at a small venue before returning to major concert halls. He included a visit to Sam’s sister’s house and stops at some of their favorite places in the Lake District. But along the way we begin seeing Tusker’s intentions of not returning home. Although his dementia is in an early and only subtly discernable stage, he neither wants to live the remainder of his life in oblivion nor burden Sam with his care: “I want to be remembered for who I was and not for who I’m about to become.” As a novelist, no longer being able to read or write is torture enough. He’d rather go out like a supernova.

Much of the trip, which is most of the movie, comprises the conversations Tusker and Sam have about how they will manage “this thing” (they rarely use the word dementia). They start with diverging views accompanied by anger and fear, eventually converging on an agreed path in peace and with acceptance.

Analysis:

Movies featuring dementia abound, and some to great acclaim such as The Father, which came out the same year as Supernova. Most of these movies follow the plights of heterosexual couples or the surviving spouse of one. Are they the same experience?

Sam and Tusker’s plight is portrayed as it generally takes shape for heterosexual couples. They experience the same anxieties, fears, sadnesses, and forebodings. “I want to see this through, with you, to the end,” Sam tells Tusker. Surely the experience of gay and heterosexual couples facing dementia and death can be the same in many instances, and that is the apparent approach the filmmaker, Harry Macqueen, chose. Fair enough. However, Macqueen could have retained much of Sam and Tusker’s experiences common to heterosexual couples while also considering their particular circumstances to inject more pathos and drama into the movie, which it needs.

Sam and Tusker were in their sixties in 2020 meaning that the two of them likely came of age during the AIDS epidemic when no treatments were available. We can imagine that they both suffered searing losses of many dear friends and lovers. The memory of these losses could have manifested in Sam’s reactions to Tusker’s fate, and could have been a component of their conversations. Likewise, Sam and Tusker might have also witnessed—and remember—the rapidly progressive and devastating AIDS dementia complex, which here, too, could have been linked to Tusker’s motivation for avoiding dementia at any cost.

Macqueen does a service showing how gay couples can suffer the same effects of dementia as heterosexual couples. In some ways, though, the experience for gay couples who had experienced AIDS could conceivably be different. Just how it could be different remains available for another filmmaker.