If the soul is where feelings and emotions reside, then the soul is where the Norwegian expressionist painter, Edvard Munch, visited and is the source for many of his paintings, particularly those he grouped as a series he called: The Frieze of Life: A Poem of Life, Love and Death. (Bischoff, 31) Munch retrospectively assembled the series from paintings he produced during the 1890s. Many of the paintings in the series and that I cite can be seen at the Munch Museum website, The National Museum (Oslo) website, and in Wendy Gray’s May 17, 2018 article about this series in the Daily Art Magazine.

Munch visualized his subjects’ souls by portraying feelings and emotions through his paintings. The paintings invite—demand—that the viewer go beyond aesthetic appreciation and confront the soul of the subject. He takes viewers past the basic descriptive elements, like color and lighting, and right to feelings and emotions. Munch’s interest in this series arose from the sickness and death surrounding him most of his life, especially during his younger years: “I lead my life in the company of the dead―my mother, my sister, my grandfather and my father―with him above all―All my memories, the smallest of details, return to me…” (qtd in Bischoff, 34)

In The Sick Child (Munch’s sister who died of TB), the viewer observes and immediately feels the distraught look of the child’s aunt (the child’s mother had died of TB before), and also feels the child’s concern for her aunt. The countenance and body positions Munch depicts in the subjects of Death in The Sickroom (probably also about the death of Munch’s sister) amplify the viewers’ feelings through the compound effects of seeing clearly the abject despair of each subject at once.

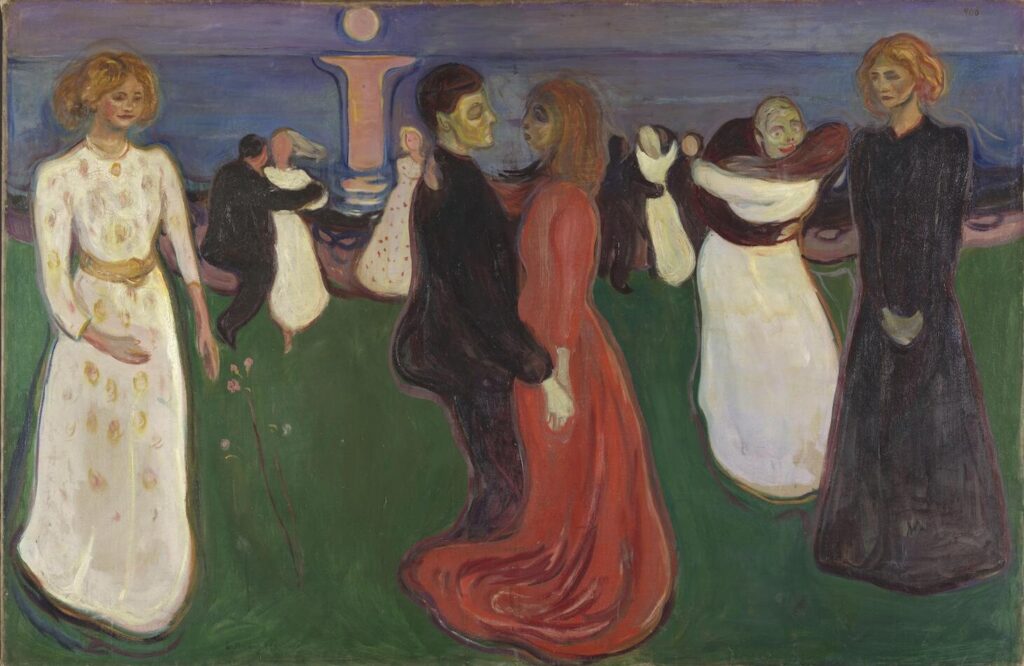

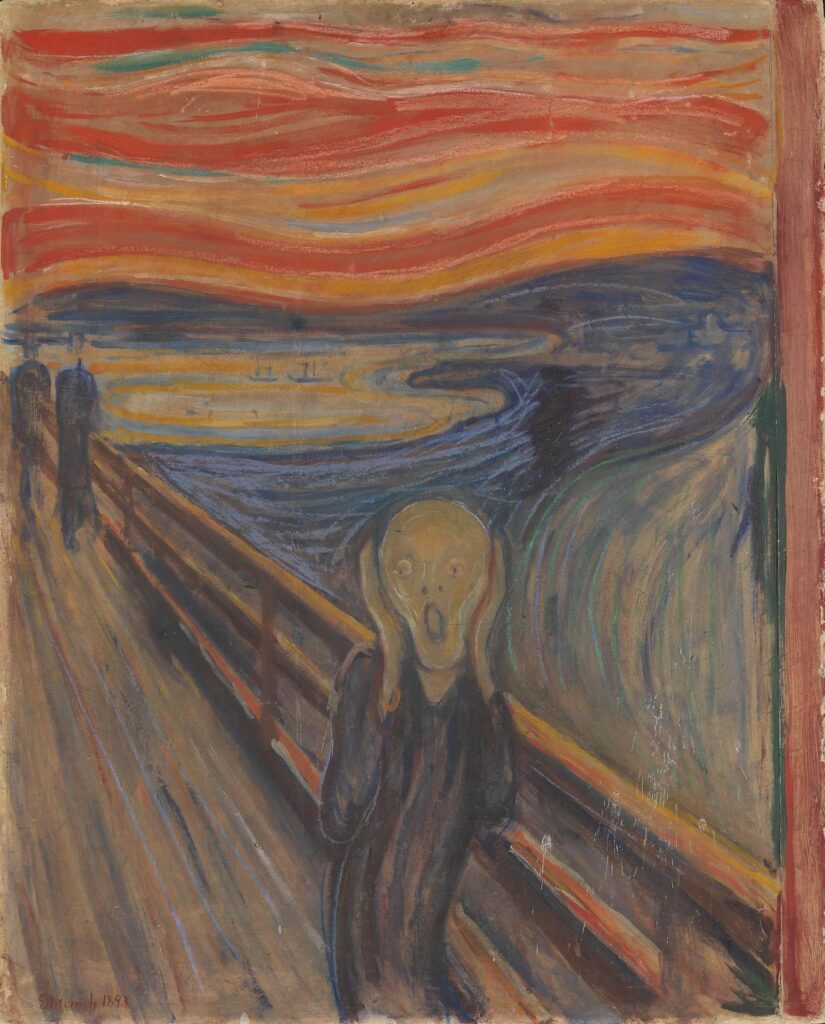

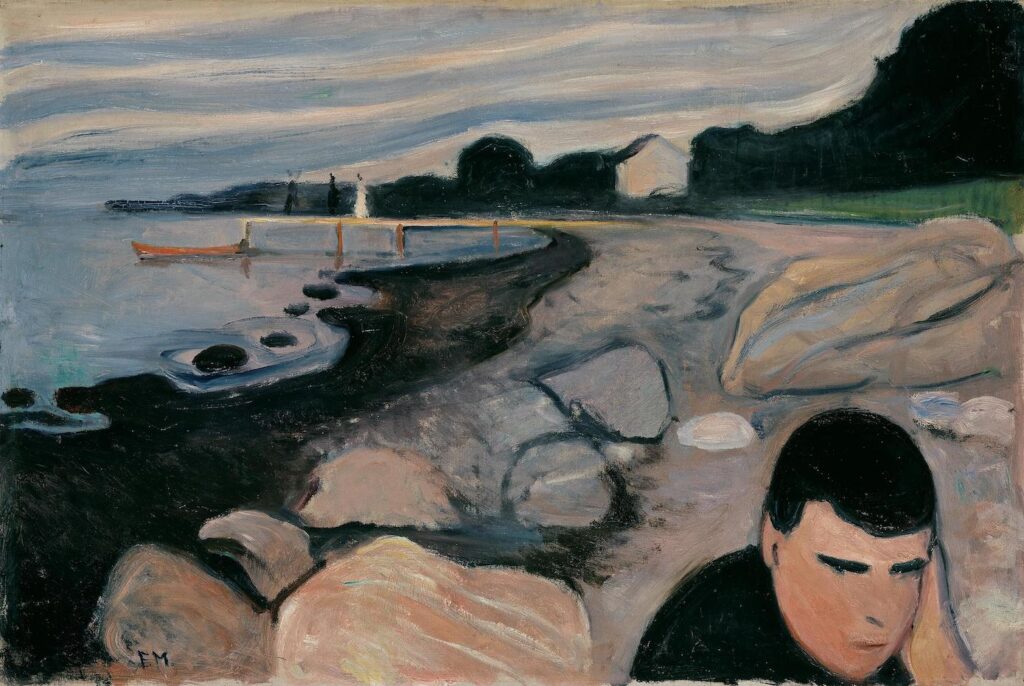

Munch leaves no doubt that the soul has its own standing as animated by the artist in his work. For example, in The Dance of Life, Munch describes how the soul can produce a range of feelings and emotions by showing himself dancing with his “first love” while being watched by someone who is joyful and someone else who is despondent. As another example, he extends the depiction of feelings and emotions beyond the human form to whirling skies, landscapes, and colors in The Scream, Anxiety, and Melancholy, which all display emotional chaos churning within the souls of its subjects.

From Munch’s The Friese of Life paintings, viewers feel empathy for the subjects before they appreciate the art itself. Munch makes this happen by connecting the soul of the artist to the soul of the viewer.

References

Bischoff, Ulrich. Edvard Munch. London: Taschen, 2000.

Gray, Wendy. Edvard Munch and The Frieze of Life. Daily Art Magazine, May 17, 2018, https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/edvard-munch-and-the-frieze-of-life/. Accessed June 3, 2021.

Works of the Frieze of Life. Munch Museum, https://munch.emuseum.com/collections/41719/livsfrisemotiver/objects. Accessed June 3, 2021.

Image Release Information

Title image: Self-Portrait in Hell

Edvard Munch

1903

Oil on canvas

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Sick Child:

Edvard Munch

1907

Oil on canvas

Tate Modern, London

Tate, London

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Death in the Sickroom:

Edvard Munch

1893

Tempera and grease pencil on canvas

National Museum, Oslo

Photo: Børre Høstland

Photo license: Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY)

The Dance of Life:

Edvard Munch

1899-1900

Oil on canvas

National Museum, Oslo

Photo: Børre Høstland

Photo license: Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY)

The Scream:

Edvard Munch

1893

Tempera and grease pin on cardboard

National Museum, Oslo

Photo credit: Børre Høstland

Photo license: Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY)

Anxiety:

Edvard Munch

1894

Oil(?) on canvas

Munch Museum, Oslo

Credit: Photo © Munchmuseet

Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY 4)

Melancholy:

Edvard Munch

1892

Oil on canvas

National Museum, Oslo

Photo credit: Børre Høstland/Jacques Lathion

Photo license: Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY)

A version of this post is also at the NYU LitMed Magazine.