Tourette syndrome is commonly associated with people who suddenly and unexpectedly voice profanities. While such occurrences are a part of the syndrome, they are neither prominent nor frequent features. Tourette syndrome produces a range of physical and verbal tics and behaviors attributed to both neurological and psychiatric causes.

Here I compare biomedical and literary text describing Tourette syndrome. The biomedical text from a neurology journal describes the characteristic tics and behaviors while the literary text from a Jonathan Lethem novel more vividly describes signs and symptoms, and describes how Tourette syndrome can affect lives.

The Biomedical

From: Alexander Kleimaker et al., Gilles de la Tourette Syndrome—A Disorder of Action-Perception Integration. Frontiers in Neurology, 2020; Volume 11 (November): Article 597898

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GTS) is a childhood-onset multifaceted neuropsychiatric disorder defined by several motor and at least one phonic tic, lasting for no <1 year. First symptoms usually occur as motor tics around the age of 6, commonly affecting the face, head and neck. In most cases, first phonic tics occur several years later. Importantly, GTS is characterized by a repertoire of repetitive tics, which is relatively stable at a given time but fluctuates considerably over longer time periods. Tics range from simple movement/sounds like eye blinking or rolling, sniffing, throat clearing or grunting to complex movements/vocalizations including squatting, head and body turning or twisting, utterances of words or, in rare cases, phrases, which can be obscene. Tics are sometimes difficult to distinguish from spontaneous movements in healthy controls. However, tics occur in a repetitive pattern and appear temporally and situationally misplaced.

pp. 1-2

Besides tics, sensory phenomena, particularly premonitory urges, represent a core feature of GTS. These sensations typically precede tics. Their characteristics are very diverse. In addition to the feeling of an urge to perform a certain action, of anxiety or restlessness also more localized somatic sensations including an itch, tinge, ache or numbness can occur. The execution of tics typically leads to a temporary decrease of premonitory urges, whereas their suppression causes an increase. Furthermore, echophenomena, i.e., automatic imitation of observed words (echolalia) or actions (echopraxia) as well as coprophenomena, i.e., the execution of obscene gestures (copropraxia) or, as pointed out above, the utterance of swearwords (coprolalia) are characteristic features.

The Literary

From: Jonathan Lethem, Motherless Brooklyn, New York; Vintage Contemporaries, 2000

In this novel, which I cover more broadly here, Jonathan Lethem offers a view of how Tourette syndrome can affect everyday life and how it can progress; how people with the syndrome can think about it; the balance people seek between benefits and side effects of drug therapies; and whether it’s acceptable to think that some verbal and physical tics are funny. In different parts of the novel, he also describes how Tourette syndrome reveals itself—its clinical presentation—to those who have it or are around someone who does.

Below are selected excerpts in which Lethem’s character, Lionel Essrog, describes his Tourette syndrome.

Context is everything. Dress me up and see. I’m a carnival barker, an auctioneer, a downtown performance artist, a speaker in tongues, a senator drunk on filibuster. I’ve got Tourette’s. My mouth won’t quit, though mostly I whisper or subvocalize like I’m reading aloud, my Adam’s apple bobbing, jaw muscle beating like a miniature heart under my cheek, the noise suppressed, the words escaping silently, mere ghosts of themselves, husks empty of breath and tone. In this diminished form the words rush out of the cornucopia of my brain to course over the surface of the world, tickling reality like fingers on piano keys. Caressing, nudging. They’re an invisible army on a peacekeeping mission, a peaceable horde. They mean no harm. They placate, interpret, massage. Everywhere they’re smoothing down imperfections, putting hairs in place, putting ducks in a row, replacing divots. Counting and polishing the silver. Patting old ladies gently on the behind, eliciting a giggle. Only—here’s the rub—when they find too much perfection, when the surface is already buffed smooth, the ducks already orderly, the old ladies complacent, then my little army rebels, breaks into the stores. Reality needs a prick here and there, the carpet needs a flaw. My words begin plucking at threads nervously, seeking purchase, a weak point, a vulnerable ear. That’s when it comes, the urge to shout in the church, the nursery, the crowded movie house. It’s an itch at first. Inconsequential. But that itch is soon a torrent behind a straining dam. Noah’s flood. That itch is my whole life. Here it comes now. Cover your ears. Build an ark.

pp. 1-2

‘Eat me!’ I scream.

This was an uncomfortable feature of Tourette’s—my brain would throw up ugly fantasies, glimpses of pain, disasters narrowly averted. It liked to flirt with such images, the way my twitchy fingers were drawn near the blades of a spinning fan.

p. 100

Have you noticed yet that I relate everything to my Tourette’s. Yup, you guessed it, it’s a tic. Counting is a symptom, but counting symptoms is also a symptom, a tic plus ultra. Thinking about ticking, my mind racing thoughts reaching to touch every possible symptom. Touching touching. Counting counting. Thinking thinking. Mentioning Tourette’s. It’s sort of like talking about telephones over the telephone, or mailing letters describing the location of various mailboxes.

p. 192

Insomnia is a variant of Tourette’s—the waking brain races, sampling the world after the world has turned away, touching it everywhere, refusing to settle, to join the collective nod. The insomniac brain is sort of conspiracy theorist as well, believing too much in its own paranoiac importance—as though if it were to blink, then doze, the world might be overrun by some encroaching calamity, which its obsessive musings are somehow fending off.

pp. 246-247

I’m tightly wound. I’m a loose cannon. Both—I’m a tightly wound loose cannon, a tight loose. My whole life exists in the space between those words, tight, loose, and there isn’t any space there—they should be one word, tightloose. I’m an air bag in a dashboard, packed up layer upon layer in readiness for that moment when I get to explode, expand all over you, fill every available space. Unlike an airbag, though, I’m repacked the moment I’ve exploded, am tensed and ready again to explode—like some safety-film footage cut into a loop, all I do is compress and release, over and over, never saving or satisfying anyone, least myself.

pp. 261-262

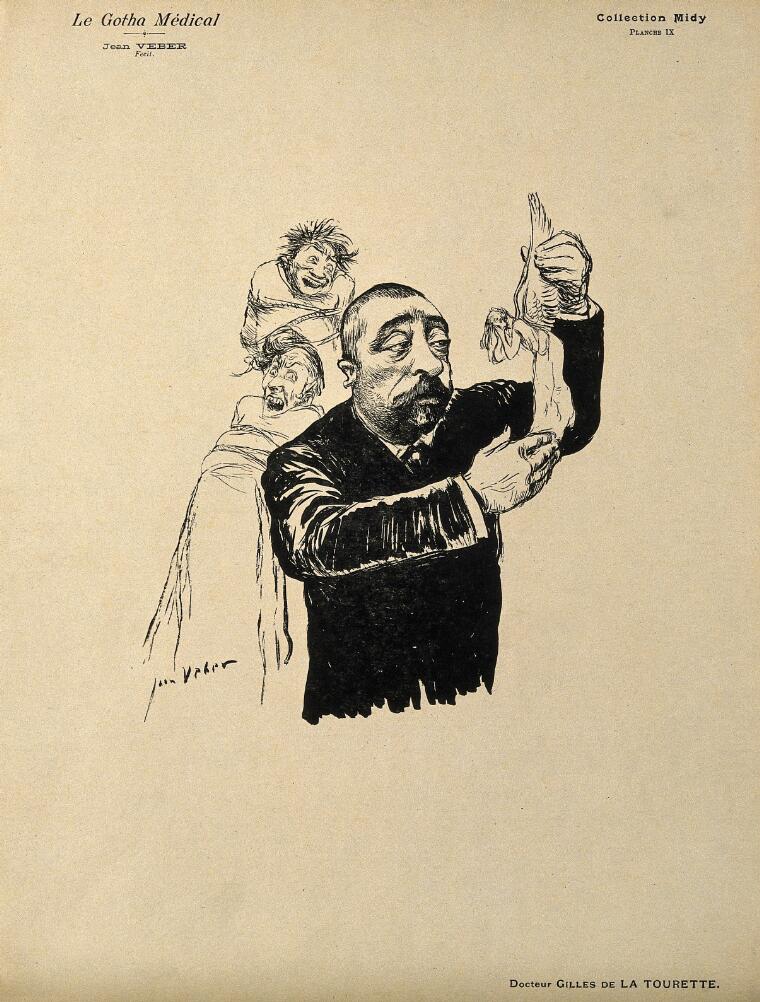

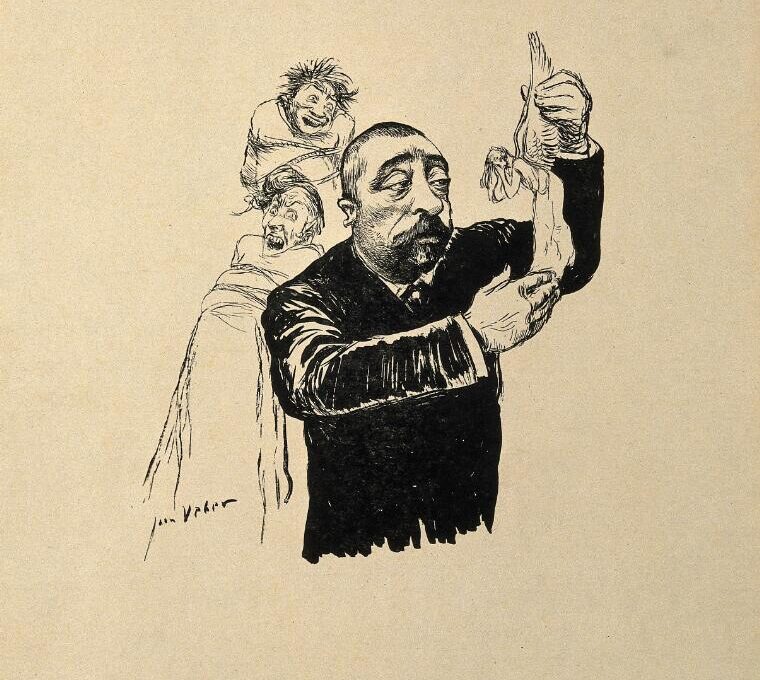

Title picture:

Georges Gilles de la Tourette

Reproduction of drawing by J. Veber

Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)