Rats, Lice and History

Hans Zinsser

Little Brown and Company

Boston

1935

301 pages

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic (Covid-19) has drawn me back to plague literature, both fiction (here, here, and here) and nonfiction (here, here, here, and here). Living during the pandemic lets us compare how people and societies are reacting now with how people and societies reacted to past epidemics in reported and imagined accounts. Judging from this literature, which is vast, not much has changed over the millennia and into the current, worldwide, infectious conflagration.

A Book Like Few Others

One book I wanted to read is Rats, Lice and History, written by Hans Zinsser (1878–1940) and published in 1935. I read it fifteen years ago, and as much as I wanted to reread it for the history of plagues Zinsser covers, I wanted to read it, ironically, for the charm, eloquence, erudition, humility, and humor he provides. The book stands apart from all the rest.

Zinsser had his doubts about whether he could write this book and confesses as much in the first sentence of the preface: “These chapters—we hesitate to call so rambling a performance a book—were written at odd moments as a relaxation from studies of typhus fever in the laboratory and in the field.” (p. vii) He reiterates his doubt as he opens the first chapter: “This book, if it is ever written, and—if written—it finds a publisher, and—if published—anyone reads it, will be recognized with some difficulty as a biography.” (p. 1) It was written, it was published, it was read, it made the 1935 New York Times bestseller list, and it was reprinted seventy-five times.

The book is a “biography,” Zinsser insists, because studying infectious diseases as they existed all over the world and across many centuries makes them “biological individuals.” (p. vii) He writes primarily for the “lay reader,” and “for our own amusement.” Motivating him was his “interest to impress the fact that we are dealing with a phase of man’s history on earth which has received too little attention from poets, artist, and historians,” (p. 9) Zinsser was an accomplished physician and scientist who attended elite schools and trained at prestigious institutions. Infectious disease was his beat and typhus was his interest.

As a biographer of typhus, Zinsser viewed his role as “setting forth the character and habits of the subject.” He distinguishes his role from that of medical historians, who instead “describe, chronologically and geographically, the almost uninterrupted succession of typhus epidemics which spared no byway and corner of Europe throughout the eighteenth and a large part of the nineteenth century.” (p. 282) Zinsser apologizes for refusing to make his biography a “playground for the dilettante of psychoanalysis,” which in his view was what biographies had become at the time. (p. 4)

Zinsser presses ahead with “careless confidence” (p. 16) until a Socratic interlocutor (a professional writer-friend) challenges him: “How can such a person, who is not quite a scientist and nothing of an artist, presume to undertake a task which no one not an artist could successfully accomplish?” (p. 17) Their dialog interrogates the difference between art and science to ascertain whether Zinsser can produce a credible biography of typhus. The “literary gentleman” asserts: “Biography is a job for an artist.” Zinsser resists: “Is a man to be denied an intelligent appreciation of art just because he knows something about a science? Is literature to be appraised only by those who have time to read after breakfast?” (p. 18) Eventually, Zinsser announces: “I’ve decided that it’s perfectly safe for me to go ahead with my biography of typhus” (p. 32). And so he did, as much as for any other reason, to “protest against the American attitude which tends to insist that a specialist should have no interests beyond his chosen field—unless it be golf, fishing, or contract bridge.” (p. ix)

The Preliminaries

Zinsser’s friend needn’t have worried because Zinsser is an eloquent writer, though wildly discursive in this book. He fills the first eleven of sixteen chapters—three-quarters of the pages—with an array of digressions and musings related and unrelated to typhus.

Among Zinsser’s preliminary musings are questions about whether distinctions can be made between art and science. He insists the two overlap, “where art is scientific and science artistic,” and says the difference may only be a matter of whether interpreting an observation “calls upon perception by the reasons or by the emotions.” Zinsser makes a finer point noting people in the arts such as DaVinci, Shakespeare, and Dostoyevsky observe “human experience,” and people in the sciences such as Newton and Pascal observe the “extended world.” (p. 22) Zinsser goes deeper still, but not without conceding the “subject has nothing to do with typhus fever.” (p. 15)

Zinsser makes us wonder, though, if it matters whether art and science are basically similar undertakings in their search for truth when he suggests humans are not up to the task through either. “The more our ingenuity reveals the orderliness of the nature about us and within us, the greater grows our awe and wonder at the majestic new achievement of art or of science, but which—in ultimate causes or in goal—eludes us.” (p. 35) He perseveres nevertheless considering many other topics in the first eleven chapters, most being connected to typhus and epidemics.

One theme Zinsser develops is the history of plagues, and how throughout history plagues were either rampaging or threatening some area of the globe. Another is how plagues have affected history. He puts a particular emphasis on how infectious epidemics had more to do with invaders winning wars and overthrowing dynasties than did their strategies or arms. He makes efforts to associate particular infectious agents as causes for some historic events (e.g., fall of Rome, Napoleon’s defeat in Russia).

Other themes Zinsser follows are more epidemiological. He notes the mysteries inherent in the natural history of many epidemics. How, after sickening and killing millions of people over hundreds of years, did some plagues just disappear, like leprosy, bubonic plague, the London sweat sickness, and many others? He impresses upon us, as many epidemiologists still do, that microbes causing epidemics and pandemics encircle us, and the right changes to our surrounding conditions (e.g., sanitation) and circumstances (e.g., crowding) can spark or extinguish infectious eruptions.

“We are at Last Arriving at the Point at Which We Can Approach the Subject of this Biography”

Zinsser finally gets to the putative subject of his biography, but not before he expresses worry that “discursiveness has been the ruination of this book up to the present time. (p. 214) He explains how he often strayed course when trying to find when typhus was first described.

The search turned up so many side issues and suggested so much that it amused us to discuss that we wandered from one digression to the next, following our own inquisitive nose and completely forgetting the reader, who, after all, was led—by our introductory chapter—to assume that he was about to read of typhus fever. Apologetically, therefore, and not without some astonishment, we discover that most of our book has run out of the pen, and the purpose for which it was undertaken remains unaccomplished.

p. 212

Having apologized for his wanderings, Zinsser promises readers they will not be “forced into further explanatory digressions.” He then starts his biography in earnest with “the birth, childhood, and adolescence of typhus.” (p. 229) While he mostly demonstrates discipline, he could not resist digressing entirely.

After all his analysis, Zinsser laments how epidemics will persist until conditions and circumstances favorable to outbreaks change, and he bemoans how little effort is put towards hygiene for this reason. “Even a superficial view of the evolution of human cleanliness…reveals that its development has lagged far behind the intellectual, aesthetic, and moral progress of man.” More damning yet, “elegance of manners and dress was never more assiduously cultivated, but cleanliness did not keep pace.” (p. 283-284)

What to do with this Book

More updated sources are available than this book for the history, epidemiology, and microbiology of typhus and epidemics, though, to be sure, it offers worthwhile findings and perspectives. Of perhaps greater value is the break Zinsser offers readers from the often turgid, abstract, and unintelligible prose typical of current biomedical, epidemiological, and historical academic literature. It’s possible: “We were not impelled…by a desire to be humorous, but rather by nature of our own subject.” (p. 235) He’s humorous. About his worries he leads readers astray from the purpose of his book from time to time, apology accepted.

The history Zinsser covers would be enough to get the book noticed in medical humanities circles, but his digressions on the common pursuits and aspirations of art and science should place the book in the medical humanities canon. Indeed, he precedes by decades others better known on the topic such as C.P. Snow, Jacob Bronowski, and E.O. Wilson among others. Thus, the book can serve people interested in the relationship of art and science, even if they are not drawn to a biography of typhus.

Or, the book can just be a source of enjoyment as it was apparently for Zinsser, who said in summing up his effort: “we have written along as it has suited our fancy, and have been amused and rested in so doing.” (p. ix)

Also

More background information about Hans Zinsser is available here.

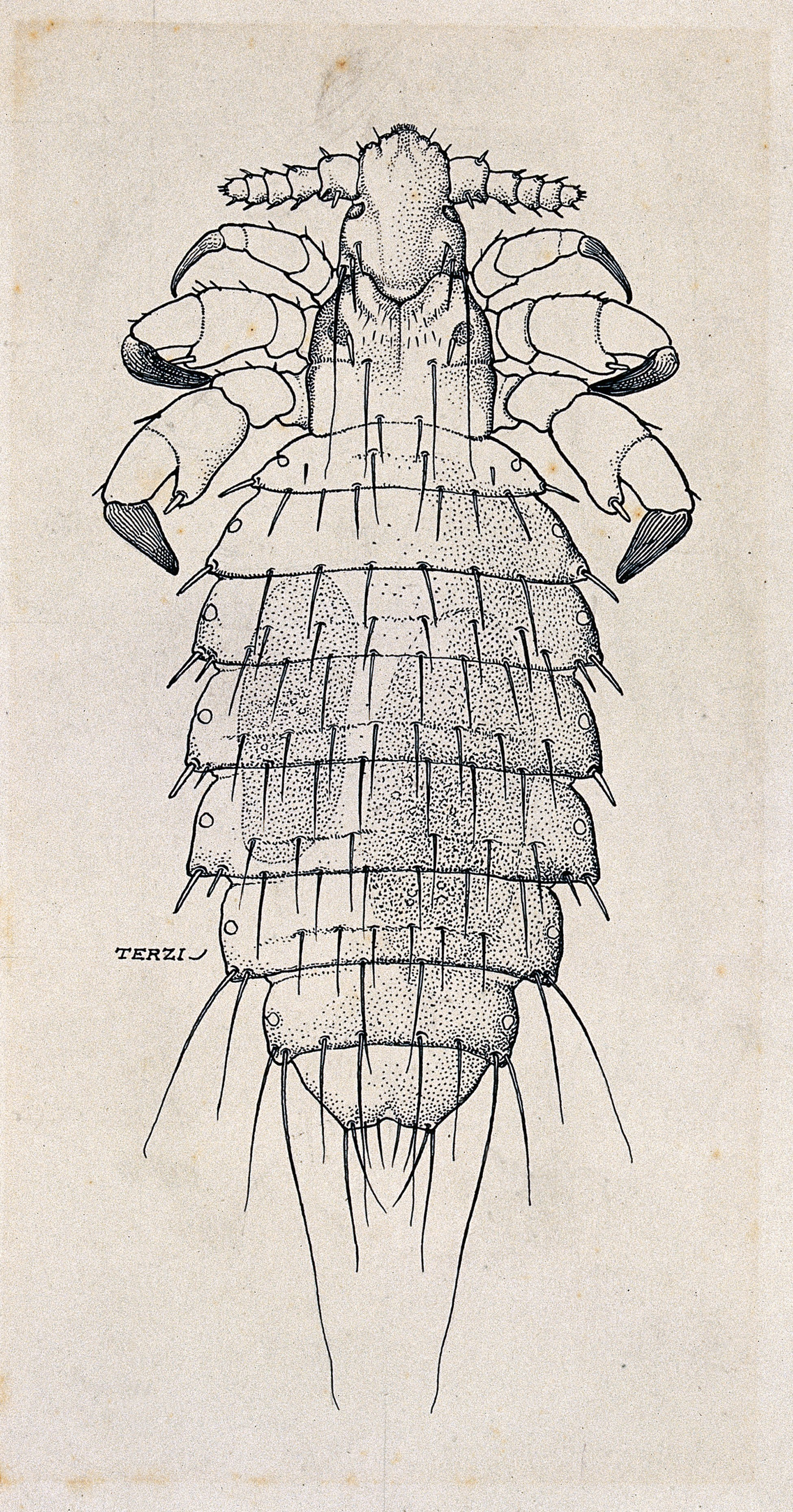

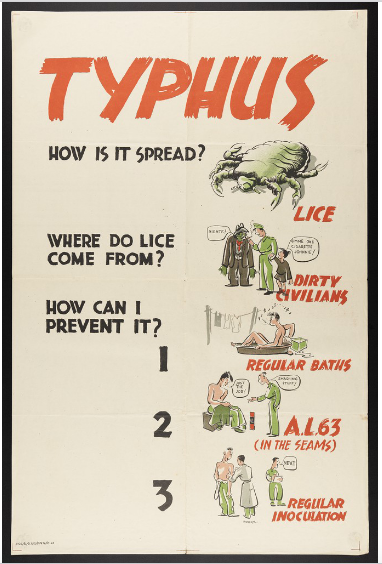

Title picture: A type of louse (Polyplax spinulosa)

Pen and ink drawing by A.J.E. Terzi, ca. 1919.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)