According to the art:

In this film death from late-stage cancer is considered as a battle to be waged or as a fate to be accepted through grace, and how different punctuation in the last line of John Donne’s poem, Death Be Not Proud, can help to make this distinction.

The Movie:

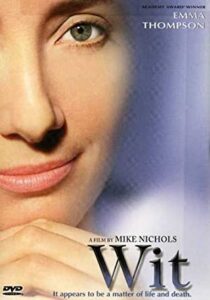

The film Wit is an adaptation of Margaret Edson’s play of the same name. The storyline follows the main character, English Professor Vivian Bearing, through the treatment she receives for her late-stage ovarian cancer. The story is set during the waning years of the twentieth-century and the action takes place mostly in a teaching and research hospital. Edson brought her observations from working on AIDS and cancer treatment units during the mid-1980s to the story. The play won Edson the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. The film adaptation was released two years later, and eventually found its way into the medical humanities canon.

The promotional quotes on a DVD package for the film invites a casual viewing when it says, “Fractures the funny bone, then the heart.” Without much effort, however, the viewer of this film could come away thinking it is merely a commentary on the state of physician – patient relationships. Some benefit is to be gained from this view, to be sure. But, a deeper engagement with Wit is revealing and rewarding on how to think about a battle against death versus the grace of accepting death.

The promotional quotes on a DVD package for the film invites a casual viewing when it says, “Fractures the funny bone, then the heart.” Without much effort, however, the viewer of this film could come away thinking it is merely a commentary on the state of physician – patient relationships. Some benefit is to be gained from this view, to be sure. But, a deeper engagement with Wit is revealing and rewarding on how to think about a battle against death versus the grace of accepting death.

The Metaphorical and the Metaphysical:

Edson says her play is about, “death, grace and redemption.” (Martini 24) In their film adaptation, Mike Nichols and Emma Thompson chose to place an emphasis on death and grace, giving redemption much less attention. (Sykes) Both the play and the film use metaphorical comparisons between Bearing’s treatment and John Donne’s metaphysical poetry to distinguish death as a pitched battle from death as a moment of grace. The Donne poem Edson uses is, Death, Be Not Proud.

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; For those whom thou think'st thou dost overthrow Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul's delivery. Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell, And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well And better than thy stroke; why swell'st thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

Upon learning of her diagnosis of advanced, ovarian cancer, Bearing is given a choice of experimental and highly toxic chemotherapy, or measures to make her as comfortable as possible as the disease takes its course. She chooses the experimental treatment. The film shows in vivid detail the violence visited on her during treatment, over and over again, and before she can die.

In choosing Donne’s poem as a metaphor for Bearing’s choice, death in battle or death in grace, Edson draws from only the last line, and specifically on two versions of it based on punctuation differences. As presented in the film, how the last line in Donne’s poem is punctuated by different publishers with either a comma or a semi-colon between “And death shall be no more” and “Death, thou shalt die,” can lead to an understanding of death as an event characterized by grace or as the failure to win a battle against fate, respectively.

The explanation in the film is presented in a flashback to when Bearing is a college student and when her mentor, Professor E. M. Ashford, impresses upon her the difference between these two versions. With the semi-colon (an “insuperable barrier”), the battle is on and puts death on stage: “And Death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.” With the comma (“nothing but a breath”), a “simple meaning” yields a grace that flows from the continuum of “life, death, and life everlasting”: “And death shall be no more, Death thou shalt die.”

Pedro de Villegas Marmolejo / Public domain

The film endeavors to also show the different interpretations of the punctuation by juxtaposing scene framings with scene actions. The juxtaposition is never far from the viewer’s eye. A copy of the painting of Saint Sebastian that is prominently featured on the wall where Professor Ashford is making her forceful distinction between the two interpretations is also seen on the table next to Bearing’s hospital bed (a semi-colon). On the walls of the hospital room where the viewer witnesses Bearing wretch from chemotherapy are two pictures showing the beauty and subtlety of day easing into night (a comma). Bearing’s encounters with the medical oncology team are shown to be severe, fast-paced, chaotic, “hysterical,” and sometimes preceded by jarring and foreboding music (a semi-colon). In contrast, Bearing’s encounters with kindness and grace are simple, slow-paced, and sometimes accompanied by soothing music (a comma).

At the end of the film, Bearing is shown transitioning to an understanding of death that is closer to Professor Ashworth’s lesson through a conversation with Susie, her nurse. In a simple and intimate scene suffused with grace, Bearing first admits to being unsure of her thinking on her plight and then ultimately rejecting resuscitation (a semi-colon) for a quiet passage (a comma).

Works Cited:

Donne, John. Death, Be Not Proud. Poetry Foundation. Accessed September 29, 2020.

Nichols, Mike and Thompson, Emma. “Wit.” (DVD) HBO Home Video, 2001.

Martini, Adrienne. “The Playwright in Spite of Herself.” American Theater. October (1999): 22-25.

Sykes, John D Jr. “Wit, Pride, and the Resurrection: Margaret Edison’s Play and John Donne’s Poetry.” Renascence 55. 2 (2003): 163-75.

Note on title picture:

Credit: Saint Barbara comforting the dying. Line engraving, 17–. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

A dying woman is comforted by a priest. Death (a skeleton) holds a scythe and hourglass, Time (a winged man) points to a book. Above, Saint Barbara, with her attributes the crown and tower, holds the Eucharist. From her heart a ray of grace descends to the dying woman.

[Austria?] : [publisher not identified], [between 1700 and 1799?]

1 print : line engraving ; image and lettering 14.3 x 9 cm