Overview

Although illness can be distinguished from disease and sickness (see Distinguishing Illness from Disease and Sickness page), that distinction does not itself give us a lot of detail about the illness experience. Illness can be conceived in any number of ways, but illness as it presents in ways the humanities can address is the form of illness that is relevant to our project. Therefore, our endeavor will be aided from breaking down the illness experience into elements that can conform to basic forms of humanities works, and from showing how the Humanities can address illness in these forms in ways Biomedicine doesn’t or can’t.

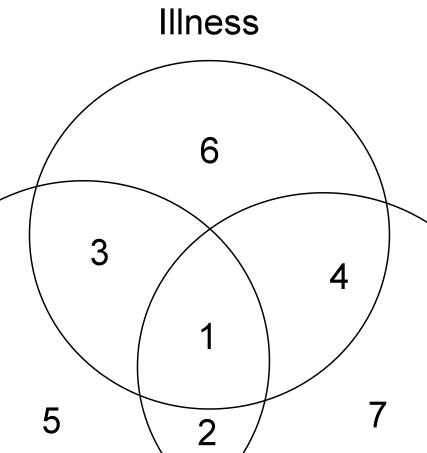

Peter Barritt proposes a workable set of elements of illness that fit this need, and they are as follows: illness as questions; illness as loss; illness as experience; and illness as change. Judy Segal adds illness as argumentation. These elements are not exhaustive, and nor are they mutually exclusive. These elements are explored in separate posts:

Illness as questions

Illness as loss

Illness as experience

Illness as change

Illness as argumentation

These elements of illness, i.e., illness as questions, illness as loss, illness as experience, illness as change, and illness as argumentation give us keener insights into what humanities works could address by providing more definition to the needs of people with chronic illness. Each of these elements, however, can be aggregated under an overarching concept of illness as suffering, which can also provide insights into the humanities content that could work for people with chronic illnesses.

Cassell offers a view of suffering that conforms to the personal illness experience: “suffering occurs when an impending destruction of the person is perceived; it continues until the threat of disintegration has passed or until the integrity of the person can be restored in some other manner.” This characterization of suffering puts the person with a health problem at the center of the illness experience. Furthermore, this suffering can originate from the meaning a person assigns to an illness experience. People generate meanings from their interpretations of the various elements of illness, such as from the questions generated, losses perceived, experiences lived, and changes required. Suffering results when these interpretations convey a threat of destruction or disintegration.

The meanings people derive from their health problems are thus, in turn, central to illness experiences and can become important to the selection of humanities works to associate with various chronic illnesses. Meanings that take shape from particular needs may further lead to the most relevant humanities works for people with chronic illnesses; therefore, breaking down meaning into needs can facilitate the objective of finding the most relevant humanities content. Drawing from the psychology literature, Cassell lists four particular needs that contribute to meaning: (1) the need for people to have a purpose, (2) the need for people to provide value, (3) the need for people to believe they can make a difference, and (4) the need for people to believe they have self worth. He further states: “Finding meaning…might have an important therapeutic impact on persons as they discover how much more there is for them, and how much more worth they have in view of what they find (or are helped to find) in the world,” and hence, some guidance toward finding humanities content that addresses these needs.

Beyond aiding us in seeing the needs of people with chronic illnesses, illness as suffering also helps us see better the banality of suffering when it occurs. We are surrounded by suffering, and so perhaps we become inured to it; life goes on, as described by W.H. Auden in his poem Musée des Beaux Arts:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the

torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns

away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

The banality of suffering may also stem from the absence of the right language to convey it. As Scarry said about pain, to experience pain directly is to know certainty, but to hear about someone’s pain is to have doubt; perhaps the same can be said about suffering. Therefore, a concentrated effort on the broader experience of suffering is required to address the needs of people with chronic illnesses because the absence of language makes it possible to miss them.

Illness, in these constituent forms as questions, loss, experience, change, and argument, and as a more general form of suffering is not adequately addressed by contemporary Biomedicine. This has not always been the case. Indeed, only if we mark the beginnings of contemporary Biomedicine to about two hundred years ago can we say that it never has accommodated illness. But, perhaps contemporary Biomedicine should not be expected to or maybe it cannot be expected to, at least by itself. Perhaps an integration of Biomedicine and Humanities is the solution.

Sources:

Peter Barritt, Humanity in Healthcare: The Heart and Soul of Medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2005.

Judy Z. Segal, “Illness as Argumentation: A Prolegomenon to the Rhetorical Study of Contestable Complaints,” Health11, no. 3 (2007): 228-238

Eric J. Cassell, The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine, 2nded. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Edward Mendelson, ed., The English Auden: Poems, Essays and Dramatic Writings. (London: Faber and Faber, 1977).

Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain(New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).