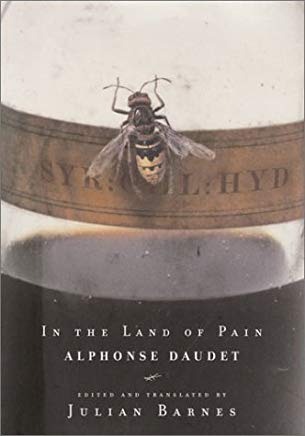

Alphonse Daudet

Julian Barnes (editor and translator)

Alfred A. Knopf

New York

2002

87 pages

According to the Art:

Alphonse Daudet was a nineteenth-century French writer whose syphilis progressed to the late stages involving devastating neuropsychiatric effects. The book comprises notes he made about his experiences with pain, unsteadiness and paralysis, what chronic pain and illness does to personal outlooks, isolation, and relationships, and the pleasures and pains of morphine.

Synopsis:

Alphonse Daudet was a well-known, French novelist, playwright, and journalist, who lived between the years 1840 and 1897. In the Land of Pain is a book he wrote about living with tabes dorsalis, which is the degeneration of nerve cells and fibers near the spinal cord. In Daudet’s case, as in most cases, tabes dorsalis results from a syphilis infection that has gone untreated for decades. With the disruption and loss of nerve cells and fibers in and around the spinal cord, people with this condition can experience severe pain, altered sensation, unsteady gait and loss of coordination (ataxia), loss of hearing and vision, difficulty with verbal expression (aphasia), and dementia.

The book takes the form of notes Daudet composed about his experiences with tabes dorsalis, and it is divided into two parts. The first part (The Elemental Truths – Pain) focuses on his pain and suffering, and the second part (In the Land of Pain) on his experiences at the “shower-baths” and “spas” where his physicians sent him for treatment.

Daudet experienced many of the clinical manifestations of tabes dorsalis described in biomedical texts as “incoordination, pain, anesthesia, and various visceral trophic abnormalities…, severe lightening pains…, loss of muscle stretch reflexes, and sensory loss…” and eventually “severe spastic paraparesis and autonomic dysfunction.” (cited below) As a literary figure, he relied on metaphors and allusions to create a picture of the actual experience. In particular, he addressed his experience with paralysis, numbness, and unsteadiness in his legs.

I feel like some creature from mythology, whose torso is locked in a box of wood or stone, gradually turning numb and then solid. As the paralysis spreads upwards, the sick man changes into a tree or a rock, like some nymph from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

p. 43

Can’t go down a staircase if there isn’t a handrail; can’t walk across a waxed floor. Sometimes I feel as if I don’t own part of myself – the lower half. My legs get confused.

p. 41

In describing his pain experience, akin to the biomedical description of “severe, lightening pains,” he refers to “‘the wasps,’ the stinging and stabbing here, there and everywhere.” (p. 31) He also gives thought to how pain works on its sufferers in certain ways, such as when he suggests in a note that the degree of pain felt does not directly correspond to the suffering it causes: “This pain of mine. It’s bearable, and yet I cannot bear it.” (p. 9) In another note, he asserts that pain turns sufferers into poor narrators of their own experiences because of the necessary reliance on memory of pain events.

Are words actually any use to describe what pain (or passion, for that matter) really feels like? Words only come when everything is over, when things have calmed down. They refer only to memory, and are either powerless or untruthful.

p. 15

Analysis:

In the edition I review here, Julian Barnes serves as editor and translator, and he contributes an introduction, a coda, and footnotes. Barnes places Daudet among the “literary syphilitics” of the time, who included Baudelaire, Flaubert, Maupassant, and Jules de Goncourt

As a series of notes, the book does not progress in any chronological order, and it does not aggregate particular experiences into sections. The notes appear to reflect what came to Daudet at a particular moment. Some of the notes are as brief as just a couple of words or a single sentence, or as long as a few paragraphs, and Barnes elaborates on some of them with footnotes. To Barnes, “Notes seem an appropriate form in which to deal with one’s dying. They imply the time, and the suffering, which elapses between each being made: here is a decade or so of torment reduced to fifty pages.” (p. xiv) Though the book is comprised of notes, they provide more than just a catalog of events with their insights on pain and illness beyond how they affect an individual’s life.

Some of Daudet’s notes address broader consequences of his predicament. He laments in one, for example, that “Pain is always new to the sufferer, but loses its originality for those around him. Everyone will get used to it except me.” (p. 19) He adds thoughts on the illness experience generally with a note about how a person with an illness is considered “a loner, someone isolated and lost amid the noise and turbulence of life, just a strange creature with a funny illness” (p. 73).

While Daudet experienced pain and thought about pain, he also sought relief from it. He needed relief at a time when morphine was available as was the means to inject it. He noted both the pleasures and pains of morphine. Of the pleasures, Daudet recounted how he “Spent three delightful hours there [the house of a morphine addict]. The injection wasn’t too shattering, and as always made me garrulous and took me out of myself.” (p. 8) Of the pains, he recounted the effects of trying to stop using morphine: “In bed. Dysentery. Two injections of morphine a day, about twenty degrees. No longer able to get out of the habit. My stomach has adapted itself a little: with five or six drops. I no longer vomit, although I can’t eat. Forced to continue to taking chloral.” (p. 31) And, “I’m trying to reduce my intake of morphine to one injection a day. It makes me jumpy, irritable and spiteful.” (p. 39)

The second part of the book from his time at spas is more gossipy and dyspeptic than insightful about illness experiences.

I loathed watching my neighbors eat.

p. 56

In the hotel courtyard, the to-and-fro of patients. A march-past of different diseases, each more dreadful than the previous one.

p. 60

Women, Sisters of Charity, nurses, Antigones.

p. 61

Russians, inscrutable Asiatics.

Priests.

Music: like a morphine injection.

Rages.

The Ambitious One, the ‘Napoleon Who Never Made It’, in the bath.

The crazies.

The chatterboxes.

They’re like this not just because they’re from the Midi, but because of nervous illness.

One of his notes in this part of the book, however, offers a view of how chronic illness can wear people down (and perhaps serves as an explanation for this orneriness).

I’ve passed the stage where illness brings an advantage, or helps you understand things; also the stage where it sours your life, puts a harshness in your voice, makes ever cogwheel shriek.

p. 65

Now there’s only a hard, stagnant, painful torpor, and an indifference to everything. Nada!…Nada!

Arthur Kleinman, in his book The Illness Narratives likened this phase of chronic illness to a “volcano: it does not go away. It menaces. It erupts. It is out of control. One damned thing follows another.” Daudet would have made note of Kleinman’s observation.

Also:

The source for the biomedical text on tabes dorsalis is an article by John Berger in the December, 2011 issue The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease (p. 913). The journal has been a source for medical information about the neurological manifestations of syphilis since it first started publishing in 1874.

How particular notes Daudet made concerning his experience with tabes dorsalis compares with current biomedical descriptions is isolated in a post here.