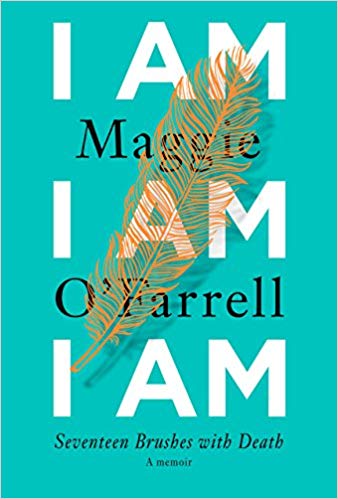

Maggie O’Farrell

Alfred A. Knopf

New York

2018

288 pages

According to the Art:

The book is a memoir based on seventeen near-death events involving the author, and in a few instances, her children. Though the events make for harrowing and interesting tales, they are written such that they also convey what it’s like to nearly die from different acute illnesses, accidents, violence, and bad judgment. Collectively, the stories show the availability of human resilience in the face of repeated threats to life.

Synopsis:

Maggie O’Farrell describes the book in a scene involving a casual conversation she had with her mother over tea.

As she lifts the pot to the table, she asks me what I’m working on at the moment, and, as I swallow my water, I tell her I’m trying to write a life, told only through near death experiences.

She is silent for a moment, readjusting cosy, milk jug, cup handles. ‘Is it your life?’ she asks.pp. 142-143

‘Yes,’ I say, a touch nervously. I have no idea how she’ll feel about this. ‘It’s not…it’s just…snatches of a life. A string of moments. Some chapters will be long. Others might be really short.’

This conversation is the only place in the book where O’Farrell describes her intentions in writing it. But, what O’Farrell describes to her mother is exactly what the book is, i.e., a memoir comprising seventeen “brushes with death,” as she calls these moments. There is no prologue, there are no interludes, there is no coda, just the seventeen stories.

Few people will experience any one of these events, and perhaps only O’Farrell has experienced all of the events she tells us about. She categorizes them based on the anatomy involved in a particular brush with death. For example, some of the chapter names are: “Lungs” (three times), “Neck” (twice), “Abdomen,” “Intestines,” “Cerebellum,” “Circulatory System,” “Whole Body.” The one exception is the chapter, “Daughter.”

Other ways of categorizing the near-death experiences O’Farrell covers could be based on whether they threatened O’Farrell herself or any of her children, whether they were the result of bad luck (e.g., illness) or bad judgment (e.g., near drowning), or whether the threat originated outside the body (e.g., accident) or within the body (e.g., illness, medical procedures). The brushes with death from outside the body involved violence (twice), decapitation (twice), drowning (three times), a plunging commercial airliner, and a knife throwing exhibition. From within her body, close calls involved encephalitis as a child, amoebic dysentery while traveling in a developing country, a Cesarean section gone awry, and a few missed miscarriages (i.e. when fetus dies but no signs or symptoms manifest and surgical procedures become necessary). A daughter was born with severe allergic conditions that caused the child misery pretty much all the time interspersed with episodes of life-threatening reactions. O’Farrell’s son was almost lost in one of her near drownings.

O’Farrell leaves it to the epigraph she placed at the beginning of the book to stitch together how these stories collectively reveal the possibility of the human spirit to get us through the most serious and persistent challenges to our being. For this epigraph, she takes a line from Sylvia Plath’s novel, The Bell Jar:

I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart.

I am, I am, I am.

Analysis:

O’Farrell’s stories about her close calls with death are harrowing enough to make for an interesting reading experience, good yarns all. They convey the fears, frights, and forebodings that came with them, as well as what she learned from some of them, and thus what we can learn from them. Her prose style is spare and brisk, but potent. We get a good sense for what it is like to experience the various types of predicaments she tells us about.

What it’s like to feel as if you are about to drown:

At this point, your lungs start to burn, your pulse races, your heart tripping into an allegretto time signature, aiming to alert you to the situation, as if you haven’t noticed that you are about to die. You have an urgent need to cough but you know you mustn’t, you cannot. Your thoughts are monosomic: It’s okay, it’s okay, it’s okay. and then: It’s not okay, It’s not okay, it’s not.

p. 31

What it’s like in the midst of a severe illness to think you may be nearing your end and you may think that’s okay, as was the case for O’Farrell during her episode of amoebic dysentery:

There is, I observe to myself, even through illness and pain, nothing left in my system. Nothing at all—no liquid, no food, no bile, even. I am utterly emptied out. My skin is scalding, desiccated. It hurt to move my eyes inside their parched sockets. But, still, I don’t want to go to the hospital. I want only to be alone.

p. 161

What it’s like to function with persistent effects of illnesses, like the neurologic sequelae of O’Farrell’s bout with encephalitis as a child:

The illness comes in and out of focus for me, in adulthood. I can go for days without thinking about it; at other times it feels like a defining event. It means nothing, it means everything…It means that my perception of the world is altered, unstable. I see things that aren’t there: lights, flashes, spots or rents in the fabric of vision. Some days, holes will crackle and burn in the centre of whatever I look at, and text disappears the minute I turn my gaze upon it.

p. 234

What it’s like to realize all that is lost with a miscarriage:

You sense its corporeality disintegrating, becoming mist. Gone is the child with blond or dark or auburn hair; gone is the person they might have been, the children they themselves might have had. Gone is that particular coded mix of your and your husband’s genes.…Gone are your plans for and expectation of the next year of your life. Instead of a baby, there will be no baby.

pp. 102-103

What it’s like to worry day after day after day that your child will experience another life-threatening allergic reaction:

You will go to bed at night and breathe into the dark and think, one more day. I kept her alive for one more day.

p. 283

What it’s like to be in a developing country seeking acute care in a hospital clinic and you are taken care of first only because you have American dollars as was the case when O’Farrell’s travel mate sought immediate attention for her:

Through the door and we are confronted with a scene from Dickensian London, from a First World War film, from a nightmare. The foyer of the hospital is filled with people, literally filled. There isn’t a chair, a square foot of floor or wall space that isn’t taken up by a human form…People sit, lined up, along the reception desk; others lie on mats or flattened cardboard boxes on the floor, asleep or just moaning lightly to themselves. Children, cradled in the arms of adults, wail.

pp. 167-168

A man in a white coat picks his way through the crowd and stops in front of us. He puts a weary hand to my forehead, he pulls up my lips, as if I am a horse, and examines my teeth.

“Stomach?” he says to Anton, in English.

Anton nods.

“You pay?” he asks

“Yes.”

“Dollars?”

Anton digs in my money belt and shows the doctor a wad of my emergency-only American dollars.

The doctor nods, takes me by the arm, leads me through the maze of people.

O’Farrell’s brushes with death occurred when she was between the ages of three and thirty-eight, with the exception of the serious problems her daughter faces, which are ongoing. O’Farrell was forty-six-years-old at the time this book was published, so we can expect a sequel in all likelihood, as horrifying a prospect that should be to her. Or, if not from O’Farrell, perhaps from her daughter who has survived many life-threatening events from her allergic reactions, and as described by her mother, “she is, she is, she is.”

Also:

A version of this review is posted on the NYU Literature, Medicine and Arts Database.